Another day, another spat between Warsaw and Brussels. This time, Poland has declined to participate in the European Union’s latest plan to relocate migrants and asylum seekers within the bloc, with countries who refuse being expected to pay €20,000 per refugee. Hungary has also voted against the pact, while Malta, Lithuania, Slovakia, Bulgaria have quietly abstained.

On 15 June, the Polish parliament (the Sejm) went further and passed a resolution opposing the plan, with the ruling conservative Law and Justice party (PiS) announcing a national referendum on the matter. The referendum will take place on the same day as the general election in either October or November this year.

‘The Sejm of the Republic of Poland,’ the resolution reads, ‘expresses its strong opposition to the attempt to introduce mechanisms for the forced relocation of illegal economic migrants at the European Union level… We do not agree that the Polish state should bear the social and financial costs of the bad decisions of another European Union member state. The “open door” policy, which was pushed through by Germany, violating the treaties, turned out to be a big mistake.’

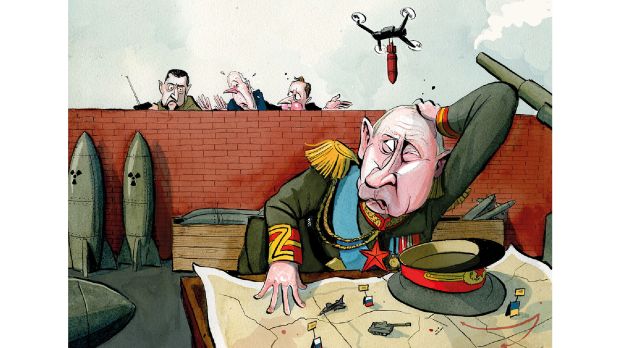

The resolution also points out that Poland has allowed close to seven million Ukrainian refugees into the country, 1.5 million of whom have stayed, since Russia’s invasion. Why, they ask, should they take in more?

Meanwhile in Brussels, EU officials have accused PiS of misrepresenting the migration pact, saying no country will be forced to receive relocated migrants and that Poland would not have to pay ‘solidarity payments’ to countries that house them because it has taken in so many Ukrainian refugees. Commissioner Ylva Johansson said: ‘Poland’s criticism of the EU’s planned migration pact is incomprehensible and untrue.’ So what is really going on?

PiS have always had a fraught relationship with the EU, which dislikes the party’s ‘populism’, taking it to task on policies from its almost total ban on abortion to its supposed lack of democracy. To date Warsaw owes Brussels €237 million in fines which it has refused to pay, saying that Brussels has no right to meddle in Poland’s domestic affairs.

Brussels has also been on Poland’s back for years, not just the past few weeks, about taking more immigrants. In 2020, the European Court of Justice ruled that Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic had breached their obligations under European law by refusing to take in refugees. At the time, the Polish national broadcaster Telewizja Polska reported that the ECJ had decided ‘ideology is more important than the safety… of inhabitants of the community’.

Given this, PiS’s disinclination to negotiate or engage with EU chiefs is unsurprising, but critics of the Polish government also feel that it suits PiS to be at odds with the EU and that the party uses this bad blood to galvanise feelings of national pride and so boost its popularity among the electorate.

Admitting to having voted for PiS in Poland is a bit like admitting to having voted for Brexit in the UK. Most people will deny having done so, yet somehow the votes in favour are cast in their multitudes, and clearly not just by uneducated, religious, rural simpletons, as the opposition parties would like us to think. In the case of PiS, the party has been in power for two terms. ‘The people running PiS – Ryszard Terlecki, Jaroslaw Kaczynski – are extremely clever politically, they sense the pulse of the nation,’ says Matthew Kielanowski, an immigration lawyer who advises governments on Polish affairs. It also helps that Poland appears to be thriving economically after those two terms, with its GDP per capita on course to overtake Britain’s by 2040.

Moments of genius which have infuriated their opponents over the years have included the decision to give every household with children in Poland 500 zlotys (about £150) a month per child. While this scheme was introduced with a view to boosting birth rates, it was clearly very gratefully received by this stereotypical Catholic, country–dwelling voter, who views Kaczynski as a benevolent father figure. Other successful tactics include feeding the Polish people’s already strong sense of victimhood, a result of centuries of foreign occupation, which includes telling them that they are being exploited by Brussels. It is true that this demo-graphic also particularly fears immigrants from other cultures and religions. But they are not the only ones who are against the EU imposing migrant quotas on the nation.

The more worldly Pole – not such a rare beast these days – has been to France and Germany, countries which they know are ravaged by gang violence caused by mass immigration, along with the likes of Belgium and Sweden. ‘It’s a rare night in Stockholm that passes without some violent event,’ wrote Jonathan Miller in last week’s Spectator. In Poland, however, 88 per cent of people feel safe on the streets, according to a national poll by CBOS; crime levels are extremely low and gangs do not exist. According to the same polling company, Poles feel safer now than they did before PiS came into power in 2015.

The more worldly Pole has also probably played host to a Ukrainian refugee at some point in the past year, and there is the growing sense in Poland that this enormous humanitarian effort is being taken for granted by EU powers who the government says have been very slow to help financially.

Last year, Poland issued almost one million first residence permits to immigrants from outside the European Union, more than any other EU member state. It is the fifth year in a row that Poland has topped the list. That Poland prefers to decide who it admits rather than being dictated to by the EU seems fairly sensible. While it does allow in a small number of people from North African countries, it does so on its own terms. Admitting Ukrainians was unproblematic: they are their neighbours, Christians and speak a similar language – many of those from the west of Ukraine even speak Polish – and so there was never any question that they would assimilate with ease.

Poles are also acutely aware that a war is raging close to their borders and the last thing they want at the moment is more trouble. The threat of the imposition of this migrant re-location scheme comes at a fraught time, and Poles are highly likely to vote against it in large numbers in the referendum.

Of course, this all seems to come as a great boon to PiS, who until now feared they may not win a third term. The past few years have not be plain sailing for them – a failing healthcare system following the pandemic, poor relations with Germany and Russia, the war in Ukraine – and the expectation has been that they will be forced into coalition with the so-called ‘far right’ Konfederacja party (they are unlikely to lose power entirely because the opposition party Platforma Obywatelska is shambolic and divided by warring factions).

The referendum, however, will inevitably boost turnout, which is likely to go in PiS’s favour. ‘It seems that Brussels yet again, with its pressure on Poland, may have presented the right-wing government with a pre-election gift,’ says George Byczynski, conservative commentator and adviser to the all-party parliamentary group on Poland.

There are those, like Kielanowski, who believe that if Poland were to present its case calmly to the European Commission, it would be officially excused from the relocation scheme. It also might get the money it wants for taking in the Ukrainians. ‘The biggest problem is the Polish inability to persuade, argue and negotiate on a level in Brussels,’ he explains. But clearly in PiS’s case, not getting on with the EU suits its agenda. By not wasting time on diplomacy, the party is free to concentrate its efforts on electoral tactics at home.

And ultimately, what can Brussels do if Poland flatly refuses to comply or even negotiate? Apart from getting very annoyed, not very much, says Kielanowski. ‘Nothing in the EU can be enforced. They can think of some penalties, but if they fine Poland for this, Poland will start fighting it in the European court, which will take years, and eventually Poland may win.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in