The Reserve Bank of Australia (‘RBA’) has raised the cash rate – the rate that banks pay to borrow funds from other banks in the money market – to 4.1 per cent. It is the 12th rate hike since May 2022 and the highest it has been for eleven years. This latest increase in the cash rate will undoubtedly cause banks to increase their variable interest rates, thereby resulting in mortgagors having to pay more for their loans – a selective virtual tax on one part of the community already under financial stress.

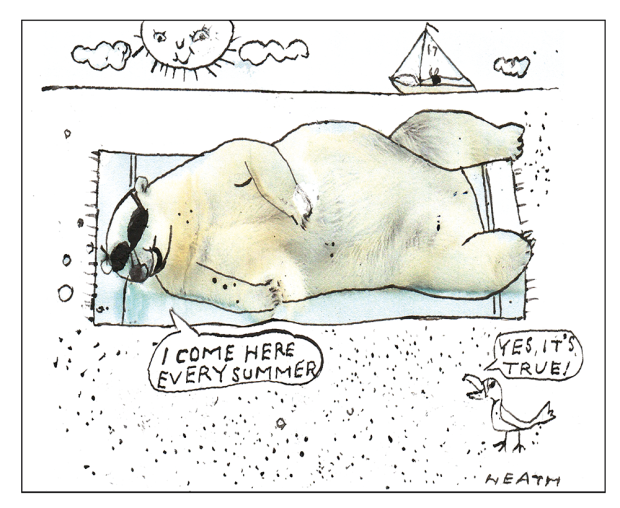

The Governor of the RBA, Philip Lowe, in an address to the Morgan Stanley summit on June 7, suggested that Australians should work more and spend less to cope with rising interest rates. ‘If people can cut back spending, or in some cases find additional hours of work, that would put them back into a positive cash flow position,’ the Governor told the summit.

As expected, the RBA Governor was criticised for his ‘out-of-touch’ comments and some critics bluntly condemned the increase in the cash rate. For example, journalist Amy Remeikis said: ‘Instead of a CEO sleep out, we should just put … the RBA board and big business leaders on the average Australian wage for six months … and get them to show us how it works … in this economy.’

Essentially, the RBA uses higher interest rates as the strategy to combat inflation, now standing at nearly 7 per cent. However, although there have been increases in interest rates throughout the year and last year, the inflation rate remains stubbornly high. That fact, by itself, shows that increased interest rates are not the magic solution to a persistent problem. It certainly defies the optimistic predictions contained in the Treasurer’s 2023 Budget, which claims that ‘inflation has peaked … expected to fall to 3¼ per cent in 2023–24 and return to the target band in 2024–25’.

In blindly pursuing the Net Zero diktats of the well-named Conferences Of Parties (‘COP’) – COP 26 was another jolly overseas trip for tens of thousands of happy travellers – the government has invested heavily in imported solar panels and wind turbines, driving the cost of power to levels that have forced productive companies to either close or relocate offshore with consequent job losses. Also, to combat the Covid pandemic, Australia has been borrowing virtual money at usurious interest rates from offshore banks with no real asset backing.

To that purpose, it became necessary to ‘print’ money. But the ready availability of money increases demand for consumer goods, thereby reducing their overall obtainability and increasing the price at which they are sold to consumers. In this context, Winston Churchill, commenting upon this phenomenon, allegedly stated: ‘I contend that for a nation to tax itself into prosperity is like a man standing in a bucket and trying to lift himself up by the handle.’ Inflation is taxation by stealth.

The Budget’s target of an inflation rate of 3¼ per cent in 2023–24 is unrealistic, especially in view of the spiraling cost of electricity, which determines the price of consumer goods and makes our products uncompetitive in the world market. Since the release of the Budget, the Australian Energy Regulator (‘AER’) confirmed that electricity prices would increase by between 20 and 25 per cent from July 1. Such an increase will dreadfully impact on the Australian economy, once built on the rock of cheap, reliable power. The energy grid does not need costly and unnecessary duplication to serve unreliable, dilute energy sources of wind and sun, that weaken and render uneconomic the existing low-cost and reliable coal-fired power stations. These will still be required to do the heavy lifting to back-up power supply when the wind does not blow, and the sun does not shine.

What is interesting is the seeming inability of today’s leaders to learn from the mistakes made in the past, especially in other periods when there was high inflation. For example, in the third century AD – a time of high inflation – the Roman Empire financed budget deficits by debasing the currency, using coins of cheaper metal, and reducing their size while maintaining their face value. Today, we print paper money or use digital virtual credits. Splashing the cash on the taxpayer’s credit card may buy votes, but those who inherit the accumulated debt will have little cause to thank their forebears. Uncontrolled government spending nurtures an inflationary spiral because, in extending the availability of credit, more will be spent by consumers seeking increasingly scarce consumer goods at higher prices. It may stimulate the economy, but only temporarily. Last year, Argentina, another country rich in natural and human resources, saw inflation spiral from over 50 per cent to over 100 per cent.

In 301 AD, the Roman Emperor, Diocletian, issued the Edict on Prices. The Edict provided for the setting of maximum prices for all-important consumer goods, services as well as wages. However, the Edict was spectacularly unsuccessful and when Diocletian resigned and retreated to his newly built palace in what is now Split, Croatia in 305 AD, the Edict was for all practical purposes a dead letter.

An educational, yet entertaining, 16 mm film about solving the case of Inflation, The Inflation File, was produced in the 1970s and is recalled only because it was so memorably incisive. In a brilliant spoof, an American ‘Private Eye’ detective (called a ‘Gumshoe’ in those days when these sneakers were popular) was assigned to solve the case of ‘Inflation’. The Private Eye had flashbacks of his ancestors, who were also working on the same case during historic episodes of inflation, starting with the Diocletian Edict on Prices. The Roman Private Eye, dressed in a toga, comes across Diocletian, dressed in his toga, lolling on a sofa, being fed peeled grapes by beautiful women, and clipping the edges off gold drachmas, he tossed the offcuts into one bucket and the physically devalued coin into another. The Private Eye queries: ‘Won’t that cause inflation?’ Emperor Diocletian says imperiously: ‘Not for me – I spend them first.’ Debasement of the currency, and printing fiat money, or creating too much digital credit, is the very essence of inflation.

It also constantly leads to demands for higher wages – a top priority of the Labor government. But higher wages exacerbate, and do not decrease, inflationary forces, now prevalent in our economy. Advice given by the RBA Governor – to be more productive and spend less – cannot solve the case of Inflation.

Inflation is a recurring major economic problem because Australia is not effectively mobilising its vast natural resources, while its human resources are drowning in a swamp of rules and regulations that inhibit productivity.

In Matthew 7:24-27, we find the following admonition:

The rain came down, the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat on that house; and it didn’t fall, for it was founded on the rock. … a foolish man … built his house on the sand. The rain came down, the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat on that house; and it fell — and great was its fall.

Matthew’s aphorism is a reminder that the prosperity of Australia was built on an organic rock, coal, that provided muscle power over and beyond manpower. Until the advent of the steam engine, horsepower provided improved productivity, and even today the powerful engines on which we rely are measured in the number of horses they replace. An 800 HP tractor produces much less manure than the same number of horses, and the invention of the motor car averted the horse manure crisis in London and New York at the end of the 19th century when the solid emissions of 100,000 horses in the streets of those cities became overpowering. Coal replaced the horse and capricious power of wind and water (windmills and water wheels), but this foundational rock has been undermined by the Federal Budget delivered on Tuesday, May 9, 2023. The Budget fails to confront Australia’s major economic issues, inflation, energy security, government debt, and a malfunctioning tax system that has its focus on the redistribution of wealth while inhibiting its creation.

Even a perfunctory reading of the Budget reveals the extent of the structural damage hidden behind successive layers of whitewash. The Budget is based on the shifting sands of popular opinion as against the rock of pure and applied science. A rock that is being undermined as consensus is now mistaken for scientific debate.

The cost of energy is reflected in all commodities. The closure of the Liddell 1,000 MW power station that supplied low-cost reliable power 7,000 to 8,000 hours per year was followed by the news that wholesale electricity prices in New South Wales surged by 80 per cent in the first five days following closure. Liddell is to be replaced with a 500 MW battery with four hours of stored energy that must first be generated from somewhere else. When the battery runs flat, the lights go out. Hence, a Budget based on 3¼ per cent inflation lacks any credibility.

The Budget papers also state: ‘The government is laying the foundations for a stronger, more secure economy by investing a further $4.0 billion in our plan to become a renewable energy superpower.’ The only way to transition to limitless nuclear energy on which any future superpower can be built is to continue to utilise the relatively small amounts of vast coal deposits we now use and which are to all intents and purposes unlimited at our current rates of usage. There is a cogent scientific argument that atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide are at historic lows, and that levels of 1,000–2,000 ppm are not only beneficial to all forms of life, but do not interrupt the planetary cycles that control the climate.

Carbon credits, making money by trading thin air, is again making fortunes for carbon cowboys; farmers will be paid to lock up once productive pastures, and another layer of bureaucracy is being added to a house of cards built on the false premise that already low levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere should be reduced with energy-hungry, egregiously named, carbon-capture-and-storage schemes.

Life on Planet Earth flourishes when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are between 1,000–3,000 ppm. Such levels have not caused the planet to overheat in the past. Plant life is extinguished when carbon dioxide levels fall below 150 ppm. Commercial life, as we know it today, will be similarly smothered when a new overseeing bureaucratic layer springs into action. Establishing a Net Zero Authority is another nail in the coffin of sanity and further undermines the solid rock upon which Australia has been built. The Budget foreshadows another raft of stifling rules and regulations requiring an army of public servants to police and obstruct productive activities.

If Australia wants to tame the Inflation monster and is to flourish and prosper in the future, politicians and policymakers should be reminded of Matthew’s eternal message, ‘A house built on rock ….’

Gabriël A. Moens AM is an emeritus professor of law at the University of Queensland and served as pro vice-chancellor and dean at Murdoch University. In 2003, Moens was awarded the Australian Centenary Medal by the prime minister for services to education.

John McRobert is a civil engineer with over 60 years’ experience in the design, construction and maintenance of major infrastructure, and the study of extreme natural events on man-made structures. He founded CopyRight Publishing in 1987 to facilitate informed debate, publishing over 200 books, including seminal volumes by geologists and engineers on major Earth seismic events.