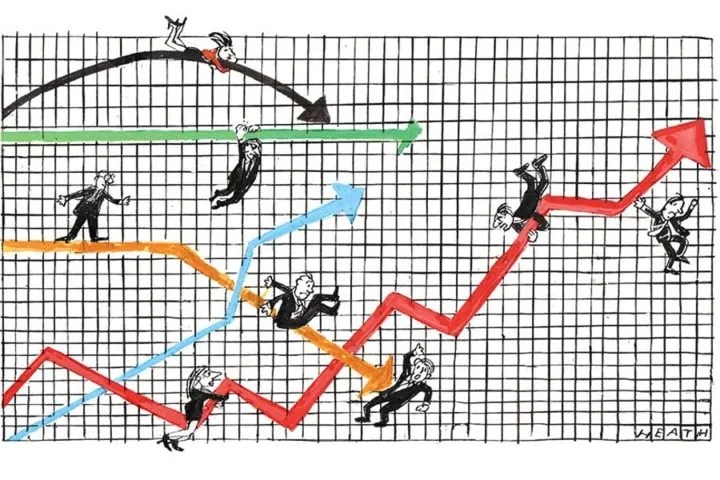

BlackRock’s UK chief investment strategist, Vivek Paul, has warned this week that pre-election promises of large tax cuts or spending increases could unsettle the bond markets again. There are clear echoes here of the turmoil that followed the Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng mini-Budget back in 2022. How worried should we be?

These warnings should not be dismissed lightly. BlackRock is a huge global player, with more assets under management than any other firm. Sentiment can be fickle and market selloffs are often self-reinforcing.

The mini-Budget backfired in part because of mistakes that no-one is now likely to repeat, such as sidelining OBR

There are also some reasons to think the market in UK government bonds, or ‘gilts’, might be particularly vulnerable to a buyers’ strike. For a start, the market for gilts is small compared to those for US treasuries or Japanese government bonds (JGBs), or the pool of bonds issued by governments in the euro area. It is not such a brave call for an international investor to go ‘underweight’ in the UK.

UK inflation has also been slower to fall, and the core rate (which excludes food and energy) remains relatively high. The Bank of England might therefore still be reluctant to lower official interest rates as quickly as other central banks. This could reduce the appeal of gilts, which have already rallied in anticipation of large rate cuts. In the meantime, the Bank of England is persisting with its policy of selling back the bonds that it had bought under ‘quantitative easing’, thus increasing the amount that must be purchased by private investors.

Finally, of course, many other commentors have pointed to the legacy of the Truss/Kwarteng mini-Budget. BlackRock’s Paul is not alone in suggesting that investor confidence in UK assets has yet to recover fully from that turmoil.

However, a sense of perspective is needed. Let us deal first with the points about Trussonomics.

History is usually written by the victors, and it may be hard to convince many people that the policies of Truss and Kwarteng were the right ones, just badly timed and badly communicated. Nonetheless, the mini-Budget backfired in part because of mistakes that no-one is now likely to repeat, such as sidelining the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). If anything, that experience has strengthened fiscal discipline.

The fallout was also exacerbated by heightened nervousness in global bond markets at a time when inflation was surging and other central banks were expected to continue raising rates aggressively. The global backdrop now is very different.

Finally, the turmoil in the UK markets might have blown over more quickly had it not been for the liability-driven investment (LDI) crisis, when some pension funds were caught out by the dramatic reassessment of the outlook for interest rates. That timebomb has now already gone off.

The scale of the new measures on tax and spending that are likely to be implemented by the Conservatives, or proposed by Labour, are also relatively small. Lower inflation and lower interest rates should give Jeremy Hunt up to £20 billion in additional firepower for the March Budget – plenty of room for a penny off income tax and some additional sweeteners on the spending side without worrying the markets.

As for Labour, the headlines have focused on the £28 billion green investment plan. But this is actually only £20 billion in additional spending, since it includes money already pledged by the Conservatives, and Rachel Reeves has stressed that it will be conditional on meeting the fiscal rules. Again, little to unsettle investors here.

Either way, even £20 billion is small beer in the context of overall public sector debt, which was £2,671 billion at the end of November.

The UK is not so much of an outlier either. The overall burden of debt can be measured in different ways, but relative to national income the UK is in a similar position to France and the US, and in much better shape than Italy or Japan. And of course, tricky elections are looming in other countries too – not least the US.

Above all, the key drivers of bond markets are expectations for inflation and interest rates. BlackRock may be cautious on the outlook for both in the UK. But also this week, Deutsche Bank, Investec and Oxford Economics have joined the growing band of commentators now predicting that UK inflation could hit the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target as soon as April. This would be more than a year earlier than the Bank had been predicting, providing the brightest of green lights for interest rate cuts.

In short, the fundamental case for holding gilts is still appealing and international investors should continue to give the UK the benefit of the doubt. There is no point in poking the bond market bears, but I suspect they will remain in hibernation for a long time yet.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in