A recent Sunday Feature on Radio 3 contained some of the best insults I have ever heard. Contributors to the programme on the early music revolution were discussing the backlash they experienced in the 1970s while reviving period-style instruments and techniques. Soprano Dame Emma Kirkby remembered one critic complaining that listening to her performance was ‘as about as interesting as eating an entire meal of plain yoghurt’. Another critic, writing in Gramophone, pronounced the strings of the new ensembles ‘as beautiful as period dentistry’.

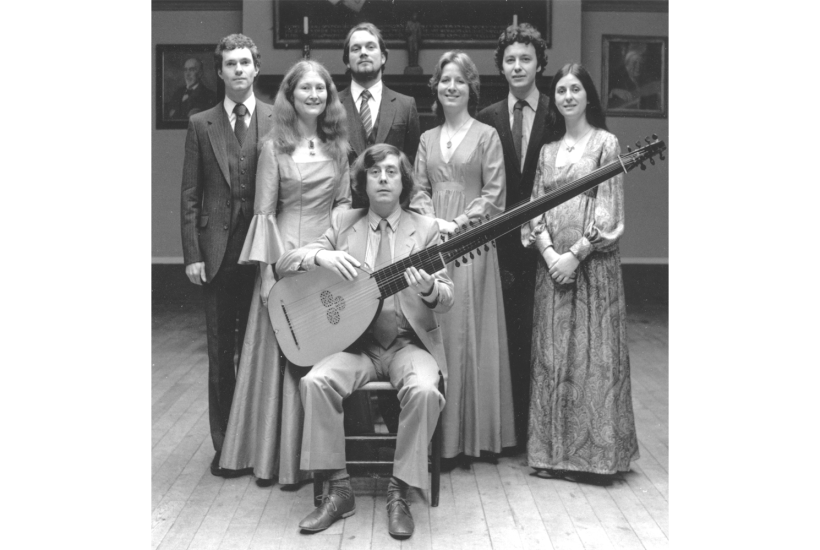

Those strings were mostly made of animal guts. There was, as one of the musicians interviewed recalled, ‘a DIY atmosphere’ to the movement, which developed alongside a spate of others in 1973. A fresh interest in medieval and renaissance music and historical treatises had spawned an appetite for ‘authenticity’. Singers turned to the Tudor-centric Clerkes of Oxenford for inspiration. Other musicians were awakened to the folly of making 18th-century music sound like 19th-century music by using metal strings. Their solution was to do away with modern instruments and excessive vibrato and plumb the depths of a more prosaic playbook.

To many professionals, this represented little more than ‘pointless archaeology’, for the results were seldom sparkling. Listening back, one of the members of the newly formed Academy of Ancient Music confessed that their sound was ‘a bit ropey’ but had ‘a certain dash and pizzazz’. To a conservatoire-trained ear it was little more than ‘mouse music’. Imagine the critics’ annoyance when the mouse-musicians scored a Decca LP.

Listening to the interview-rich programme, presented by a jolly yet unobtrusive Sir Nicholas Kenyon, it was clear that we were meant to come away thinking this movement hugely revolutionary. But was it not inevitable that gut-strings would enjoy a renaissance, as fashions changed?

Still, the programme was hugely entertaining. The bitchiness of the critics and holier-than-thou nature of the retorts of the historicising musicians had me smiling throughout. It was all very well for sceptics to frown upon the newcomers as besandalled brown-rice eaters, but the newcomers could simply look down at their gut-strings and say: ‘If they were good enough for Bach, they are good enough for us.’

Bach is apparently a favourite among the bee community. In Five Cellos: Lost and Found, also on Radio 3, musician Kate Kennedy played some Bach on a cello in which some 400,000 bees have taken up residence. We had to take her word for it, but as she began Bach’s First Cello Suite, the bees froze like a rapt concert audience. They have been inhabiting the instrument on a Nottinghamshire estate ever since an apiarist-physicist, Martin Bencsik, invited them in. Their own playing isn’t up to much – as the wind blew through the instrument it sounded like microphone interference – but they seemed to enjoy being played to. Some nice relaxation after a long working day.

This was one of the lighter episodes in the series of five which aired in The Essay slot last week. The theme of ‘lost cellos’ led us to some truly haunting locations. In episode one, Kennedy travelled to a Lithuanian ‘fort of death’ where Jewish-Hungarian musician Pal Hermann was killed during the second world war. The story of his lost Gagliano cello was extraordinary. I won’t spoil it here, only note that it is still missing and bears an unusual inscription, ego anima musica sum (‘I am the soul of music’), on its side. In another episode, Kennedy interviewed Auschwitz-survivor and cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, now 98, who as a child was recruited to the camp orchestra.

At the beginning of the series, and at passing moments throughout, Kennedy reflected on her own life with the cello and the sense of loss she feels at being limited in the ways she can now play it due to injury. The concept of an instrument as an appendage is so familiar that it felt clichéd until each story was told in full.

Kennedy interviewed both Pal Hermann’s daughter and Lasker-Wallfisch, whose voice, we were told, is a ‘low Marlene Dietrich mezzo’. The decision to report their words rather than play the recordings was understandable. It would be inadequate to call their stories moving. If you come to the series doubting the importance of music and the inseparability, as Kennedy described it, of musician and instrument, these accounts will irreparably change your mind.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in