Normally, when you look at portraits you feel obliged to focus on the sitter. But quite often you’re thinking, ‘Ooh, what a lovely frock.’ Or, ‘Fabulous breeches!’ Here it’s the costumes that take centre stage. The point that this exhibition makes is that costume spoke volumes about society, particularly in the long 18th century, over the course of the reigns (and regency) of the four Georges. Compare the flounces and silk of a portrait of Queen Caroline in 1771 with the simple classical white muslin cotton of Princess Sophia in 1796 and you find nothing less than a revolution. The change resembles what happened in dress after the Great War: bye-bye Edwardian hourglass, hello flapper. Here cotton, a fabric inexorably associated with slavery, tells a larger story.

Something similar happened with men’s dress: when you see the portrait of Lord Byron in actual trousers (previously a sailors’ or boys’ thing) in 1807, you feel a transformation under way. Indeed one of the themes of the exhibition is how the upper classes slowly appropriated the style of the lower orders – if less dramatically than Marie Antoinette in shepherdess mode.

The show starts with a glorious picture of the goings-on at St James’s Park in about 1745. Royalty is to the fore with Frederick, Prince of Wales, in elegant Garter decoration. But look hard, and you see a man peeing against a tree, a milkmaid handing a cup to a nursing mother, a lady chasing a man across the green, a woman cowherd, a group of elegant young ladies – one black – soldiers with fabulous tall hats, a couple of clergymen and a woman in fashionable dress tying up her stocking, a red ribbon clenched firmly in her mouth. Oh, and on a bench, there’s a woman sitting down, with her hoop stuck up absurdly to the side.

And then it occurs to you: hoops really weren’t made for sitting down, were they? They gave you valuable personal space – who could get near you once you were inside one? – but were clearly a bugger in practice.

Most of the exhibition is given to portraits but the costumes and artefacts are fascinating too. People were smaller then: dainty and dignified. I felt like a heffalump as I contemplated the most exquisite piece (from the V&A), a heavenly sacque dress made from Chinese silk for Eva Maria Veigel, a petite woman, as wide as it was long, with embroidered fabric and a richly decorated train. It would be impossible to wear it without carrying yourself differently.

Nearby, there’s an equally dainty pair of man’s breeches, showing exquisite workmanship: a finely executed darn in the leg and a ribbon at the back for letting the waist out. Another theme here is that dress was designed to be adaptable; the material was so expensive, it had to be repurposed as fashions and figures changed. Reuse, recycle? The Georgians, like their predecessors, didn’t need telling.

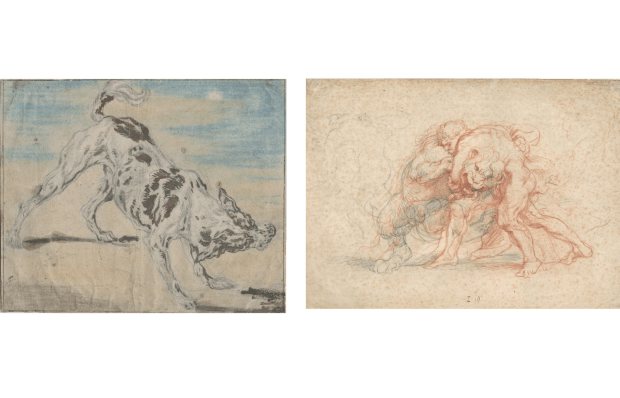

The most captivating piece was the stays, a wonderfully worked underpinning which, like a corset, held a woman’s figure in and pushed up the bust. It was made of finely stitched whale cartilage, less unforgiving than the steel-clad corsets of the Victorians. Loosening or discarding your stays, as in Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress, was an obvious sign of moral dissolution. They were made by men. While women were spinners and mantua makers, men were tailors and there’s a beautiful sketch by Louis-Philippe Boitard of 11 tailors sitting cross-legged on a bench next to a window (that work needed light) while a gentleman is measured at the front of the shop for a frock coat.

There are amusing caricatures: one by Rowlandson, of a man getting hoisted into close-fitting buckskin breeches, reminds you of nothing so much as a girl being squashed into tight-fitting jeans. And uniforms were plainly as much for strutting around as for the battlefield; George IV was captivated by his uniform for the Royal Hussars, ornamented with ‘silver Russian braid and 5 rows of best Plated buttons’. And rightly so. Indeed the question that this fascinating exhibition begs is: just when was it that men stopped being peacocks and began dressing boringly, and why? But that’s for another show.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in