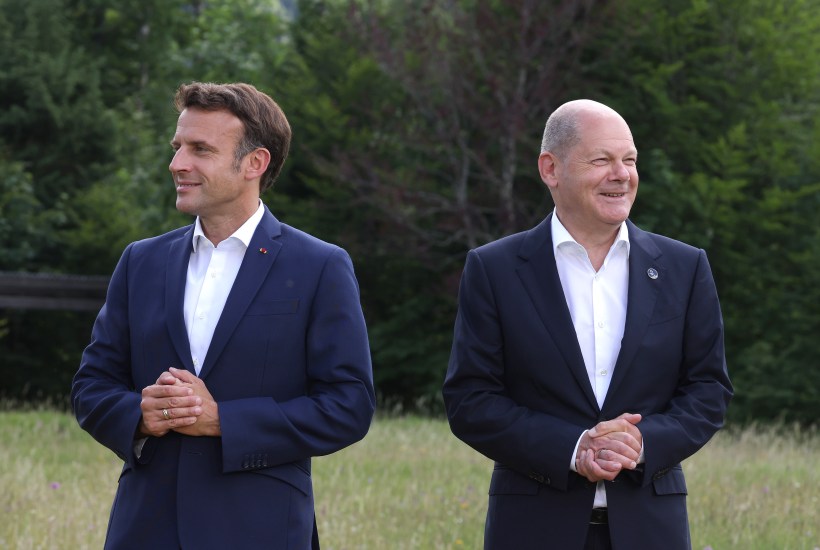

There was a time earlier this century when few politicians in France would dare criticise Germany. The country was the powerhouse of Europe and Angela Merkel was the de facto president of the continent. Today there is political mileage to be had in attacking Germany, and the assaults have increased this year as campaigning intensifies ahead of June’s European elections.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in