In 2012, Jeff Lynne released Mr Blue Sky: The Very Best of Electric Light Orchestra. Except it wasn’t. It was 11 new re-recordings of classic ELO songs – which isn’t the same thing at all. Lynne, bless him, believed that having gained more experience as a producer, he could now improve the songs that made him famous. ‘You know how to make it sound better than it did before,’ he said, ‘Because I have more knowledge… and technology.’ Sheesh. How wrong can one man be?

Pop music is all about the definitivearticle. Not only the bold prefix attached to its greatest practitioners – Beatles, Byrds, Wailers, Temptations, Fall, et al – but the notion of a defining recording of a song. The stage is the place for revision: to jam, change the words, the rhythm, the feel. The studio version, by contrast, is sacrosanct; these things are called ‘records’ for a reason, after all. They capture a moment by becoming a moment themselves, an aural photograph – sometimes sharp and clear, sometimes beguilingly out of focus. However much an artist might wish to recreate the original, or fix any perceived flaws, the results will always feel like Photoshop.

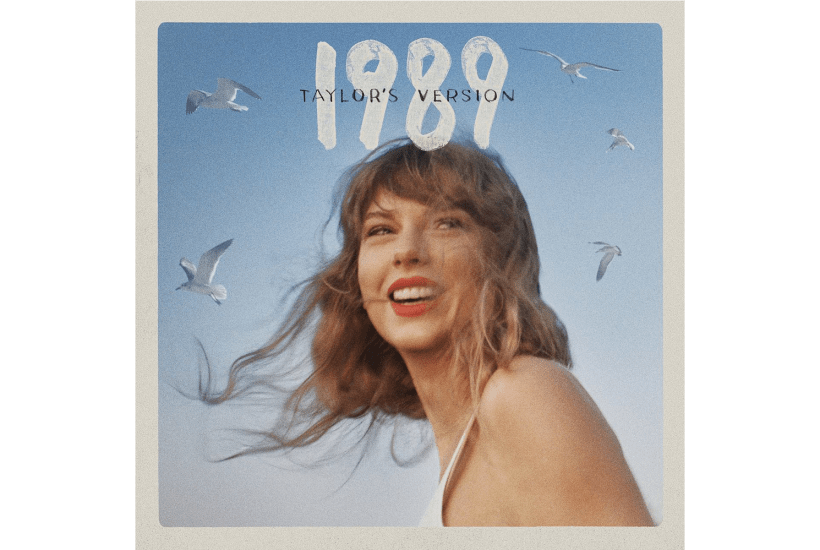

This week Taylor Swift continues the programme of recording new versions of her first six albums. She has got to 1989, for my money her best record, originally released in 2014. The planet’s biggest pop star has been up front about the reasons for this exhaustive and rather exhausting enterprise.

Swift signed to Big Machine Records in 2005, aged 15. By the time that contract expired in 2018, she had become a superstar yet Big Machine, not atypically, retained ownership of the master recordings of her albums. (Using her Big Time clout wisely, in her new contract with Republic Records, Swift secured ownership of all future masters.) Big Machine was sold to Ithaca Holdings, a private-equity group owned by music mogul Scooter Braun. Swift has no love for Braun, who manages her nemesis, Kanye West. The feeling is reciprocal. When Braun sold her recordings to another company, Shamrock Holdings, for $300 million in 2019, a reported stipulation of the sale was that Shamrock could not sell them back to Swift.

Swift wants ownership of her work, which seems reasonable, but is unable to get it. Instead, she is recording her first six albums again – sweetened with copious unreleased tracks – and encouraging fans, radio stations, streaming platforms and film and TV companies to default to the new versions rather than the old.

This, in effect, is the law of the corporate music jungle playing out as a personal beef. Fans cheer on Swift for taking a principled stand – which requires them to buy the same material for a second time – while (mostly) preferring the originals they fell in love with.

The implied premise of Swift’s re-recording programme – that the original versions are somehow tainted, and the new ones more authentic – contravenes the unspoken agreement an artist makes with their audience. The song is not the record, and the record is not the song. The record is a mythical ‘other’. Within those three-minute symphonies, ‘every scratch, every click, every heartbeat’, as Elvis Costello put it in ‘45’, is imbued with meaning. Poke around with the time-space continuum at your peril.

This is not a new thing. Frank Sinatra and Chuck Berry re-recorded their old material for contractual reasons. If you bought best-of albums by the Cure and Kate Bush in the mid-1980s, you would find versions of their earliest hits – ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ and ‘Wuthering Heights’ respectively – with a new vocal replacing the old one.

This kind of revisionism has simply become increasingly common since the bottom fell out of the record market, and licensing became more significant to an artist’s income stream. A couple of years after Lynne, Blondie re-recorded their biggest hits on Blondie (4)0 Ever. Having laboured under a terrible record deal in their earlier days, this was an attempt to get new versions out there that might make them some money.

Debbie Harry might reason that the average Spotify user doesn’t much care which version of ‘Sunday Girl’ they are hearing, and she might well be right. Pop is undergoing a process of classical music-fication. Analogous to the demise of the physical single, there has been a shift away from the idea of a definitive reading of a piece of music. If you can’t hold the damn thing, it could be anything. Technology has made it easier to cut and paste, to elide past into present with barely a glitch. AI will finish the deal. Plausible versions of classic songs can now be created by a bot. In time, fewer people than you might think will care, or even notice.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in