The genesis for our book Journeys across Roman Asia Minor was hatched in the autumn of 1973, when Sir Donald McCullin was a young man. He had been assigned by the Sunday Times to work with the writer Bruce Chatwin on a story that would take them from a murder in Marseille to the Aurès highlands of north-east Algeria. It was an emotionally gruelling journey and they rewarded themselves on the way back by stopping off to look at a solitary Roman ruin. No photographs were taken, but the memory of this place from all those years ago remained embedded in Don’s imagination. Three decades later, that seed bore fruit, as he undertook a series of visits to North Africa. I was lucky enough to accompany him on two of these trips, into western Libya and southern Algeria.

Don was locked into an affectionate dialogue with two of the pioneer photographers of this historical landscape: Maxime du Camp and Francis Frith. I heard from Don about the ‘startling clarity and precision’ that they had achieved with these first images of antiquity, their honest ‘factuality’, and how you could almost hear the crunch of their feet and taste the dust that had flicked up towards the camera lens some 150 years before.

Du Camp had travelled out to photograph the ancient monuments of Egypt between 1849 and 1851, in the company of another eminent Frenchman, Gustave Flaubert. Francis Frith was neither accompanied by some erudite companion nor endorsed by state funding. He was a self-willed, self-funded Anglo-Saxon who at the age of 33 dedicated himself to ‘the rage, the fury, the vexation of all kinds caused by my [obsession with] photography’.

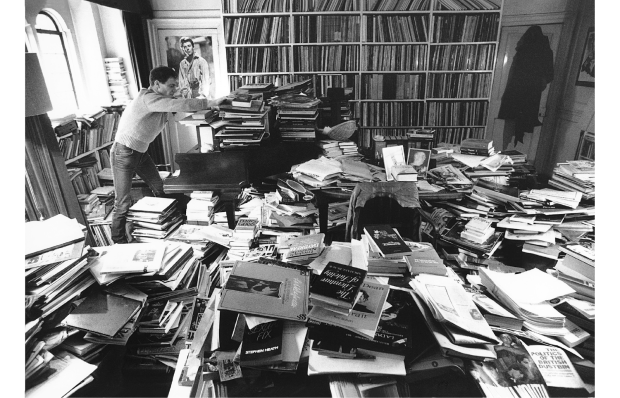

Before this, Frith had set himself up as a wholesale grocer and could have gone on to become a Lipton or a Sainsbury. Instead he used the small fortune he acquired to finance his obsession. He photographed Egypt and the Holy Land during three separate expeditions, in 1856, 1857 and 1858. This project would eventually fill 13 volumes of photographs. Don and I managed just one – Southern Frontiers: A Journey across the Roman Empire, published in 2010. It is the sort of book you might wish to be buried with, but when the last copy had been sold we toyed with trying to make it even better by plotting an expanded second edition. Don was particularly keen to photograph Cyrene, but travelling into eastern Libya at the time had been made difficult by a civil war. However, as this door closed another opened.

Despite being one of the world’s most well-travelled men, Don had never explored Turkey, though he had chronicled many wars fought near its frontiers. I was able to assure him that the country would equal what he had seen of Roman North Africa. I was also able to tell him that, despite exploring the ruins of Turkey for the past 30 years with what my family considers to be excessive zeal, there were a large number of ruins I was still keen to track down.

There was one hurdle left: Don’s reputation as the world’s foremost war photographer. Such fame can open many doors, but it can have the reverse effect on frontier police and tourist visas, especially when he takes his camera bags. Moreover, I have travelled enough with Don to know that, although he is one of nature’s true gentlemen, his manners go into reverse with any man in uniform, who to him is like a red rag to a bull. So we decided there should be no sneaking about among the bushes with this project. We were workers, not tourists, and we would need formal permission to use tripods in museum galleries.

Before our first meeting at the Turkish embassy I was slightly nervous as to how it would go. But I should not have worried. The ambassador had been to Don’s retrospective at the Tate and had been moved that among all the many wars and massacres recorded, there had been space to testify to the sufferings of an ordinary Turkish family in Cyprus in 1963. The Turks get a lot of respect as a martial nation but they do not receive much empathy. The ambassador had not forgotten what he had seen. Over lunch I heard him assure Don that any photographer was free to travel to Turkey and click away at every Roman ruin to their heart’s content – but that Don would be particularly welcome.

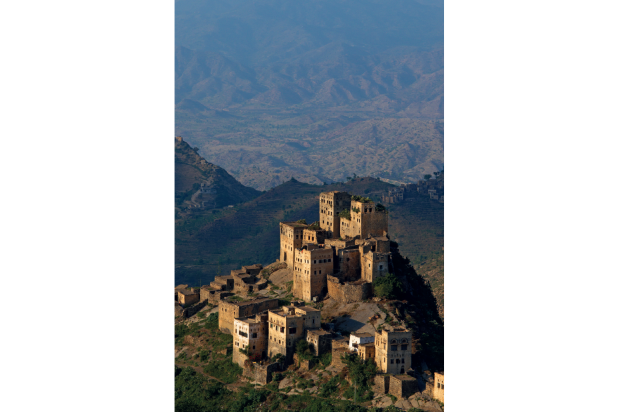

We undertook three separate journeys across western Turkey, beginning in 2019 and ending last year, and made good use of the various Covid lockdown periods to travel the moment we were permitted to, but before the tourist crowds returned. We had some very simple ground rules. We would concentrate on the relics of the Roman Empire but also include what the Romans had repaired and used from previous ages. We would stay as close as possible to any ancient city in whatever accommodation we could find, in order to be up before the dawn light and to be able to linger on through into the dusk. We would make no plans that could not be changed should we happen upon anything beautiful on the road. All of this was made possible by two travelling companions: Ahmet Komurkıran at the wheel and Monica Fritz on her iPhone. Monica was our updated version of a traditional dragoman guide, busily plotting routes and unearthing interesting restaurants.

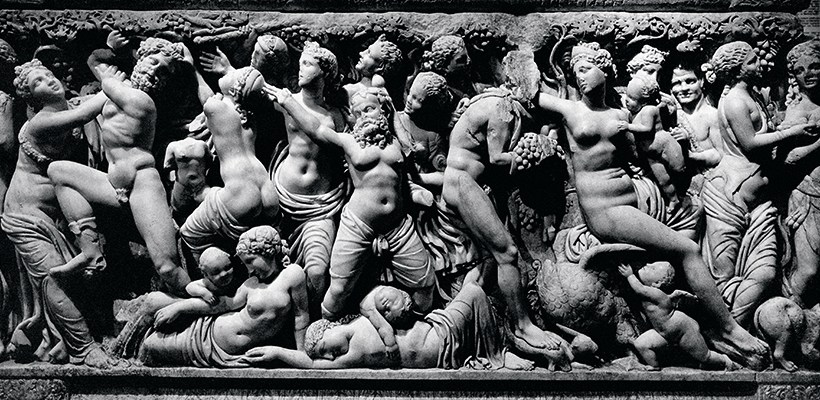

We focused on the Roman period, offering as it does a shared memory link with all Mediterranean and European cultures and, unless you have the immense good fortune to be born Italian, almost divorced from any sense of patriotism. It was also vital to draw a line somewhere, as Turkey is so full of monuments and the homeland of so many successive empires that we would otherwise submerge ourselves entirely in the richness of the landscape’s history.

When I last met Don, we rather tortured ourselves by unfolding an ancient map and tracing how little of Roman Turkey we had covered. Bithynia we just scratched the surface of; the provinces of Cappadocia, Cilicia, Pontus and Galatia were left completely untouched, let alone the Roman military frontier posts along the Euphrates valley. I then folded the map so that it framed western Anatolia alone, and with lights sparkling in two pairs of eyes, we thanked our lucky stars for what we had seen.

The ‘Asia Minor’ in the title of our book is an important marker. The Roman province of Asia was only one of the seven Roman provinces within the modern frontiers of Turkey. But it is an elusive name. To us it meant the western province of Roman Turkey, but we later found out that it came into common use only through early Christian writers tracking the journeys of St Paul, and was never an official term during the classical age of the Empire. But we were reassured when a scholar informed us that the word Asia has always meant different things at different times: starting off as the Hittite homeland (Aswiya) in Anatolia before it grew and embraced all of their Bronze Age empire, which stretched across Turkey. Now it embraces a vast continent. So we have stuck to that romantic resonance of Roman Asia Minor, a literary province of the mind.

It was a continual theme of all three of our journeys to chuckle over the way any single city that we explored in Asia Minor held more elegance and enchantment than all the surviving elements of Roman Britain put together. Meanwhile, the cumulative energy of all those Roman bridges, fountains, embankments, gates, walls and tombs we discovered in the countryside – many of them still standing and in use where they had been placed 2,000 years ago – told another story: one of continuity. Our journeys taught us, too, that if the European Union is in any way inspired or modelled on the achievements of the Roman Empire it is marvellously absurd to have excluded the glories of Asia Minor.

Don and I both revere the classical past to an almost embarrassing degree, but we became aware that today’s Turks, in their everyday habits – bathing, eating, relaxing at home – are part of this living tradition. Students of the classical world will glean more from bathing in an Ottoman hamam and then sitting in a Turkish meyhane watching the theatrical arrival of tempting small platters, than from any number of university lectures.

It was my self-appointed task to get Don to the Roman ruins within Asia Minor that I thought would interest him most in terms of their size, shape, historical importance and state of preservation. We also needed to be at our chosen sites with time to spare, to capture the light of dawn and dusk, with clouds as a bonus. Don was born in 1935, but any age he might wear is shed at these critical hours, when he lives up to his confession: ‘I have just one addiction – photography.’

During our journeys I have noticed how he is inspired by an internal aesthetic, which is attuned to the authenticity of the monument. His camera bag would remain buttoned if he observed too much restoration, or any sign of an excavation trench, or thought we were trespassing on what had once been a domestic space – unless I begged him, saying that it had been mentioned by Homer or walked upon by Aristotle, which is how we fell in love with the Temple of Apollo Smintheus and the Temple of Athena at Assos.

What especially seemed to absorb him was something that had once been very fine but had been weathered by time, that had endured terrifying periods of conflict but had miraculously survived with its spirit intact after centuries of adversity. At times it was as if he was catching a glimpse of his own soul, weathered in ancient stone.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in