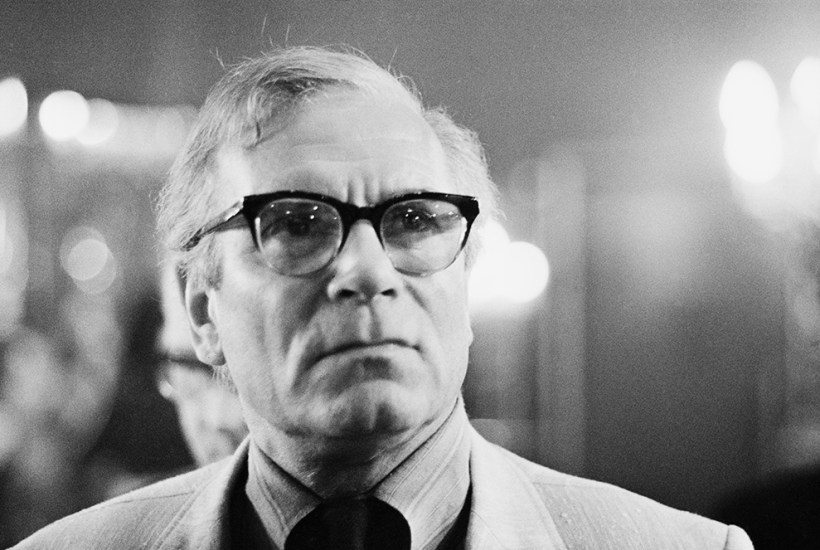

The Australian Book Review poetry prize is upon us again and it’s worth mentioning that the ABR editor Peter Rose, a poet himself, has named the prize the Peter Porter Poetry Award. Peter Porter, a quiet and characteristically modest man, would never have claimed to have the gift of that most abundantly talented poet Les Murray who dedicated his poems ad majorem dei gloriam (to the greater glory of God) as if he were reaching out for a dedicatee equal to his own splendour. Enough lovers of poetry will tell you that Peter Porter had greater depth and poignancy. Every Australian kid at high school should know this poem which is one of the greatest poems written by any poet, Australian and otherwise, since the second world war – ‘Non piangere, Liu’ (Do not cry, Li Hu) – the title is from Puccini’s Turandot and is one of the staggering poems Peter Porter wrote after the suicide of his first wife. …You need answer none of them. / Nor my asking you for one drop / of succour in my own hell. / Do not cry, I tell myself, / The whole thing is a comedy / and comedies end happily. / The fire will come out of the sun / and I shall look in the heart of it.

Grief and the depth of loss gave Peter Porter a supreme desolating subject and in the poems collected in The Cost of Seriousness he was equal to it. It is a fine and fitting thing that his name be kept before the public with the ABR poetry award just as it is shrewd and worldly in a wholly admirable way that Peter Rose should combine an entrance fee with various subscription offers. The prize can be won by all comers national and international and is worth $10,000. And it should be said that with its comprehensive daily arts coverage ABR is a testament to Peter Rose’s passion for the arts.

Peter Porter was one of those expatriate Australians who carried his ancient nationality with an easy grace. He used to tell stories, against himself, about how as a teenager his father would toss down beer from the bottle with an indigenous man on a boat whereas he was too squeamish himself. He seems to have educated himself with absolute thoroughness in Brisbane (belonging to reading groups that lapped up Arden of Faversham and all those arcane neo-Shakespearean plays) in a way that is shared by that other Queensland polymath, David Malouf. Porter didn’t even go to university (and he abhorred Cambridge because unlike Oxford, with its car industry, they did nothing but talk and teach). He was genuinely amazed when Frank Kermode, the eminent critic, took the chair of the British Academy when Porter was elected to it whereas for all his knighthood and sometime Cambridge chair Kermode would have thought he was unworthy to untie Porter’s sandal.

He was also amazed when the great New York critic Susan Sontag wrote to Scripsi about him. ‘I’m amazed she’s ever heard of me,’ he said in wonder. But he was proud to have been told by William Empson, the doyen of literary critics, whom he interviewed, ‘Poets don’t stink.’ And he was also proud to have seen the world premiere of Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd and of Olivier doing John Osborne’s The Entertainer. His favourite Hamlet was Albert Finney and he thought the 1951 recording by Knappertsbusch of the overture to Wagner’s Parsifal was the zenith of sonority. He would never deny that Mozart and Bach and Beethoven were the supreme composers but the dazzle and range of Schubert made him gape. He was an early mentor of Martin Amis and loved those Charlotte Street lunches. You could stand with him outside the Odeon in Piccadilly Circus as tens of thousands of Madonna fans thronged and he would say, myopically, ‘Nothing going on here,’ restive for the next pub.

Last week’s talk of the national theatre never touched on Michael Blakemore, the Australian who was an associate director of Britain’s National Theatre in Olivier’s day and directed him in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night and did the legendary premiere production of Michael Frayn’s Noises Off. He’s still with us at the age of 95 even though his memoir Arguments with England details how he was an understudy in the legendary 1959 season at Stratford with Paul Robeson as Othello, Olivier as Coriolanus and Charles Laughton as Lear. Blakemore says Laughton couldn’t really conjure Lear’s whirlwind of rhetoric but that he did the scene with Gloster (‘We cry that we are come to this great stage of fools’) in a way ‘that almost transcended acting’. One of the lieutenants of the progressivist group at the Sydney Theatre Company, Tom Wright, said he was amazed by the attention Blakemore as a director gave to the voice. You can see him play John Curtin in The Last Bastion on Prime. More than sixty years ago he was the lover of Vanessa Redgrave and was appalled to discover the other man in her life was his enemy Peter Hall, the man who had said any director would benefit from a Cambridge education. Never mind that his friend John Barton had never commanded a professional stage.

One award that has come out recently is the Ned Kelly Award for crime writing which went to Jane Harper for Exiles. She became very understandably famous for The Dry but this one is bamboozling because of the proliferating cast of characters. And isn’t there something weird about a prize for a work of popular (i.e. trash) writing?

Well, maybe not. It’s weird for a critic to discover years after her debut that Favel Parrett is a master of narrative. She has her second children’s book, Kimmi, coming out from Hachette in November as a paperback for $19.99 and she can spin a sentence that will have lovers of the music of prose lining up. And who can doubt the audience for Peter FitzSimons’s book The Last Charge of the Australian Light Horse. His book deal for Brittany Higgins almost overshadowed his sheer popular ease but the very blurb for the book, the evocation of Gallipoli, the brothels and the brotherhood, the sheer dash and vigour, is enough to make the most sceptical mouth water.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in