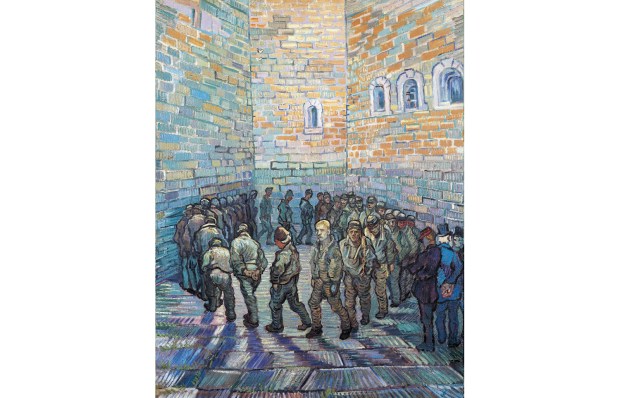

A heavily made-up Iranian woman in bra and knickers is dancing seductively before me. We’re in some vast warehouse, and she’s swaying barefoot. But then I look around. All the other men here are in military uniforms and leaning against walls or sitting at desks, smoking and looking at her impassively. I slowly realise we are in a torture chamber and this lithe, writhing woman is dancing, quite possibly, for her life. Me? I have become one of her tormentors.

Welcome to The Fury, a bravura attempt by Iranian artist Shirin Neshat to use virtual technology in her art.

‘Have you ever experienced VR before?’ asks the assistant as she adjusts my goggles, while I sit myself on a stool that rotates through 360º. Only once: I was across town at the Saatchi Gallery, masked up and sitting on a chair that came to life, hurling me forward to explore a simulation of Tutankhamen’s tomb. It gave me, perhaps, an experience akin to what Howard Carter felt in 1923, entering chambers that had lain in darkness for millennia.

Neshat’s film similarly puts me in someone else’s shoes. First of all I seem to be viewing the dance through the eyes of a military thug. Neshat tells me she modelled the men in her film on Iran’s Revolutionary Guard and indeed the actors she’s employed superbly incarnate the kind of moral void that might allow them to commit unspeakable atrocities.

But then the point of view shifts and I become the nameless dancer, sidling up to a particularly hard-faced brute leaning against the wall. As I approach, he blows smoke into my face.

Then the point of view shifts once more. I’m no longer a patriarchal goon or vulnerable dancer, but a voyeur watching the woman reel backwards from the smoke. Her body, I notice, is now covered in bruises and scratch marks. Perhaps those cigarettes have been stubbed out on her body. Clearly wounded, she stumbles, falls, gets up, tries to dance.

I swivel on my stool as the guards form a circle and walk towards me. I am, most likely, next to become a human ashtray. I’m not sure if, as the bumf suggests, this gives me, a pampered Englishman, a sense of what ‘it’s like to be an objectified woman in Iran’, but it certainly made me panic.

In a month in which we saw footage of Iran’s morality police beating a teenage girl into a coma on a metro platform for not wearing a headscarf, and in which the imprisoned human rights activist Narges Mohammadi won the Nobel Peace Prize for campaigning against repression in Iran, The Fury might seem only topical within the homeland from which the artist is exiled. Neshat, who lives and works in Brooklyn, argues The Fury may primarily confront women’s repression in her homeland, but hardly stops there. ‘All she has is her sexualised body, all she has is to make herself into a thing for her oppressors.’ says Neshat. ‘That is not just something that happens in Iran.’

The Fury is just one of a curated spate of VR artworks screening as part of the London Film Festival’s Expanded strand in the Bargehouse at Oxo Tower Wharf. You can immerse yourself in the experience of being in war-ruined Ukraine, go on the run from the Holocaust, or even become a mushroom.

Is it appropriate to exploit real life horror for sensory titillation? And can VR really escape its tragic-comic aura of being the means by which Mark Zuckerberg tanked his noxious social-media company? Certainly Meta’s current TV ads insist that VR technology is a boon: it will help medical students learn how to do eye operations in cyberspace before performing them in reality. But sometimes VR looks like the dead end on the way to transhumanism at worst, and at best just another piece of kit destined for technology’s discard pile along with Wii wobble boards, vintage Game Boys, Atari Pong consoles and eight-track tape players.

Ulrich Schrauth, who is in charge of the Expanded programme, insists there is more to VR than that. That it take us where other technologies fear to tread.

VR ‘immersion’ is everywhere in London this autumn. Across the river, the 400th anniversary of the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio will next month be the pretext for what’s being called an ‘immerzeo’, a means of immersing pilgrims as they wander through the City of London in the time and place of Shakespeare. As you stroll down, say, Cheapside, you will be able to hold up your phone or tablet and see projected images of what the city would have been like in the early 17th century.

Meanwhile, in Mayfair, Manolo Blahnik will soon open his multi-sensory VR experience at xydrobe, a new ‘luxury virtual reality destination’. Here, you will be able to sit at a virtual replica of the designer’s desk and be whisked via visuals, smells, wind and surround sound into the world of the shoemaker’s art. It could be more blah than Blahnik, but let’s see.

The most powerful of the VR experiences I see as part of the London Film Festival is Darren Emerson’s film Letters from Drancy. It documents Holocaust survivor Marion Deichmann’s time on the run from the Nazis when she was a child. With headset on, I am transported to the back of a truck in which little Marion and her mum flee occupied Luxembourg for Paris.

Letters from Drancy is by no means the most sophisticated VR film Emerson has made. In Pursuit of Repetitive Beats required visitors to wear not just VR headsets but backpacks pumping out thumping bass sounds the better to recreate Coventry’s acid house rave scene.

That said, one of the things that makes Letters from Drancy so potent is its combination of VR and other media. Once installed in a Parisian apartment, Marion and her mum get a fateful knock at the door. It’s the French militia who have orders to arrest mother but not daughter. This scene is reconstructed as a black and white 3D stop-motion animation, with Emerson’s nine-year-old daughter serving as the model for the little Marion.

‘I remember the last thing she said to me was, “Be good, I’ll be back”,’ Marion Deichmann, now aged 91, tells me. But she never saw her mother again.

After Alice Deichmann was transported to the holding camp at Drancy, little Marion and her grandmother fled Paris. Thanks to the Resistance, she was able to live for the rest of the war in a safe house with a sympathetic French family in Normandy. During her time there, Marion received postcards from her mother telling her not to worry and that she was going to join an aunt. Both were murdered as soon as they arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on 27 July 1942.

At one point in the film, we see Marion Deichmann on a recent visit to Drancy, now a Parisian suburb. In the middle of a square is a Holocaust memorial, including a cattle truck of the kind that transported her mother to her death. ‘I had never been to Drancy before we made this film. It was then that I broke down.’

I watch several visitors in tears after watching the film. The radical empathy that Schrauth thinks VR storytelling offers seems at its most valuable here. Deichmann quotes to me from Primo Levi’s poem from the start of his Auschwitz memoir If This is A Man imposing on us the duty to remember. Perhaps VR might help with that obligation.

It might help to do other things too. Not least demonstrate to us that we risk falling into a future worse than Orwell imagined. I stumble into another room where Karen Palmer has created a VR experience called Consensus Gentium about facial recognition software and all the other paraphernalia of the surveillance industry that gives me the willies. There are no goggles but you stare gormlessly into a smartphone and become immersed in a scintillating VR experience that unfolds like an episode of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror. The phone uses artificial intelligence and facial recognition technologies to analyse my gaze and emotions in real-time, and thereby to shape narrative. The data culled from my eyes also decides whether I am entitled to download an app that accords me credits and decides on my social status, my employment chances and whether I should be treated as a law-abiding drone or enemy of the state.

Consensus Gentium isn’t just an immersive satire on AI and social media but also a morality tale about how facial recognition is often racist: studies have suggested that the darker your skin tone, the more likely you are to be misidentified by facial recognition software.

At the end of the experience, I am pleased to learn that I have been deemed an enemy of the state and locked out of all its apps. True, I am now functionally unemployable and social kryptonite but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in