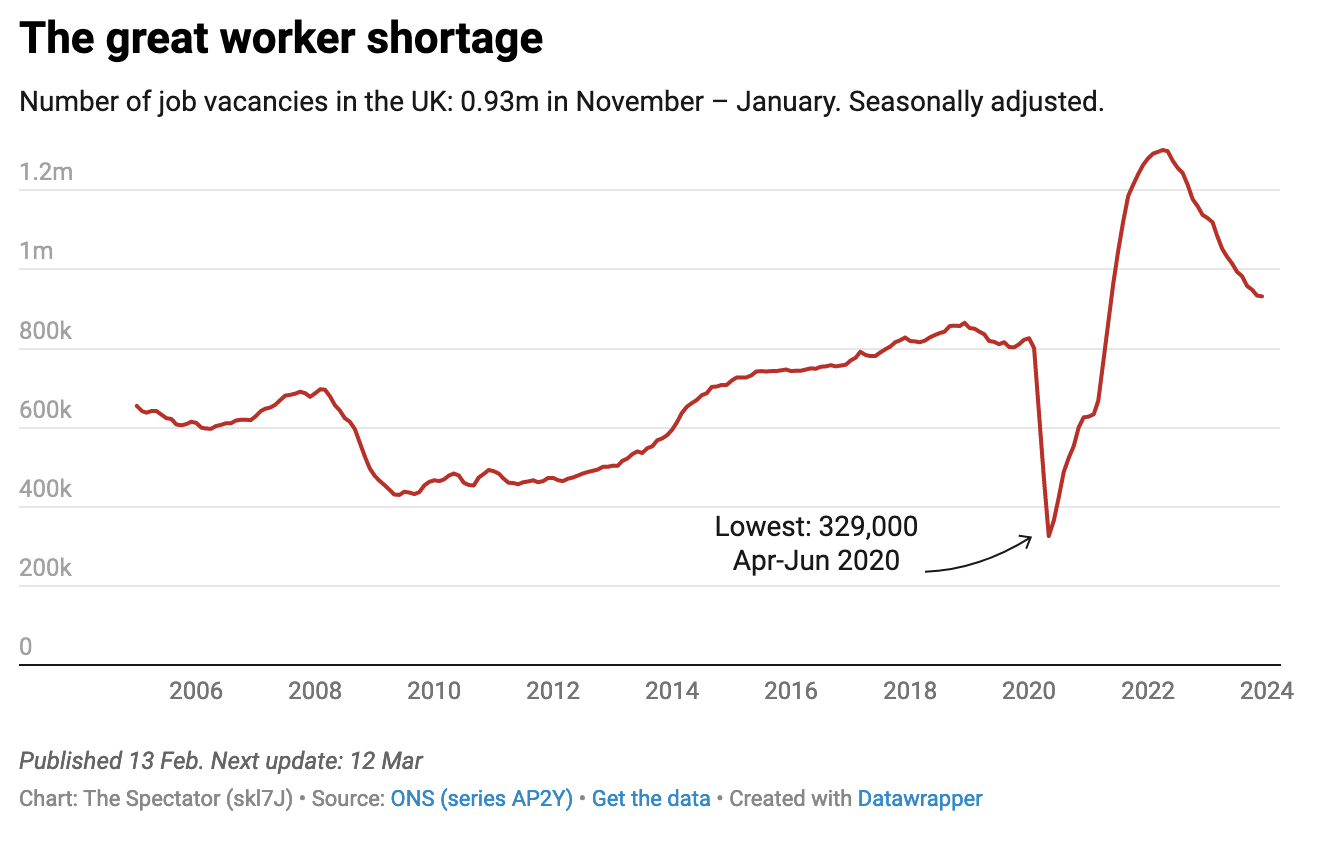

Has the Labour market cooled down enough for the Bank of England to change its mind on interest rates? Almost certainly not, based on the latest data from the Office for National Statistics, out this morning. The reintroduction of the Labour Force Survey data, which had to be suspended temporarily due to poor and limited feedback, has now been reinstated, showing fewer changes in the labour market than experts were hoping to see.

Job vacancies fell for the nineteenth consecutive time – but not by much.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in