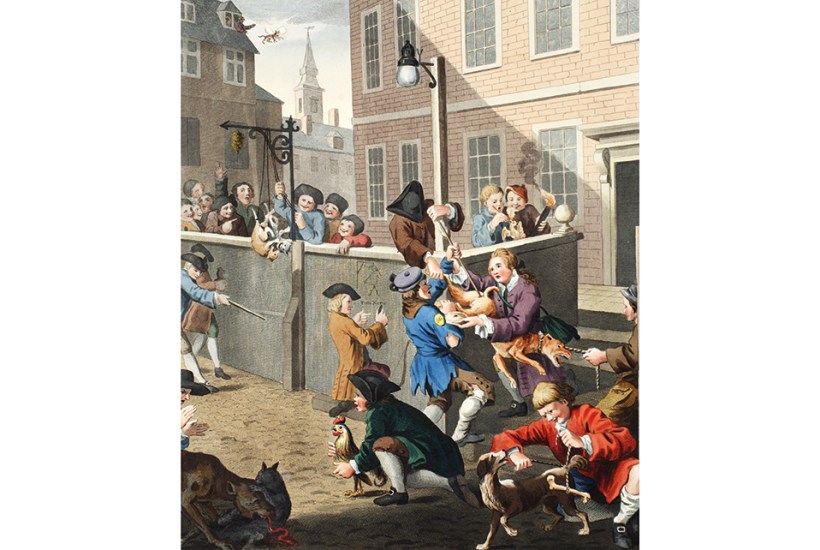

To come across dates and names carved into a choirstall or ancient tree is to experience a momentary frisson, a startled connection with the past. Yet this practice of making ‘unauthorised’ personal graphic statements in public spaces is often thought of as antisocial, something to be erased immediately. Unless of course they are by Banksy, whose spray-painted outpourings cost local councils a great deal to clean off before they came to be regarded as valid documents, articulating the thoughts and imaginings of the disaffected.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in