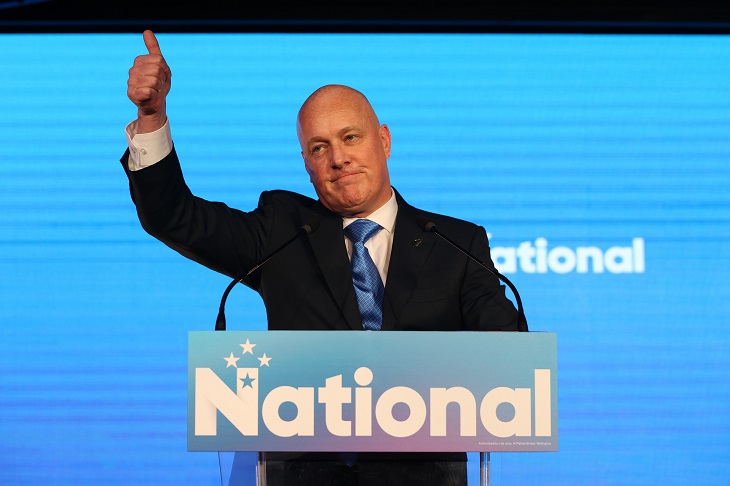

New Zealand’s October 14 election coincided with the Voice referendum where Australians decisively said ‘No’ to enshrining divisive race-based politics in the Constitution. Watching from across the pond, New Zealanders might reflect on the Australian experience that divided and continues to divide the nation as elite activists double down on their pre-referendum positions.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Get 10 issues

for $20

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $20.

- Delivery of the weekly magazine

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in