I was walking last week from Canary Wharf tube station to my flat in east London – not far, little more than a mile, and the walk follows the Thames on the north side, away from traffic: lovely. But as I headed for the river, I saw trouble. A thick curtain of rain had descended over Blackheath across the Thames, and the wind was blowing strongly from that direction. The storm had not yet reached Greenwich, still clear, but the curtain was moving. After Greenwich the rainstorm would cross the river – and hit me. Umbrella-less, I quickened my pace.

Few others seemed to have noticed. People were ambling around, some sitting at outside tables at restaurants, some chatting on park benches. Others in smart business clothes were leaving their offices and heading off outdoors without a care. Soon they’d have to scarper, or get very wet.

I got very wet. Forewarning is no umbrella, but I’m glad I saw it coming. It gave me, if not control, the feeling at least of intelligent participation in my fate. When trouble is coming, I’d always prefer to know.

As it happens, this was also a week in which, for all with eyes to see, the lights on the national dashboard were flashing the clearest of warnings of a coming storm. Inflation reached 7 per cent and is rising. The big hike in National Insurance contributions to pay for health and social care was on the verge of hitting its unavoidably millions of victims. Many more were about to discover they had moved into a higher tax bracket because thresholds have not been raised. Energy price caps are being lifted; and for the rest of this year (and for how much longer nobody knows) almost everything is going to get more expensive while taxes are being raised and incomes squeezed.

You yawn? Yes, all this is public knowledge and often repeated. The storm is coming and we shall get wet. At some conscious or unconscious level, millions do already sense this. We are not fools, and dislike being taken for fools.

So why don’t those who lead us level with us? Why don’t they credit us with the maturity to understand the relative impotence of government to avoid the trouble ahead? Why do the Prime Minister at the despatch box and the Chancellor on the Today programme chatter endlessly about how this administration can help and is helping, rather than about how it can’t help much and shouldn’t pretend otherwise? We know we’ll be hit; we know how little a national government can do to shield its citizens from international turbulence; and it simply irritates us to hear politicians mutter something briefly about the limits of their power then desperately try to refocus attention on to the flimsy little measures they can take to soften the blow.

Perhaps, taking their mothers’ advice, they think you just have to keep accentuating the positive. In politics this is not always so. When people know the truth, false reassurance infuriates. Brandishing sticking plasters does not reassure when the wound is expected to be deep. So if something bad is coming, don’t duck, don’t distract, don’t exaggerate your powers to shelter. It may protect you best to lower people’s expectations, acknowledge their justified worries, warn them, and make it very clear you’re a realist, not a Pollyanna.

George Osborne did this to great effect after the 2008 banking crisis. In a dark suit at his 2009 party conference, he turned ‘austerity’ into something to be embraced. Whether or not his consequent policies were right, he sold them well: he prepared us for them with all the gravity of a hospital consultant with tough news to impart.

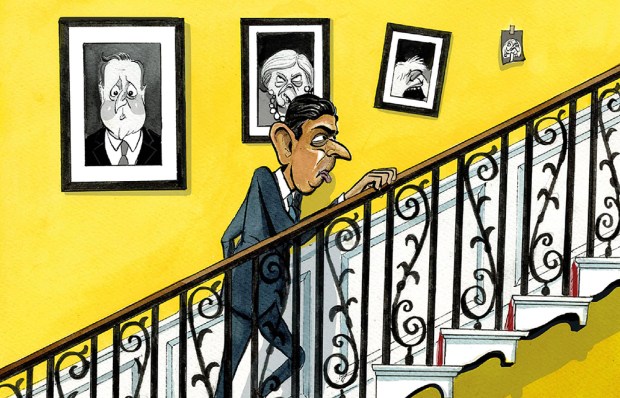

Rishi Sunak now needs to do the same. Recently our Chancellor made a speech that (engulfed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine) was hardly noticed, and that’s a pity. Do read it. Mr Sunak’s Mais Lecture at the Bayes Business School on 24 February tackles head-on the whispers that this is a politician who sees the trees but not the wood. It’s the most honest and uncompromising tour d’horizon of economic and political philosophy I’ve read in years. It’s decent and deep. Unashamedly conservative, and Conservative in the sense that I used to understand that term, Sunak lays fiercely into the idea that tax-cutting or borrowing will automatically pay for itself by stimulating growth. Quoting Adam Smith, he argues unapologetically for self-interest as a driver of prosperity, but – quoting Adam Smith again – he gives a central billing to simple benevolence: ‘However selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature which interest him in the fortune of others and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.’

The lecture sets out three goals for economic policy: ‘Capital. People. Ideas.’ Sunak explains how the tax policy he favours will encourage each of these three. With its unmistakably Californian tinge, the Chancellor paints quite a clear picture of a British economic future, and government’s place in it: enabling, prodding, stimulating. There is a vision here.

And vision is to be applauded. But Sunak is also a politician, and though his lecture lifts eyes to a sunny hillside opposite, he knows that first a storm is coming and it will be fierce and prolonged. For the voters the horrors will be financial, but for the Chancellor they will be political. He will have oversight over a storm which he has very little power to shelter us from. I cannot overstate how important it is to tell people this before it happens.

He has told us where he’s aiming for. Now he must tell us what we’re going to have to go through before we get there. Let the Prime Minister be the one to declare that all’s fine and dandy, and let the Chancellor be the one to declare that in the short term it is most regrettably not. And see who, in the end, the country prefers to trust.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in