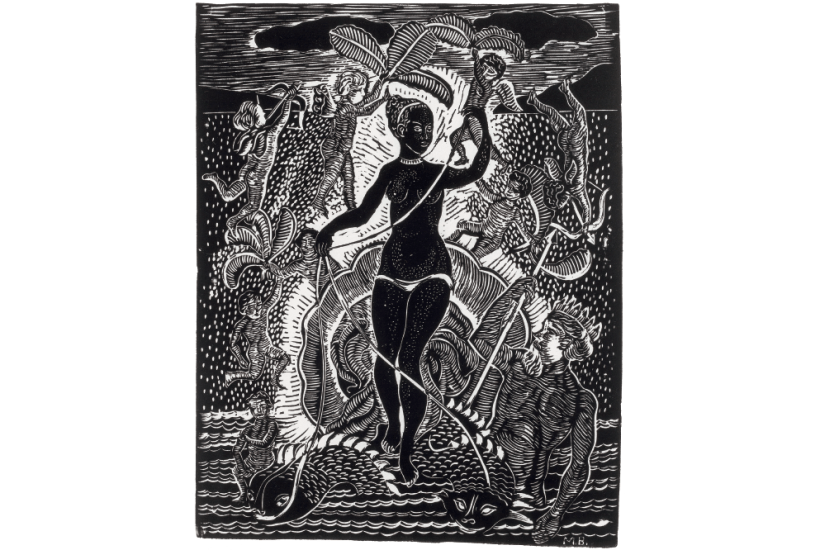

In the wake of the Fitzwilliam Museum’s exhibition Black Atlantic about its founder’s ties to the slave trade comes the Royal Academy’s Entangled Pasts, less of a mea culpa than an examination of conscience by an institution which, although hailed by its first president Sir Joshua Reynolds as an ‘ornament’ of Empire, was innocent of direct links to slavery.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in