Miss Saigon may on the face of it seem like an odd choice of musical for Opera Australia to revive for a mass popular audience but the upshot is so sumptuous and stylish and moving that it would be nitpicking to object. Yes, you can say the show written by the creators of Les Mis Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boubill plays on oriental typology but so what? This is a slightly weird modernisation of that intensely poignant opera Madam Butterfly but there’s no need to turn wokeness into a kind of never-ending insomnia of rectitude. The heroine, the pure-of-heart prostitute who survives the fall of Saigon, is played magnificently by Abigail Adriano and she is matched by Nigel Huckle in a superb display of the art of the singer-actor and that’s true too of Laurence Mossman as the dark lord of totalitarianism who claims dominion over the poor woman.

This is the show with the helicopter, it’s a pyrotechnical tour de force and it’s also a terrific tear-jerker. There’s more than a little irony in the fact that Miss Saigon which allows the musical theatre to display Asian or Eurasian faces should be subject to criticism because of this.

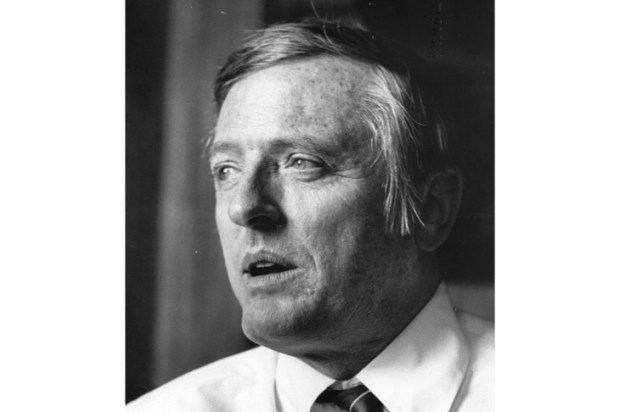

Nor is it fair to object to Opera Australia getting into bed with musical theatre in the way it does, something which we associate with that indefatigable showman of musical theatre the former head of Opera Australia Lyndon Terracini.

In practice, these things are a continuum. People start out with some school production of Gilbert & Sullivan or a recording of South Pacific that belonged to their parents and go on from there to Don Giovanni or The Marriage of Figaro. And this phenomenon is underlined by the fact that the original Emile De Beque in the Broadway production of South Pacific was Ezio Pinza, generally regarded as the greatest Don Giovanni of all time who was conducted in the role by Bruno Walter at the Met, the recording of which you can still get together with Ezio Pinza as Figaro in Le Nozze di Figaro. He was one of the greatest basses who ever lived and he makes operatic singing of the grandest kind sound easy because he gives it such idiomatic flow.

And it seems a bit of a category error to reduce every form of art and entertainment into the stereotypes into which they can be slotted. South Pacific is not an exercise in racism because of Bloody Mary and the French-singing kids anymore than it’s an attack on the little hick girl heroine Nellie Forbush. And it does include one savage and self-corruscating song against racism, ‘You’ve got to be carefully taught’. And The Mikado, the most over-the-top exercise in satirical orientalism in the history of operatic or sub-operating musical theatre has its starting point in the late Victorian cult of the Japanese. It’s a satirical homage to the fascination with the aesthetics of the Japanese and when you listen to the great patter songs like ‘I’ve got a little list’ – whether it’s sung by Martyn Green in clipped upper-class English or in the New York tones of Groucho Marx in his 1960 TV recording – there is not much doubt that the object of the satire is the audience.

It’s a complex question, how much a translation, at the highest literary level, should deliberately mime the foreignness of the original. Arthur Waley in his translation of that great sweepingly sophisticated novel of the heart and its complications The Tale of Genji begins, ‘There was an emperor, he lived it matters not when.’ And it’s staggering that a work of such self-conscious interior brooding, written by a woman, the Lady Murasaki – should have been written in the twelfth century. It’s no crime to attempt through a resonant stylisation to dislocate language into an echo chamber of its exotic strangeness.

Is the opposite true of the ‘new’ Beatles single ‘Now And Then’ which has shot to number one with its John Lennon vocal resurrected and clarified from an old scratchy recording on a tape? Is this the world of artificial intelligence coming to the rescue of a past we don’t quite have but which we can restore to life nonetheless? It also forms a pleasing pattern with the way Paul McCartney, ancient but unbowed, has been scintillating crowds in Australia.

Melbourne has been going through the Spring Carnival with the Melbourne Cup last Tuesday – the event which unites sport with fashion and style, high and popular, very much on display. The theatre has seen a musicalised version of Virginia Woolf’s gender-jumping extravaganza Orlando writ musical and also that toughest of contemporary dramatic intelligence, Patricia Cornelius, bringing to life the rough sexually abusive aspect male/female relations take on in the AFL. It’s called – with echoes of David Williamson – In The Club. Country clubs figure in one of the most delightful books Graham Greene ever wrote, Our Man in Havana, which is one of Greene’s entertainments and is all about the chap who’s commandeered by the secret service and sells them the supposed design for a nuclear weapon which is actually a vacuum cleaner. We had an odd experience with this because after being delighted once again with the book we decided to have a look at the 1959 film on YouTube. It’s directed by Carol Reed who made The Third Man from a Graham Greene novel and it has Alec Guinness as Wormold the mild-mannered hero and a star supporting cast including Noel Coward, Maureen O’Hara and Burl Ives. The only trouble is that Carol Reed has taken – tonally – all the comedy out of it. Guinness wanted to do it as comedy but Carol Reed stopped him and said, ‘Don’t act.’ He said Guinness wanted to get all the mildness of the character – he imagined him as the kind of person who would have a ball of string in his pocket – but Reed said to Guinness, who was one of the greatest character actors who ever lived, that he didn’t want any of his character acting. The upshot is to make Our Man in Havana which is a deeply funny and deeply humane book look like an absurdly plotted thriller which has gone off the rails.

Fortunately there’s Jeremy Northam’s superb narration on Audible which puts all the panache and whimsy, the delicious and absurd humour, back where it belongs.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in