If there’s one thing the internet knows, it’s that cats sell. The Scottish painter Elizabeth Blackadder, who died in 2021 at the age of 89, knew it too. Her sinuous, characterful cat pictures, watercolours mostly but also oils and prints, helped cement her place as the nation’s favourite painter. She was an establishment favourite too, becoming the first woman to be elected to both the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Academy in London. In 1995, her cats adorned a set of Royal Mail stamps and, in 2001, she became the first woman to be appointed as Her Majesty’s Painter and Limner, a position unique to the Royal Household of Scotland, previously occupied by the likes of Henry Raeburn, David Wilkie and David Young Cameron. In 2012 she accepted a commission to paint the then first minister Alex Salmond’s Christmas card, following in the footsteps of Alasdair Gray and Jack Vettriano.

No wonder some of her fellow artists occasionally looked enviously upon her success and, longingly eyeing her more muscly early work, made dark mutterings about selling out. But it’s daft to dismiss Blackadder as the Vettriano of cats just because of all the calendars and tea towels flying out of gallery gift shops. She didn’t sell out, though her shows frequently did. Her trajectory from semi-abstract landscape painting, heavily influenced by her Edinburgh College of Art tutor William Gillies, to the structured foregrounding of cats and flowers is the journey of an inquisitive artist exploring the world around them and gradually sloughing off the bits that no longer captivate.

A new retrospective exhibition at the Scottish Gallery, where Blackadder exhibited for more than half a century, explores this evolution across more than 60 works, all for sale, alongside a newly commissioned tapestry that celebrates the artist’s long history of creative collaboration with Edinburgh’s Dovecot Studios. The show treads a lifetime of painting, from the thickly impastoed oils of the early 1960s to the sparsely spaced still lives of her final years which prove she never lost her inventiveness, or her eye for colour, pattern and detail.

Of those later works, ‘Japanese Plate and Wooden Fruit’, from 2009, typifies Blackadder’s signature ‘table top’ compositions, with the pictorial space flattened on to a single plane, abstracting the chosen objects into a satisfying arrangement driven by form and colour. Subdued purples and greys structure the spaces between the vividly sketched out objects in a way that recurs throughout her work; sombre backgrounds emphasising the pop of the main event. We see it in one of the earliest pieces, ‘Still Life with Pineapple’ (1963), in which Blackadder handles the paint almost like Joan Eardley, pushing it roughly around the canvas as she bullies it into a muddy congregation of abstracted forms. Only the pineapple, the focus of the painting, leaps out, vivid in its nubbly orange body and hostile green leaves.

‘Reflection in a Dark Pool’ (1993) does the same thing. The two-metre canvas is mostly occupied by bisecting black rectangles, but lurking within them are scrawls of colour tracing out lily pads, glistening light and the quick darts of electric orange carp. Two corners coloured by sketchy green leaves anchor the composition and emphasise the blasts of orange. It’s the kind of painting that gets painters excited.

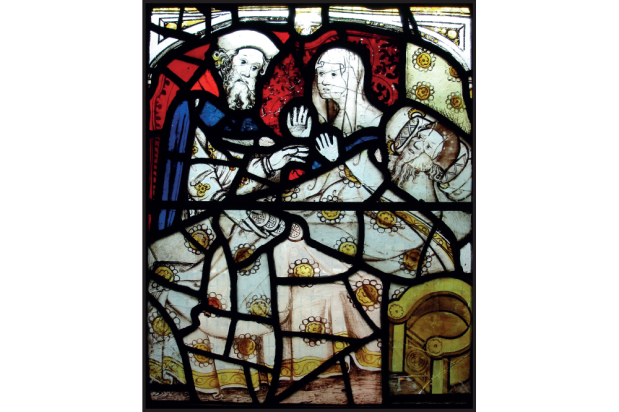

And then, when you look again at the cats and the flowers, you see the same tricks. ‘Rosie, Coco and Orchids’ (1984) (see above) combines it all, a wandering watercolour that is deceptively organised. Two cats float in a strange liminal non-space, both behind and in front of the orchids that snake up the paper. Patterned scarves, a recurrent Blackadder motif, further divide the space, weighting the foot of the picture with texture and colour. Elsewhere, the flower paintings leap out, not so much scientifically rigorous in their attention to botanical detail as expressive and devoted to colour. Irises flop all over the place, sucking watercolour pigment into fathomless pools on their petals, strelitzia (1989) puncture the paper with their vicious orange blooms while an offset vase of gladioli (2010) maintains Blackadder’s mastery of colour, balancing an orchestra of depthless purples, reds and oranges, invigorated by the smallest, clearest cuts of blue.

Blackadder and her husband John Houston, the celebrated landscape painter who died in 2008, left a bequest worth more than £7 million to the Royal Scottish Academy with instructions on how it should be used to help future generations of Scottish artists at all stages of their careers. The RSA is marking this with its own exhibition of work and archive material from Blackadder and Houston (29 July – 10 September), so fans will be spoilt for choice in Edinburgh this summer. But anyone wishing to snap up one of the several sleek cats coiling through the Scottish Gallery will have to move fast. They’re sure to sell out, and rightly so.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in