The novel as a form is a fundamentally capitalist enterprise. It was invented at the same time as capitalism – Robinson Crusoe tots up his situation in the form of double-entry bookkeeping. Its interests dwell on the disparate and unequal natures of human beings and feed off rivalry, social transformation, moneymaking, profit and loss. No rigid feudal society has managed to create an effective school of novelists; and having once struggled through Cement, Fyodor Gladkov’s classic of socialist Soviet literature, I would say that systems dedicated to forcible equality also struggle.

Novels thrive during periods of brutal inequality, such as late Victorian Britain, but also when thrown into violent opposition to societies attempting to restrict personal enterprise. One of the most extravagant moments of fiction’s flourishing in our country came about in this mood of opposition after the second world war. With rationing continuing for years, taxation at levels approaching confiscation and a loss of all remembered excesses to a spirit of moral disapproval, the novel entered a glorious phase of opulence. Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited was one of the first; but if you come across a description of central heating in the fiction of this time, or an account of characters stuffing themselves with tournedos Rossini, you can be pretty sure of its appeal to a first readership shivering over a supper of snoek on toast.

Not the least of these marvellous monuments are the James Bond novels of Ian Fleming. Reading them, one has to remember the circumstances that made those gluttonous descriptions of meals and the tossing away of fortunes at the roulette table so agreeable. The young heroine of The Spy Who Loved Me buys a £10 tin of caviar to entertain her pals one evening (it would cost north of £10,000 now), and Bond and M’s dinner at M’s club in Moonraker surely passes all precedent for extravagance: smoked salmon, caviar, lamb cutlets, asparagus with béarnaise, a slice of pineapple, strawberries and finally a marrow bone, and some Benzedrine in a glass of champagne. (Bond goes on to cheat Drax out of tens of thousands at cards.) The excess is irresistible even now, and must have been overwhelming in 1953, when Bond’s career began with the publication of Casino Royale. I’m particularly fond of a moment in the film From Russia With Love when the camera freezes for what seems like minutes in front of the automatically opening door of a hotel lift, as though stunned with awe. The novels are full of such moments of fantasy countering the grey dullness of real existence.

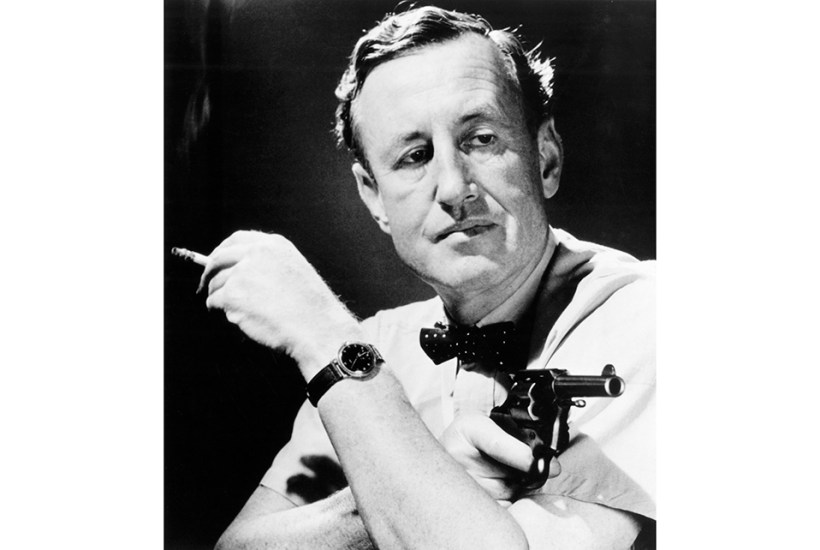

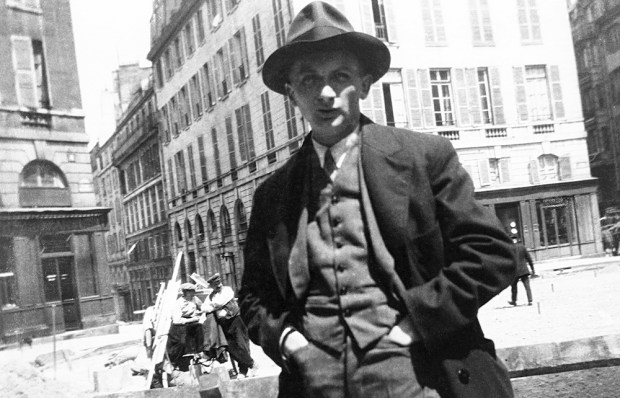

Fleming has been done before by biographers – often very well – and the reason is that he lived a life of extraordinary fullness and excitement long before Bond entered his head. Born in 1908, he was the grandson of one of the richest men in Europe, the son of a soldier killed in the Great War and of a famously impossible monster, Eve. (‘Augustus John never forgot her knickers’; and she was sued, aged 73, for sexual enticement of the 92-year-old Marquess of Winchester.) Ian’s elder brother Peter was a well-known writer from earliest youth and Ian himself was celebrated for his charm and personal bravery. He knew absolutely everybody and was one of those lotharios who fall just short of being a howling cad and is generally forgiven. (Not by everyone: he was threatened with being horsewhipped by the angry elder brother of a model, and a breach of promise suit had to be settled.)

A clue to his wide social appeal come early on in this book, as Nicholas Shakespeare cites firm opinions about Fleming from those who knew him, followed by the exact opposite from others equally well informed: ‘Ian adored money.’ ‘Money really wasn’t important to Ian.’ ‘He was most emphatically not a snob.’ ‘He was a real snob.’ That evidence of personal transformation suggested that two fates lay ahead: a career as a spy or one as a novelist. But for a long time he had to settle for being thinly disguised in other people’s novels – portraits which could fill a small anthology.

After working as a journalist, Fleming had an exceedingly successful war. Many contemporaries believed he was a mere pen-pusher who played at appearing important. Even now the truth can’t be fully revealed for security reasons, and in a brilliant chapter Shakespeare discusses just how many barriers stand in the way, before telling the story much more thoroughly than has been previously possible. Fleming certainly emerges as an exuberant sponsor of seemingly preposterous plans, such as the now famous Operation Mincemeat. (Much later, he enchanted J.F. Kennedy with a proposal for giving Fidel Castro a box of exploding cigars.) But what is clear is that he was in on some of the most significant episodes of the war and had to be kept away from direct action since his capture could have been catastrophic.

Also evident, astonishingly, is just how much in the Bond novels is based on events Fleming witnessed or personally engineered. I always thought the premise of Casino Royale totally preposterous – if a corrupt agent of the Soviets is trying to recoup his loss of their money at the roulette table, why not just sit back and enjoy the inevitable? – but it turns out to be grounded firmly in reality.

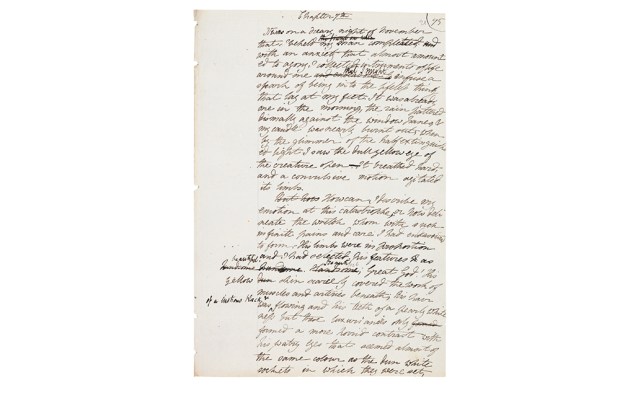

What forced the Bond novels into existence, surely, was a very expensive wife. Ann Fleming is a figure of unusual fascination – née Charteris and previously married to Lord Rothermere. Her passion for Ian was genuine, and based only in part on a shared taste for whipping and being whipped. But it was a challenge for her to move from the great Rothermere palaces to a house with a dining room that seated 12 at a pinch, and Goldeneye, a cement shack with a beautiful view in Jamaica. Money had to be made somehow, and one day Fleming sat down and typed the words: ‘The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning.’ The world would never be quite the same again.

This excellent biography is as worldly and clever as one could wish. Shakespeare is on top of the couple’s awe-inspiring social circle and lavish entertaining – one year, according to their cook, they held 180 luncheon parties and 220 dinners. This was also a rapidly changing world, when a Labour politician, George Brown, could be glimpsed sitting next to Ann, and Hugh Gaitskell, the Labour leader, became her lover. The author is also wonderfully adept at describing Ian’s disparate worlds of journalism, literature, espionage and physical danger.

Are the novels any good? Well they get rather worse as they go on, but the best of them have a directness and lack of shame, especially about Freudian-inflected topics, that will live forever. The films have widely eclipsed the books, as indeed they threatened to do in Fleming’s own mind – the tone of writing starts to change after the release of the movie of Doctor No in 1962 – but to turn back to the best of them is to experience a shock of a fantasy precisely delineated, even if, like Moonraker, it is entirely set in Kent. Other and greater spy novels would be written, but it’s still Fleming’s creation that comes indelibly to mind.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in