Adam Sisman is sensitive to the charge that a book about an author’s unknown mistresses is simply an exercise in prurience. ‘I am not one of those who believes sex explains everything,’ he declares defensively.

But this admirably concise volume justifies its title. Sub-themes such as the practice and ethics of biography, and the emotional toll taken by spying, run through it. But its core relates how, when writing his 2015 life of David Cornwell (John le Carré’s real name.) Sisman was prevailed upon to delete details of his subject’s many extramarital affairs. In fraught pre-publication negotiations, he met Cornwell’s son Stephen, who suggested he keep this material as a ‘secret annexe’ to appear later.

This is that ‘annexe’ (everything seems to require the adjective ‘secret’). Sisman argues plausibly that Cornwell’s career in intelligence was uneventful, and well covered in his biography. Cornwell made it sound more mysterious than it was. Any idea that he was marked out to be head of SIS is rubbish.

But he used his experiences to carve a career as a hugely successful author of spy novels, and Sisman believes his self-confessed ‘messy’ love life is the key to unlocking his fiction. Cornwell himself told him that his infidelities ‘produced in my life a duality and tension that became almost a necessary drug for my writing’. Sisman concedes that they energised his world, acting as a substitute for espionage, and giving relief from the tedium of the writer’s solitary life.

Sisman traces the story back to Cornwell’s mother, not, as often mooted, his father. She deserted him at a young age and left him with a lifelong distrust of women. He compensated by marrying someone with a strong moral sense. He was faithful to Ann Sharp for eight years, but then the affairs proliferated. She objected to his writing and tried, he felt, to drag him away, in a manner similar to one of his lovers, Verity – the wife of his friend the writer Nicholas Mosley, Lord Ravensdale – who found her husband too preoccupied with his work, ‘his silent mistress’. Another early affair was with Susie, the wife of his close friend the novelist James Kennaway – a relationship which gave rise to the ménage depicted in The Naive and Sentimental Lover.

By then he had met Jane Eustace, who had previously been the literary agent George Greenfield’s secretary. Not only had she been Greenfield’s mistress, but, masochistically in Sisman’s view, she recommended him to Cornwell, who hired him as his agent. Having married David in June 1972, she became the gatekeeper to his world.

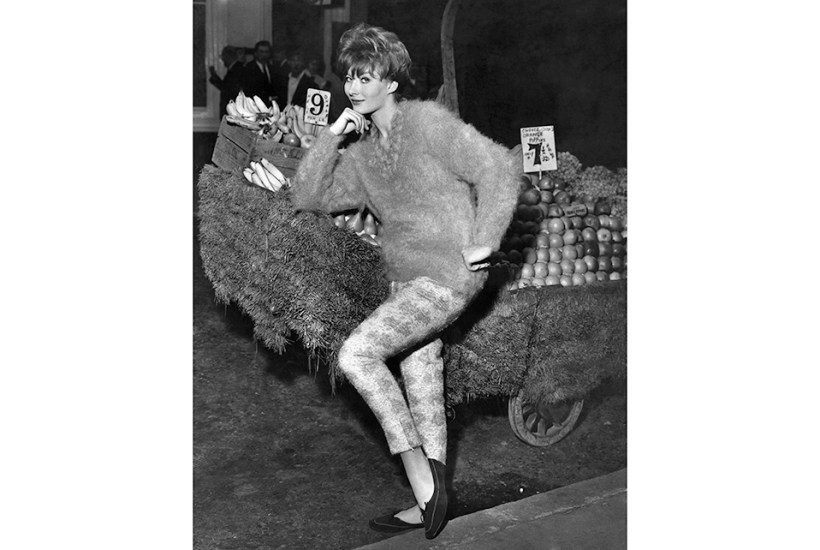

But he made clear he would continue his extramarital relationships, 11 of which Sisman has identified, though he is aware of more. Out of the 11, three have died and two didn’t cooperate, so Sisman focuses on the remaining six, of whom Liese Deniz seems the most intriguing. Born Norma Dennis in modest circumstances in Sheffield, she fled to London at the age of 16 and reinvented herself as a strikingly beautiful fashion model. Before long, in those socially mobile times, she was ‘publicly linked’ with Earl Mountbatten’s son, David, Marquess of Milford Haven. After her affair with Cornwell, conducted in a Primrose Hill flat apparently owned by his wife Jane, she married Lord Valentine Thynne, the youngest son of the Marquess of Bath, in 1977.

With typical largesse when romantically involved, Cornwell gave her a pearl necklace and a new Saab. She helped him research Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, and is credited with recommending Alec Guinness to play George Smiley. She was also the model for the character Lizzie Worthington, alias Liese Worth, who marries a Hong Kong tycoon-cum-Soviet agent in The Honourable Schoolboy. Previously unknown to Sisman, he came across her by accident when he met her daughter at a party.

Sisman himself kicked off this business of mistress-chasing with his own biography. There, for example, he fleshed out Yvette Pierpaoli, a sparky Frenchwoman in her thirties whom Cornwell met on a research trip to Cambodia. Her idealism was given fictional form in Tessa Quayle, who took on the forces of Big Pharma in The Constant Gardener.

Open season was declared on Cornwell’s private life last year when Susan (calling herself Suleika) Dawson, an abridger of audio books, published an account of her affair with the novelist, full of salacious details such as his delight in having ice cubes applied to his testicles. Editing his letters, Cornwell’s son Tim added new names, including the American museum curator Susan Anderson.

But gaps in the secret narrative remain. Sisman concentrates on Cornwell’s women, but says little about his business activities and wealth, for a long time overseen by Rainer Heumann, his Swiss literary agent and, in Sisman’s estimation, probably a spy. And Jane, now dead, remains a cipher. She occasionally protests, but one would like to know what she really thought.

Sisman candidly admits to ambivalence about his subject. Heartless philanderer or restless romantic? I imagine he’s sated with his exploits. But Cornwell’s output remains the most incisive chronicle of a murky era when the Cold War gave way to a late capitalist free-for-all where interests of state, finance and individuals collided. There are even rumours that George Smiley, like James Bond, is getting a posthumous reboot. A mistake, I’d say, but the le Carré estate is proactive and rich.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in