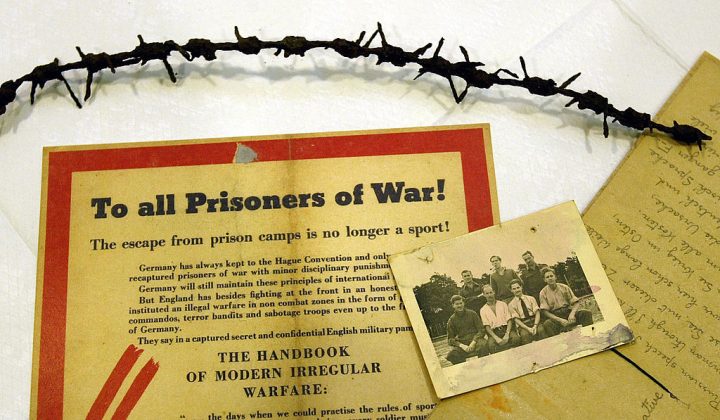

Anyone for whom a screening of the film The Great Escape is an annual Christmas tradition will know how strong a hold the myth of that escapade holds over the collective British imagination. But a myth is all it is. The old 1960s movie, with its star-studded cast performing stiff upper lip heroics, manages to turn a horrific tragedy and crime into an ‘Allo Allo’ style farce akin to Carry On Tunneling.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in