In recent years when we’ve talked about the relations between India and the West, we’ve gone back to stressing the impossibility of interchange. A hundred years ago, E.M. Forster ended A Passage to India with the certainty that Aziz and Fielding could not be friends. Forster thought things would be different after Indian independence, but the spectres of cultural appropriation and the assertion of ongoing imperialist guilt have discouraged equal exchange.

That may explain why the excellent story Mick Brown tells in The Nirvana Express has hardly been covered in the past. How western travellers to India went from sober, interested inquiry to a weirdly content-free fantasy existence, and how some sharp-minded Indians saw an opportunity to make a lot of money and garner a good deal of vulgar status are questions that don’t always show the participants in the best light, and writers have stayed clear.

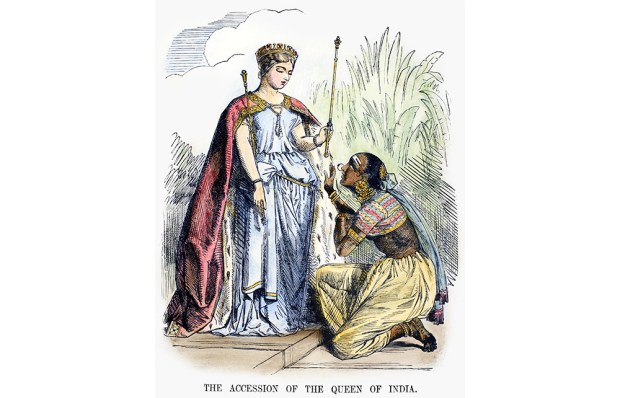

In the first stages, western (principally British) observers of Indian culture were driven by scholarship and sustained by responsible investigation. Although it would not be true to say that the British were primarily responsible for an understanding of Indian culture (some maharajahs maintained scholars in their households in the same way as they provided for artists and poets), they certainly took things a step further. Sir William Jones’s researches into Sanskrit resulted in an unprecedented understanding of relationships between the Indo-European languages. Francis Buchanan, an East India Company official, surveying Bihar in 1811, rediscovered the long forgotten site of the Emperor Ashoka’s shrine at Bodh Gaya, the site of the Buddha’s first enlightenment. These men were discoverers of truth in another culture, though of course a place must also be found for orientalists such as Charles Wilkins, who in 1785 produced a translation of The Bhagavad Gita and introduced the West to a then unfamiliar culture.

Serious investigation by western scholars continued, but Brown’s interest moves entertainingly to those whose idea of India was less rigorous. Through Edwin Arnold’s long poem The Light of Asia (1879), the Victorian general reader became acquainted with the Buddha’s teachings. This poem was less a sumptuously oriental Fitzgerald-type Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam than an attempt at a kind of Essay on Man about an eastern religion:

Life runs its rounds of living, climbing up

From mote, and gnat, and worm, reptile, and fish,

Bird and shagged beast, man, demon, deva, God,

To clod and mote again, so are we kind

To all that is…

The Light of Asia was immensely popular (in 1902 the first westerner, an Irish migrant worker, was ordained a Buddhist monk), and from it sprang the richly amusing line of charlatans, mountebanks, gulls, knaves and opportunists that provide the meat of Brown’s book.

Indians had been coming to the West for generations – Dickens met Rabindranath Tagore’s moneymaking grandfather Dwarkanath – but now a wave of mystics arrived. Among the first was Swami Vivekananda, an honourable and sincere man whose appearance at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893 unleashed mass hysteria. Annie Besant, the theosophist, was swept away; Mrs Roxie Blodgett, an Indiana businessman’s wife, was thrilled to see ‘scores of women’ besieging him. He was signed up immediately by an American speakers’ agency. Other theosophists spread the word, including the glamorous Madame Blavatsky, aiming to link all the world’s religions.

It is easy to be amused by the overheated and slightly vacuous content of the theosophists and other enthusiasts for Vivekananda. But this was a period of intense intellectual ferment when all sorts of new movements were being touted. Some, like women’s rights and vegetarianism, flourished; others, such as theosophy, spiritualism and nudism, quickly found their natural limits. More gurus started to be promoted. It is around this time that E.F. Benson produced the deathless episode in Queen Lucia when a swami teaching yoga arrives in an English village – who of course turns out to be a cook at a London Indian restaurant, ordering brandy on Daisy Quantock’s account. Some of these characters were intelligent people, talking to other intelligent people; some were brazen chancers, seeing, with Vivekananda’s triumph in mind, an opportunity to exploit rich, naive westerners.

In 1930, a failed London bookseller and publisher, an associate of the Satanist Aleister Crowley, set off for India in search of spiritual enlightenment. Paul Brunton came across a mystic, Meher Baba, via a recommendation from a fellow Crowleyite. Meher had taken a vow of silence five years earlier and communicated by means of an alphabet board. He informed Brunton that he was preparing to convey a spiritual message to the world. In 1931, aged 37, he announced: ‘Love calls me to the West. Make preparation.’

In London and then more profitably in America, Meher impressed his hosts with his spirituality, often reducing them to tears. He knew everything. Not that he read the newspapers – ‘he places his hands and fingers on the printed words’ – or even books. It was really only when he hit Hollywood that doubts began to surface. Much of his spiritual energy started to be devoted to engineering a meeting with Greta Garbo and persuading the studios to make a massive movie about his life.

In these circumstances, decent, honourable Indian thinkers grew baffled by the lack of engagements. Another of Brunton’s finds, Sri Ramana Maharshi, emerges as a thoughtful person, slightly perplexed by the questions of his strange visitors and giving them the politest brush-offs. By now Meher had taken to adopting madmen for a week or two until they bored him, including a man who ate coins, waited until they emerged in his faeces and then ate them again. Brunton asked whether Meher was, as he claimed, the avatar of a god. ‘Everyone is the avatar of a god,’ he was told. The situation is gloriously dramatised in Half a Life, a late novel by V.S. Naipaul, in which the search for meaning by rich westerners creates a moneymaking guru.

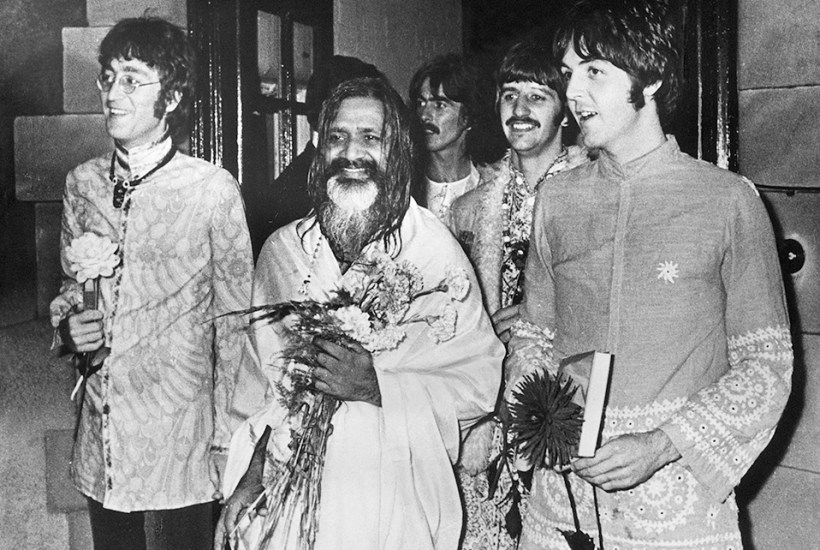

At a certain point, the enthusiastic quest for not very meaningful pieties got overtaken, and was combined with a wider enthusiasm for drugs. Quite what the taking of industrial quantities of LSD had to do with the proponents of eastern philosophy ought to have been asked more often than it was. The Beatles’s famous Maharishi Mahesh Yogi put up with a lot for the sake of his famous followers and lost no time in advertising them in order to drum up more business. The song ‘Sexy Sadie’ on the White Album goes: ‘What have you done?’ But it should have been ‘Maharishi, what have you done?’ The lyric had to be changed for fear of the Maharishi’s lawyers descending with a defamation suit.

Some of these versions of Indian culture and thought were remote indeed from the original. Jack Kerouac planned to start a Buddhist monastery in Mexico dedicated to ‘pure essence Buddhism… that would be, I ’spose, no rules’. Brown wryly comments that this ‘would have made it unique among Buddhist monasteries throughout the world, which generally have more rules than the British civil service’. When such followers went to India, they generally saw only what they expected to see. ‘Everybody in India is religious, everybody on to some sadhana,’ Allen Ginsberg wrote, which might have surprised the argumentative lawyers and dandy litterateurs of Calcutta. Sometimes this led to real conflict. One mystic, Rajneesh, declared himself the ‘rich man’s guru’ and encouraged sexual libertinism. The locals living near his ashram found the sight of westerners dressed as monks or nuns copulating in the street difficult to deal with.

Increasingly, the problem was solved by creating a sort of Indian spiritualism which was basically run by westerners in their own projection. Hare Krishna was invented by a pharmacist on New York’s Lower East Side in 1966. In a sharp novel, John Updike has a charismatic guru turn out to be one Art Steinmetz from Massachusetts. This is far from implausible. A Buddhist philosopher, Anagarika Govinda, was a German called Ernst Hoffmann. Krishna Prem turned out to be a Ronald Nixon from Cheltenham. Madhava Ashish was in reality a former RAF engineer, Alexander Phipps, with a disconcertingly unmystical style of banter. ‘Aren’t you the chap who got bounced from Harvard?’ he asked one seeker after knowledge.

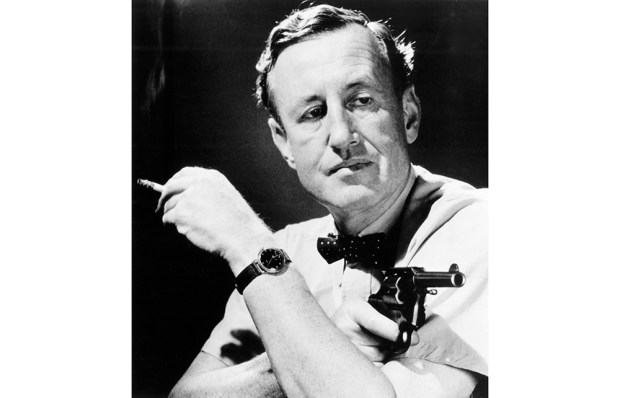

The Nirvana Express is a drily amusing book on a subject that would make many writers nervous. It describes some startling stupidity as well as some very sharp behaviour without forcing the point, and includes fierce assertions by followers on both sides. It is interesting to compare Brown’s well-documented narrative of Meher Baba’s life with the breathlessly reverential account on Wikipedia.

I strongly recommend paying attention to the book’s footnotes where some of the more knockabout material is buried. The best of these is a spirited exchange between Brown and a representative of Bhagavan Das, who is set on extracting hundreds of dollars for a conversation. It makes one realise that this character had for years probably only dealt with people all too ready to pay large sums in return for almost nothing. A lot of sharing of knowledge has taken place between the best minds of India and the best minds of the West, but those minds are not, to our considerable entertainment, represented much in Brown’s book.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in