The number of students studying modern languages is plummeting, The Sunday Times says today. ‘The number of pupils studying German has fallen below 2,200 with French also on a downward trend — amid fears students are becoming little Englanders.’ It shows a graph suggesting, rather absurdly, that Brexit is linked to the drop. Really? Little Englanders because they don’t want to learn German? My hunch is that today’s young are more globally-minded than any generation that came before, and this is reflective of a Britain that voted in 2016 not to move away from Europe but to strengthen ties with the wider world.

When I was at school, we were told that Maastricht changes in 1992 would change our world: we were hearing of a European future – culturally and economically – which would be best exploited by those who spoke French, German, Spanish. Or all three. To my Cold War generation – and to me especially – this was welcome, even thrilling news. Technology, cheap travel and democratic trends certainly made the world (and Britain especially) more international – but the trends were more global than European. The idea of ‘Europe = Rest of the World’ soon became dated.

Today’s teenagers would struggle to be Little Englanders given that about a quarter of them will have an immigrant mum (in London, it’s just over half). Many will speak a foreign language at home (as my kids do) and it’s far more likely to be Polish, Panjabi or Urdu than French or German. So it is a more global world, rather than a more European one. Every tenth British child is brought up in a Muslim household. The Britain that young people grow up in is a fusion of ethnicities, languages and faith – and they’ll be comfortable with that.

Culturally, the young now live in a globalised digital world. Subtitling technology has come on now to the extent that Netflix commissions Korean dramas that are avidly consumed by people who don’t speak a word of the language but enjoy the daring, originality and photography that has made Korea a TV-drama superpower. The assumptions of terrestrial TV – that it all has to be in English – has also been proven small-minded by Netflix who show viewers enjoying Narcos or Call My Agent in the original languages.

My children’s generation look to South Korea in the way that I once did to America: as the cultural lodestar. The children turning down French and German in school listen to foreign-language music all the time, with Spotify bringing the world’s releases to their phones. In my day we had Joe Le Taxi and Falco and that was about it. Asia was, culturally, a terra incognita. When Korean band Black Pink came to Britain recently, they sold out the O2 with British fans.

Culturally, the young now live in a globalised digital world

The languages I learned (or tried to) were fun, but I’ll admit they’re of little practical help now. Google Translate has been revolutionary, opening up the foreign-language world at the touch of a button. I have subscriptions to Der Spiegel, Le Monde, SvD and Liberation and read them most days. The crude Google translation is enough. If my kids come across a notice in a foreign-language that they want to read, they take a picture – and let the smartphone technology translate. They grow up in a world more integrated and globalised than any that my generation could not have conceived of.

I’ll offer an example. A few days ago, my son Alex piped up with what it’s like to live in a New Delhi slum. I asked him how on earth he’d know, and he replied that he’s been comparing notes with another 15-year-old in that city who he had somehow met on Snapchat. Needless to say, they spoke in English – not so surprising given that there are twice as many English-speakers in India than in the UK. And that’s the other part: the global English-speaking population has vastly expanded. You don’t really need languages to take part in international conversations.

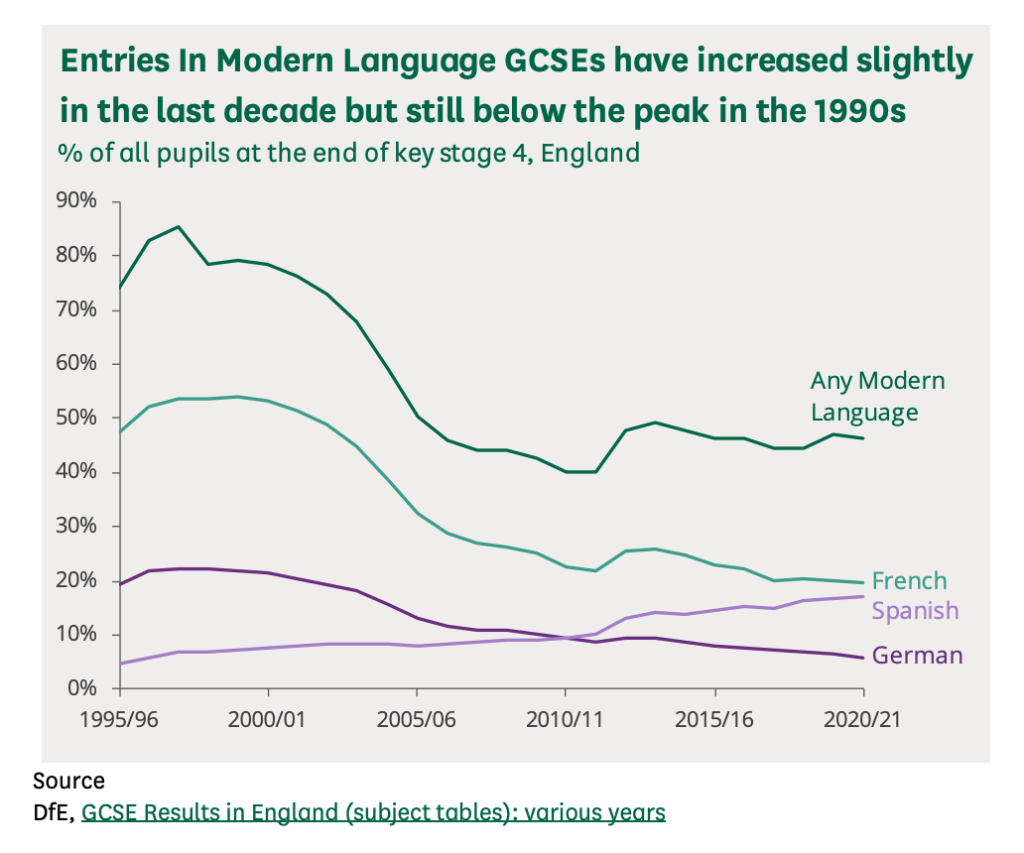

The Sunday Times story complains that British schools have fewer links with other European schools and that the exchange schemes are not so big now. But is that the same as saying the kids only care about England? The story (and its graph showing Brexit, French and German studies) does’t mention the fact that the number taking Mandarin GCSE has almost quadrupled in three years. Factor in Arabic and Urdu and the number of exams in ‘other modern languages’ is actually up 17 per cent in four years. In total, almost 50 per cent of GCSE students now study modern languages – up from about 40 per cent in the end of the Labour years. The proportion studying Spanish has actually doubled (to 17 per cent of all GCSE students) and it’s now firmly established as the leading language studied at A-Level.

The big drop in languages came not with Brexit but the mid-1990s when globalisation and technology started to speed up. But since 2010, the GCSE story has been one of revival in the study of modern languages, not decline – reflecting a country that is more, not less, interested and connected with the wider world. The story with A-Level languages is one of slower but steady decline, with no post-2010 revival. Brexit is irrelevant to both trends.

For professional purposes, there’s no substitute to learning a foreign language – and it’s a matter of huge concern that we have so few Mandarin speakers in the Civil Service. The UK is appallingly under-resourced for understanding China compared to how well we once did Russia. The Foreign Office has no end of people speaking in German and French: our schools did a good job at that. But understanding China – its language and culture – has suffered. I’d say that European parochialism played a part in that: confusing lack of interest in European languages with being a Little Englander. To young people today, Europe isn’t really foreign: it’s next door.

Professionally, I’m lucky to work in an office with so many people who understand languages. Freddy Gray is fluent in French, which brings with it a better understanding of its national debate. Cindy Yu has conducted Spectator TV interviews in her native Mandarin, Svitlana Morenets in her native Ukrainian and Lisa Haseldine in the Russian she studied at uni (she’s also fluent in German). They’ll all have the edge over anyone trying to understand these countries using Google translate.

The ability to interview in a foreign language gives the viewer a wider, better range of interviewee – ie, not just those who speak English. Netflix has proven audience appetite for foreign-language dramas: I’d like to think we may soon see UK television news do more foreign-language interviews and test the parochial assumption that audiences can only ever handle English. Feedback from Spectator TV audiences shows they appreciated the wider range of people brought by our foreign-language interviews.

There has been a lot of rot spoken about ‘Little England’ since the Brexit vote. It was a vote of a country that has always lifted its sights to more horizons and never really understood why Australians and Indians should be treated as second-class immigrants. Specialists aside, the skill needed to understand that world now is one of using translation tools that continue to evolve and open up new worlds. I suspect our young people now show more interest and engagement with the outside world than that that went before it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in