The unlovely Rose Theatre in Kingston is a modest three-storey eyesore. The concrete foyer looks like an exercise area on a North Sea oil platform, and the auditorium itself is a whitewashed rotunda that resembles the chapel in a newly built prison. Yet this cheerless, functional space is perfect for a mischievous new satire, Shooting Hedda Gabler, about recent developments in the acting trade.

The central character, Hedda (Antonia Thomas), is a washed-up American starlet who wants to gain artistic credibility by taking the lead in a pretentious film version of Hedda directed by Henrik, a tyrannical Norwegian auteur. ‘There is no script,’ he announces on the opening day. But he’s lying. The script exists in his head and he barks out lines and stage directions which his cast must enact as he commands. And he films every moment of rehearsals so the actors get no chance to relax or to improvise on their own terms. Henrik sounds like an irritating swine but Christian Rubeck plays him as an interesting but unpredictable nutcase who might be fun to work with.

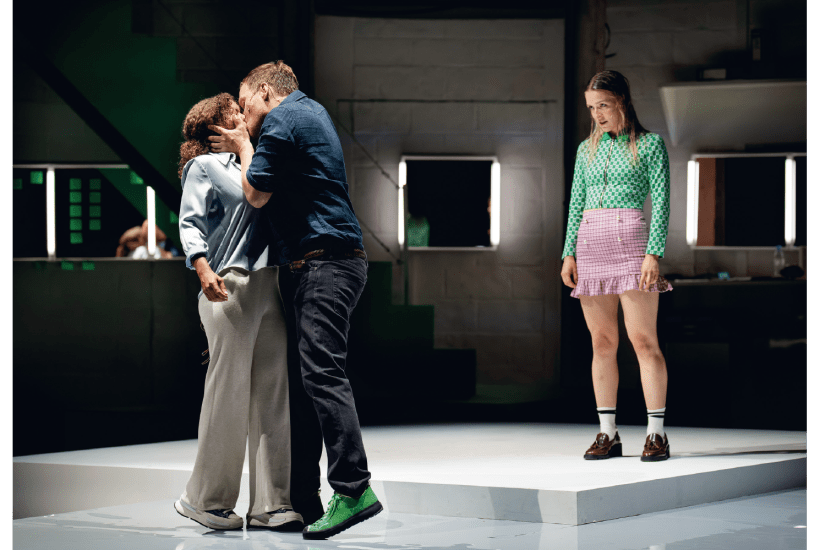

Thanks to the #MeToo movement, the set features an ‘intimacy co-ordinator’ who oversees all physical contact between cast members and makes certain that no inappropriate touching takes place. But Henrik constantly gropes and assaults Hedda with complete impunity because his intimacy co-ordinator is on the pay roll, and she feels obliged to do his bidding. The same applies to the on-set therapist (amusingly played by the same actress) who uses her scientific authority to give Henrik a free hand and to let him do whatever he likes. The safety inspector, who happens to be Henrik’s assistant director, also rubber stamps his decisions and fills in the paperwork to suit his wishes. This illustrates a truth that many of us had half-suspected: the type of person who works as an ‘intimacy co-ordinator’ is a spineless busybody whose loyalties can easily be coerced. On Henrik’s film set, the new roles are seamlessly incorporated into the time-honoured hierarchies of power. It’s as if the #MeToo movement had never happened. The gropers grope, the victims endure, and the witnesses say nothing because they don’t feel entitled to speak out. It’s no coincidence that Henrik is a handsome alpha male and the minions he mistreats are all fey, soft-hearted women. That’s part of the gruesome joke.

The second half turns into a different creature as the film becomes a parody of the original story. Ibsen’s play culminates in a fatal shooting and a destructive fire, and the same elements occur here but with new results. Hedda’s loaded gun is on stage throughout Act Two and this creates a delicious atmosphere of tension and uncertainty. Someone is bound to die. But who? And when? Will Henrik get a bullet in the skull? Might the useless ‘intimacy co-ordinator’ be gunned down? Or will the much-abused Hedda turn the weapon on herself? The closing scenes are as gripping as an Agatha Christie thriller. This ingenious and amusing skit is a must for anyone who works in the theatre.

Richard Jones has created a low-budget version of Pygmalion at the Old Vic. The play opens in Covent Garden beneath the famous pillars of St Paul’s church which look like rolls of fibreglass painted beige. Some scenes are set in a vintage recording studio, for obscure reasons, and the constant use of harsh spotlights makes the show difficult to watch. Too often, the actors’ faces are in shadow. Racy music and bustling passages between the scenes feel like an attempt to transform Shaw’s comedy into an animated crime cartoon, like an episode of Tintin. But what for? The costumes and the hairstyles are a mishmash of influences that date, rather vaguely, from around 1925 until about 1960. The men’s suits belong to the 1950s. The women’s head-dresses owe much to the 1920s but their frocks seem to have been designed in the post-war era. As is often the case, no clear advantage is won by updating the script. But the result is to soften the impact of phrases like ‘what the devil’ and ‘not bloody likely’ which sound harmless now but were scandalously obscene before the first world war.

Patsy Ferran screeches her head off as Eliza in the early scenes. It’s grating to sit through but these eruptions of howling are what the script demands. Her transformation into a sophisticated Mayfair beauty is magnificently done. Bertie Carvel’s Higgins emphasises all his least likeable qualities. He’s vain, aggressive and pitilessly inhumane. And he’s so fixated with the minutiae of phonetics that he can’t form proper relationships with women, although he gets on fine with his boorish, hectoring mother. This is a highly successful portrait of a geek who suffers from ‘high-functioning autism’, as we call it now. The Higgins that Shaw wrote was a loveable English eccentric. Something’s gone missing here. The warmth.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in