When colour photography first came in at the start of the last century, it met a surprising amount of resistance from distinguished photographers. But Madame Yevonde loved it, owned it, revelled in it. She invested in a new Vivex repeating back camera, exhorting her fellows at the Royal Photographic Society in 1932: ‘Hurrah, we are in for exciting times. Red hair, uniforms, exquisite complexions and coloured fingernails come into their own… If we are going to have colour photographs, for heaven’s sake let’s have a riot of colour.’

But what she went on to create was far better than that. In her classical series ‘Goddesses’ (1935) she controlled colour like a Renaissance master, painting with it, creating atmosphere and character. Her immortal women are by turns vengeful, erotic, sad and gay; as emotionally radiant as a Powell and Pressburger composition, as camp as a Pierre et Gilles shoot. Her goddesses come to us familiar from their inheritors.

Never mind that the series – which boasts a duchess, a countess, a baroness, umpteen ladies and a Mitford sister – was sometimes problematic for critics, one of whom called it ‘a posh pit of decadence’ in the Guardian when it was last shown at the National Portrait Gallery in 1990. The ‘Goddesses’ are now the centrepiece of the headline show, Yevonde: Life and Colour,at the newly reopened NPG, which repositions her as a serious contender in 20th-century photography. They’ve even taken away her ‘Madame’. I rather liked its feminine pomp, though I suppose it does smack of fortune-teller.

‘She definitely used “Madame”,’ curator Clare Freestone told me, as she walked me round the show. ‘But on balance, things she had full control over were primarily “Yevonde”.’ She certainly never used “Cumbers”, her maiden name, although Freestone points out that her father’s commercial colour printing firm, Johnstone & Cumbers, where she toured large vats of ink as a girl, meant there was colour in her DNA.

The idea of the ‘Goddesses’ was sparked by an Olympian-themed fancy-dress ball in aid of the blind at Claridge’s in 1935. Opportunism, vital in a photographer, was one of her strengths and she caught her big fish with flattery, casting Diana Mitford as Venus – how could she say no? – and Margaret Sweeny, later the Duchess of Argyll, as Helen of Troy, while her friends and collaborators took the more challenging parts. Good old Dolly Campbell, wife of Yevonde’s cousin the speed freak Sir Malcolm Campbell, had her cheeks tracked with glycerine, as Niobe, weeping for her lost children, in homage to Man Ray’s ‘Tears’ of 1934. (This was rather Cassandra-like of Yevonde, as Dolly’s son Donald Campbell would indeed die dramatically in 1967 attempting to break a speedboat record.)

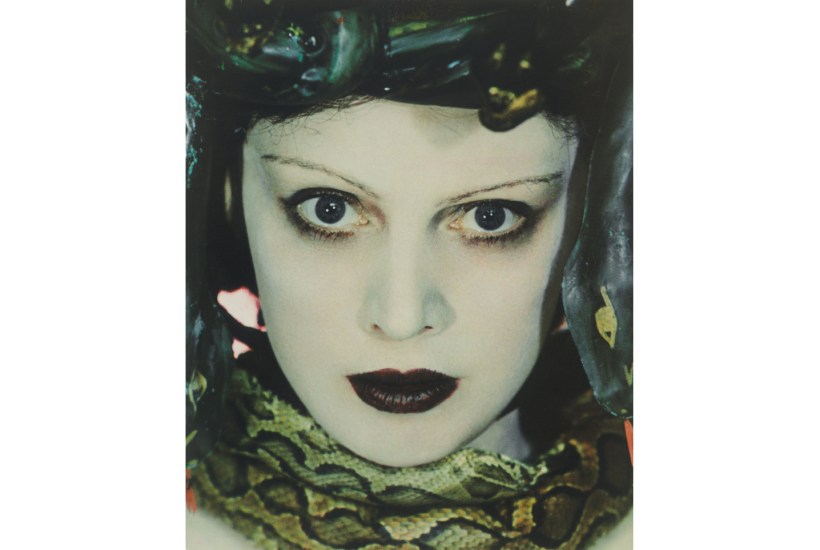

Mrs Edward Mayer (Madeleine Himmelstjerna), an Estonian émigrée with whom Yevonde and her husband Edgar Middleton played bridge at home in the Temple, was selected for Medusa. In the famous print, she stares existentially into the camera’s black abyss, wired toy snakes in her hair, python skin around her neck, lips painted a dull purple, skin sickly under green filters: exactly the ‘cold voluptuary and sadist’ that Yevonde wanted.

As Venus in pearls, Diana Mitford, then Mrs Bryan Guinness, wears a distant, soulful expression, with an air of unreachability that was fitting, perhaps, as she was just then falling out with everyone over her imminent marriage to the British fascist Oswald Mosley.

The atmosphere of the photograph of the future Duchess of Argyll is, frankly, ominous. The avoidant eyes, the vermilion lips, the grey and shadowy tones; the camera loves her and she seems to requite the feeling, but in 1963 that would be turned against her by her husband the Duke’s deposition of her private, sexually explicit photographs in court – although these days, of course, it’s apparently not acceptable to mention this, only to do a bit of handwringing, as the catalogue does, about the ‘status and treatment of women in society at the time’.

Far more cheerful is the portrait of Gertrude Lawrence, then a huge star, as a guitar-strumming Thalia, the muse of comedy. Negatives were expensive, so she used only two or three per sitting, but for Lawrence, she exposed eight.

Yevonde was always experimenting in her Berkeley Square studio with coloured cellophanes and deliberately under-exposed negatives. However her processors, Vivex in Willesden, sometimes sought to ‘correct’ these effects. Yevonde stressed in heavy handwriting that ‘nothing’ was to be changed, and the partnership settled. Studio assistants were sent on property-finding missions – a stuffed bull’s head from Camden Town for Europa to cuddle, etc. By nature droll, Yevonde used this as material for her autobiography In Camera; she wore her talent lightly, clever enough not to be too clever.

With puckish wit Yevonde placed a rogue goddess among the distinguished faces: a close-up of a bluebottle, resting on some lilies. This, apparently, is Metis, Zeus’s scorned first wife.

Metamorphosis was second nature to these women, as they exchanged maiden names for married names, titles, pseudonyms and yet new names on remarriage. Like true Olympians, the goddesses had a devastatingly high divorce rate, and keeping track of who is who is a perilous course. Sheila Chisholm, the sensuous Penthesilea, shot through with arrows and enjoying it terribly, was by marriage twice a lady and once a princess. Lady Alexandra Haig, daughter of Field Marshal Douglas Haig, became Alexandra Howard-Johnston on her first marriage, and subsequently, as Hugh Trevor-Roper’s wife, Lady Dacre. ‘Circe’ is so much simpler.

For this NPG retrospective, hitherto unseen negatives have been beautifully hand-printed by artist Katayoun Dowlatshahi (a process involving three colour plates laid on top of one another, and a lot of gelatine washed off by amber light). Et voilà: a long-lost goddess joins the others – Dorothy Gisborne as Psyche, wearing toybox wings and looking rather glum; her husband, like Yevonde’s, had recently failed to get elected as a Liberal MP.

The presiding goddess here is obviously Hecate, an older lady wreathed in soft grey net, thought for years to be Dorothy, the Duchess of Wellington, wife of the 7th Duke, and a poet whom Yeats adored; she has now been identified as Maud, Duchess of Wellington, wife of the 5th Duke. The striking triple portrait of her, once lost, has been found for this show, and it is a significant addition. In her younger years, Maud had sat for Sargent and De Laszlo, and in photographing her Yevonde in a sense received the baton from these painters, taking the evolution of portraiture forward into the 20th century.

When she exhibited a few of the goddesses as works in progress at her studio in Berkeley Square in 1935, they were hailed in the Times as ‘among the best direct colour photographs we have ever seen’. Yevonde went on to make important works in colour, such as George Bernard Shaw with roses and cream in his cheeks, up close, his writers’ hands soft and unlined (1937). She got a lot of stick, in that conventional era, for the daring blue light outlining his left cheekbone. But Yevonde insisted, in a lecture to the Professional Photographers’ Association Congress in 1935, that her motto was: ‘Be original or die!’

However, 1939 was an annus horribilis in which everything changed. Her husband Edgar Middleton died of cancer, aged 44. The Vivex colour-processing plant closed due to the war, and was never revived, and Yevonde was bombed out of her flat in Dolphin Square.

After the war, her work returned to black-and-white, with her drive to innovate finding its expression in monochrome solarisation. She continued to pull off brilliant coups, such as going to Ethiopia, aged 72, to photograph Emperor Haile Selassie, and revealing a sweet side to him in the portrait by getting his pet chihuahua to peep out from the cushions on his throne (in her memoirs she recounts that she mewed like a cat). She arranged for her archive to go to Roy Strong at the NPG in the early 1970s, and after her death in 1975 her work found enduring cult popularity. The artist Paula Rego called her style ‘homely surrealism, but sincere – I love it’. Photographer Mario Testino collects her work, and devotees include John Galliano and Tilda Swinton. But nothing in her long and distinguished oeuvre, not even a nymph-like Judi Dench from 1961, looks as modern as her work from the 1930s, when she created such a powerful evocation of a world that was about to vanish: a true twilight of the goddesses.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in