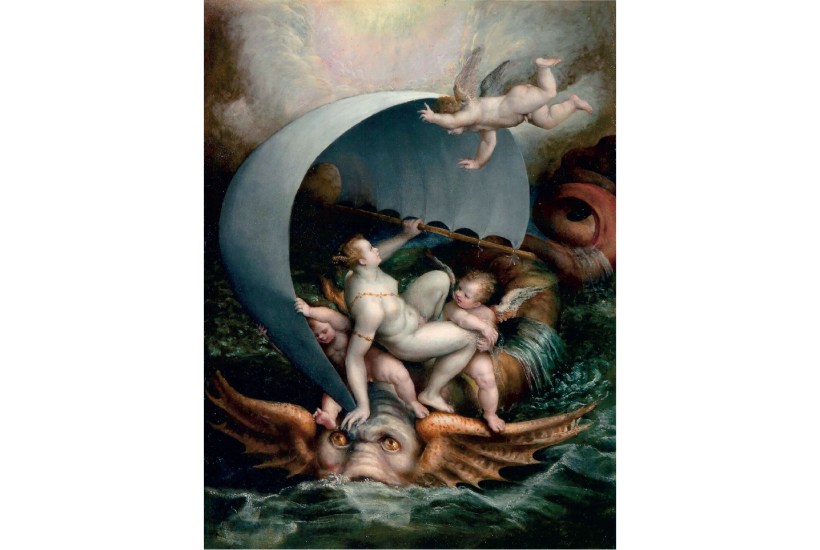

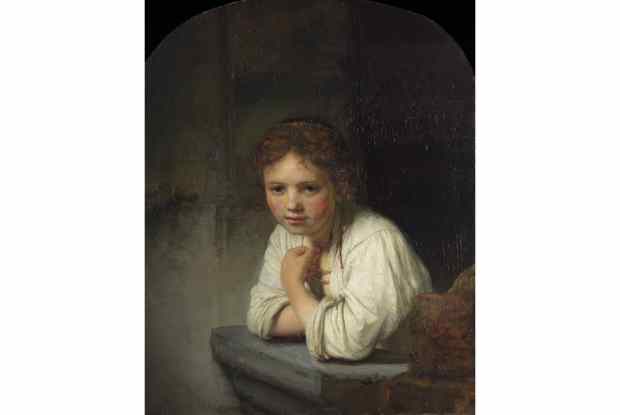

Reviewing the Prado’s joint exhibition of Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana in the Art Newspaper three years ago, Brian Allen pronounced it well worth seeing but predicted that each of these pioneering 16th-century women artists ‘would wither in the spotlight of her own retrospective’. Was he right? In its new monographic exhibition devoted to Fontana, the National Gallery of Ireland puts his waspish prediction to the test.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in