The hubbub about Boris Johnson is blocking the view. He is, of course, an easy and undemanding topic of conversation. His behaviour is, of course, unedifying. His unsuitability for office is beyond question. And his capacity to horrify, amuse, disgust or worry us appears limitless. So here we all are again, talking about ‘Boris’. And who am I to complain? I’ve been writing all this for at least a decade, the well of my indignation never runs dry, and – frankly – Johnson has put food on my and many a fellow commentator’s table for almost as long as we can remember. We’d miss him.

Yet, quietly and almost without our noticing, we and perhaps millions of other citizens who take an interest in the world of Westminster and beyond have allowed our attention to slip away from something that has never been more important: politics. Not showbusiness – Johnson is showbusiness – but politics. And, more specifically for Conservative-minded people (and I’m still one), the meaning and purpose of Conservatism in the 21st century.

How is it that a new Tory prime minister who strikes me as one of the more profoundly Conservative of our party leaders since Lord Salisbury (‘Reform? Aren’t things bad enough already?’) can find himself denounced by elements on the right – the right – of this parliamentary Conservative party, as betraying ‘Tory principles’?

What are Tory principles? It is said of common ailments that the more suggested cures one encounters, the less likely there is to be a cure. Likewise, and with the same implication, books on the meaning of Conservatism are legion: eminent historians, academics and political scientists keep trying. But the fact that attempting a comprehensive and internally consistent critique of Conservatism is a mug’s game does not mean (as cynical journalists like to claim) that this is a party that believes only in power, and whatever it takes to get it and keep it.

Nobody who has belonged to and worked for the Tory party for as long as I did can escape the inchoate but strong impression that this is a party with ancient and abiding instincts. Toryism has a nature, and though Tories do not always act in their natures, they tend to. To describe this nature is not so much to outline a political manifesto as to describe a very recognisable human type.

Your typical Conservative prefers the status quo to the unknown. He or she has a strong streak of native caution. He or she, though no slave to tradition, takes it as their starting position that things are as they are for a reason, and if you want to change them, you’ll need to find a better reason. Otherwise, let well enough alone. In the long history of social change, Conservatives have tended to drag their feet, but not to obstruct at all costs nor, once the change is made and embedded, to swim too hard against the tide.

This innate prudence extends particularly to the matter of financial discipline. Tories care about cost, and care about the good housekeeping that keeps costs down. They are not given to economic adventures. They are distrustful of revolutionary ideas for managing a national economy. This includes radical right-wing schemes as well as the usual left-wing ones. I cannot say that your typical Tory is a zealot for the theory of free-market competition – he or she inclines to a quiet life – but their belief in self-reliance, self-help, hard work (and retaining the harvests of hard work) makes them staunch if often untutored devotees of essentially capitalist economics, and sceptics about happy but expensive schemes for public welfare. Individualism, and family ties, do have a firmer hold on the Conservative imagination than any broad concept of ‘society’ – of which Tories are vaguely suspicious. Mrs Thatcher was right about that.

Such, then, is my idea of a Conservative. I certainly do not say Brexit necessarily offended any of these instincts – you could as a Tory believe the costs of EU membership outweighed the benefits. But you would believe that not as an article of faith but as the bottom line of a calculation. The spirit of ‘Brexit come what may’ was deeply unconservative. Nor of course is cutting tax inherently unconservative, but ‘borrow to cut tax’ undoubtedly was. Whatever got into so many Tory MPs during those careless Johnson years (‘Fuck business’), followed by the Truss interlude – that short flare-up of an -ism that should, like all ideological zealotry, be anathema to a true Tory?

And the irony is this. The principal opposition today, heading perhaps for government more by default than acclamation, has instincts too. Labour instincts. Socialist instincts. Instincts it knows (for Keir Starmer is no fool) it must suppress, deny, postpone, play down: because the voters are wary of them. Labour does not have a philosophy for government; it has an internal dialectic between those who want to follow their deep belief in collective action to improve mankind, and those who want to resist it for fear of losing elections. This is a terrible moral foundation for the challenge of government. Voters, even Labour loyalists, know that a Labour government in power in difficult economic times can only plead hardship – ‘the cupboard is bare’ – but has no anchored belief in the stringencies and market economics over which it will have to preside, forever crying ‘we don’t like it either, but needs must’. Only Tony Blair could persuade us that he personally wanted to move Labour on to the centre ground. Starmer can’t.

What better time, then, for a Conservative leadership that doesn’t just think balancing the books, getting debt down, treating tax giveaways with suspicion and keeping a tight rein on state spending are things forced upon us by difficult economic times – but believes they are good in themselves?

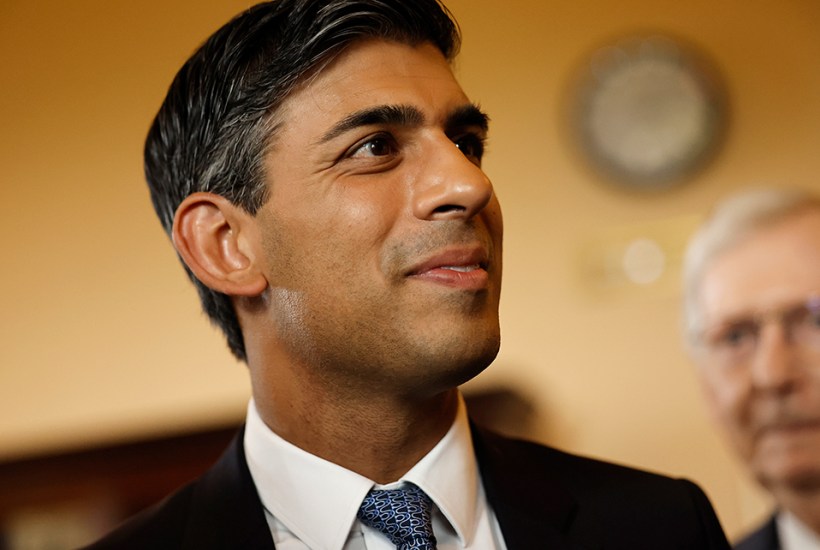

Rishi Sunak seems to be such a leader. Perhaps – though I’m not confident – his parliamentary party will now fall in solidly behind him.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in