The age of the car was a long time coming. The 19th century belonged to the train and, to a lesser extent, the bicycle. Several prototype automobiles were built during this period, but by the end of the century the technology was still primitive. In 1899 a handicap race held in France pitted walkers, riders, cyclists, motorcyclists and drivers against one another. The horses came first and second.

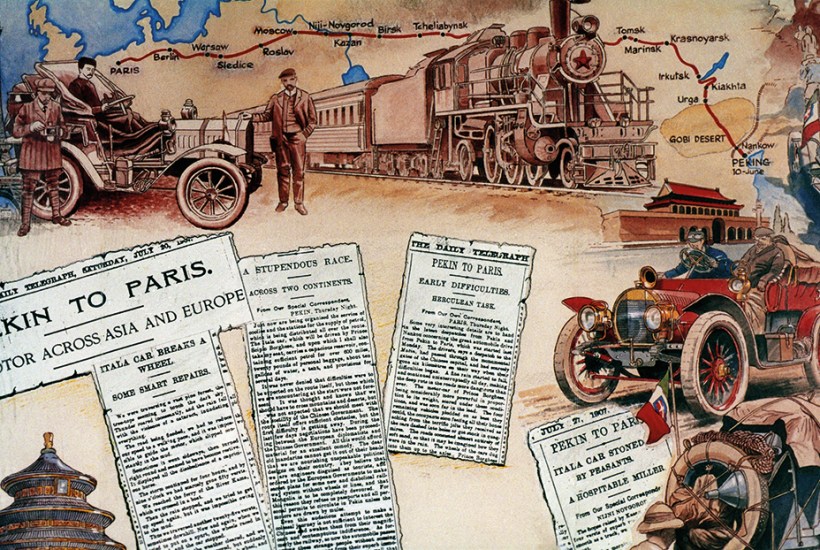

However, in the early years of the 20th century, a series of widely publicised challenges increased popular interest in motoring. The most ambitious was set in 1907 by the French newspaper Le Matin: a non-stop race from Peking to Paris, taking the car across mountains, desert and steppe to prove its practicality.

Just five vehicles entered the competition: a three-wheeled Contal Motori resembling a motorbike; a Dutch Spyker driven by a charismatic chancer named Charles Godard; a pair of cars from the manufacturers De Dion-Bouton, then the world’s most successful marque; and an Italian Itala five times the size of the Contal and six times the horse-power, driven by Prince Scipione Borghese, with a correspondent from the Corriere della Sera also on board and a family servant acting as mechanic and chauffeur.

This is the stirring story Kassia St Clair tells in The Race to the Future. Its opening pages resemble Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, the comic film from 1965 about a fictional air race to Paris. This contest features the same amateurish mix of competition, camaraderie, and national pride, as well as a larky sense of adventure: ‘Down goes the flag. Smash goes the bottle. Shards of emerald glass and champagne spume catch the light. The race from Peking to Paris has begun.’

To begin with, progress is slow. In fact travelling by car seems more a burden than a convenience (at one point four of the five vehicles manage just nine miles in nine hours). The competitors run out of fuel in the Gobi desert, lose their way crossing Russian forests filled with bandits, and get stuck driving over a river on a set of train tracks. That said, the worst delays are caused by poor roads – frequently mired in mud or flooded by rains – and the difficulty of acquiring petrol or spare parts. But the locals are often willing to lend a hand, transporting broken down vehicles by horse or barge. At one point a Russian carpenter even fashions a new wheel for the Italian team, communicating in the patchy Latin he learnt during one long winter.

Despite a gentlemanly understanding that nobody would be left behind, the teams soon separate. Before long the prince achieves an unassailable lead, removing most of the drama from the outcome of the race. He’s a glamorous figure, welcomed like a hero in half the cities he passes through, but too reserved to feel much enthusiasm for. His only rival in terms of narrative potential is the enigmatic Godard, who spends several weeks with his car out of action, before completing the intervening sections of the course in record time. But even with this Terry-Thomas approach to the rules, there’s never much chance of him catching the prince.

This story has been told several times before – including by most of the participants. However, St Clair’s account is blended with historical essays arguing that the race was an inflection point in history. As well as discussing the political situation in turn-of-the-century China and Russia, and the spread of technologies like electrical and wireless telegraphs, the author also looks forwards to the role of vehicles in the first world war, the dominance of cars in contemporary cities and the environmental damage caused by petrol-based engines.

In 1907, cars were still an eccentric hobby for millionaires and mechanics, but they would soon become a convenient means of transport for millions of people. As St Clair argues:

The idea that cars embodied elite status really came to an end in 1907. Already, on both sides of the Atlantic, increasingly affordable vehicles were being produced. Over the following century the automobile went from being an intrinsically luxurious object to an everyday one, a necessity.

Although, as the author admits, the real revolution came with the release of the Model T Ford the following year.

Whereas the race is a bit of a jolly, these sections give the book more depth. One of the most interesting explains the early popularity of electric cars – accounting for one third of all road vehicles in America in 1900. However, because their fuel could not be carried on board, and because they appeared less macho than the loud and smelly petrol-based alternatives, the technology was never pursued. Ironic that, a century on from the Peking-Paris race, the age of the electric car has finally arrived.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in