P-p-pick up a pebble. Feel its weight in your palm. Roll it over under your thumb. Any good? Not sure? Shuck it back on the shingle. Plenty of fish in the sea and more pebbles still on the shore.

In The Pebbles on the Beach: A Spotter’s Guide, Clarence Ellis, pebble-spotter par excellence, opens with the words: ‘Most people collect something or other: stamps, butterflies, beetles, moths, dried and pressed wildflowers, old snuffboxes, china dogs and so forth. A few eccentrics even collect bus tickets! But collectors of pebbles are rare.’ We are not talking about the common or garden or indeed communal garden collector of pebbles – the sort with a wheelbarrow and a trowel. A true pebble-spotter does not make off with cartloads to resurface the driveway. ‘Let us hasten to add,’ Mr Ellis hastens to add, ‘that we mean discriminating collectors.’

Men such as Jim Ede, founder of Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, who made his house a home for modern art, sculpture and pebbles. ‘The Louvre of the Pebble,’ the poet Ian Hamilton Finlay called it. Ede was particular about pebbles. ‘You find a perfect pebble once in a generation,’ he proclaimed. At Kettle’s Yard he assembled a spiral of nearly perfectly spherical pebbles. When a friend of a friend sent him a pebble she thought would do, he sent his regrets: ‘Mighty kind,’ but ‘I’m an awfully difficult pebble fiend’. The pleasure wasn’t in the possession so much as the spotting, the stooping, the picking up, the polishing with a pocket handkerchief.

In the introduction to his biography of Augustus John, Michael Holroyd raises the question of ‘invasion’ – the ways a subject gets under a biographer’s skin. While writing a biography of Ede, Ways of Life: Jim Ede and the Kettle’s Yard Artists, I became a pebble fiend and an awfully difficult one at that. And so, when we find ourselves on the coast and my husband looks out to the far horizon and breathes the salty air and says ‘Just look at that sea!’, I grunt and go back to squinting at the beach beneath my feet.

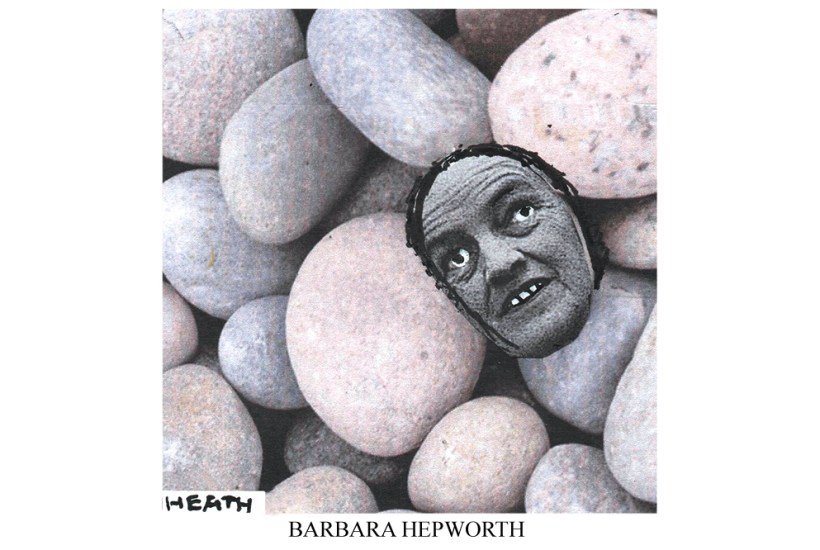

Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore did their best to better pebbles with their sculpture, knowing it was a game that they could only lose. ‘Many people select a stone or a pebble to carry for the day,’ said Hepworth. “The weight and form and texture felt in our hands relates us to the past and gives us a sense of a universal force. The beautifully shaped stone washed up by the sea is a symbol of continuity, a silent image of our desire for survival, peace or security.’ Or just a summer holiday souvenir. Whitstable – 2014. Hastings – 2017. Mousehole – 2023.

If you’re lucky, you might find a hag stone: a pebble with a hole worn through it, otherwise known as an adder stone and thought to ward off nightmares, witches and snakebites. A friend finds carnelians on his nearest stretch of Norfolk sand. ‘Best,’ he says, ‘on a sunny winter’s day. You need low light to catch the translucence’. But let’s stop there. We are not lapidaries, nor are we panning for gold. We are pebble-spotters, plain and simple. But there is no prize so precious or semi-precious as a practically perfect pebble picked up on a public beach.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in