It’s not until you see this exhibition of drawings by Henry Fuseli that you realise that most artists have really not done anything like justice to women’s hair. Fuseli was obsessed with it, particularly that of his wife Sophia, a former artists’ model 20-plus years his junior. Hers was wildly extravagant even by the standards of the time – late 18th, early 19th century.

For most art buffs, Fuseli, one of the most idiosyncratic artists of his age, is best known for ‘The Nightmare’, his lurid Gothic painting of a curvaceous sleeping woman with a demon squatting on her belly, shown in the Royal Academy exhibition of 1782; the drawings in this Courtauld exhibition show another side.

All his women have mesmerising coiffures, from two respectable sisters in his native Zurich, to a young Spanish woman. Here the sketch is usefully juxtaposed with an illustrative picture of a Roman matron from the 1st century AD with similar elaborate curls; in an age where classicism was all the rage, one way for women to imitate antiquity was by replicating the elaborate hairstyles of imperial Rome.

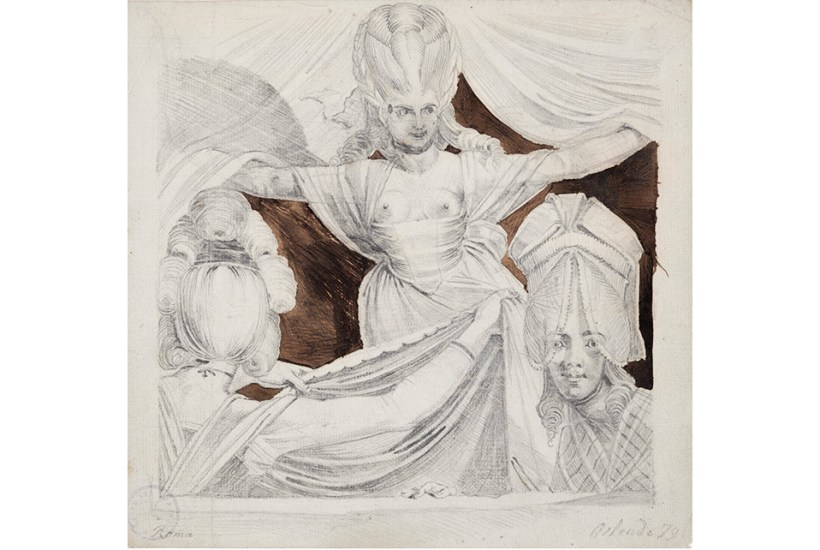

The hair Fuseli depicts in this eye-opening exhibition is tortured into the most extraordinary displays, coiffed into elaborate swirls, teased into phallic shapes, dotted with gems that practically stand out from the page. Often the hair takes precedence over every other aspect of the subject, which accounts for the number seen from behind. One lady has her back to us at a dressing table, where her remarkable plaits seem to be suspended from a kind of pulley. Another has her hair teased into an unmistakable phallus. The subtitle to this show is ‘Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism’, and there is undeniably something weird going on here. Fuseli in his youth considered the Protestant ministry, and it’s hard to escape the view, embraced by the curators, that woman here is seen as temptress. And sometimes worse: one smiling woman with a hairpin between her teeth, entitled the child killer (in Greek), suggests…what? An abortionist?

As often as not, the more elaborate the coiffure, the starker the undress of the lady in question. In the drawing entitled ‘Kallipyga’, the dress of a lady looking in a mirror has been hitched up to expose her bare bottom. One of the most elaborate head-dresses, with a little ruff at the neck, is worn by a bare-breasted courtesan; several of his prostitutes are elegantly dressed and coiffed, all the better to show their naked, improbably moulded breasts.

Much of this is high-class pornography – and the way an earnest bespectacled young American girl was pointing out to her companion the detail of the filthiest drawing of three nymphs pleasuring a recumbent male (his face invisible) suggests that it retains its titillating effect. But it would be doing Fuseli an injustice to see his work merely as erotic. He regarded himself as the finest draughtsman in the country; some of these drawings resemble Blake, others Rowlandson, all are assured and many have the dramatic light and shade he practised even as a child. Perhaps the best way of putting Fuseli is to say that Aubrey Beardsley would have loved him… or, if he did know him, it showed.

Helen Saunders (1885-1963), also at the Courtauld, could not be more different: she’s billed here as a ‘Modernist Rebel’, but she wasn’t a rebel of a showy kind. She embraced abstraction before the Great War, and returned to figurative painting after it. But it’s hard to pin her down; the artists she admired were Cézanne (there are a couple of lovely studies of his house here), Gauguin and Van Gogh – loners rather than disciples of a school. She disliked being labelled.

She did sign Wyndham Lewis’s vorticist manifesto (one of only three women signatories), declaring that art must embody the bareness and hardness of industrialisation, and was close to him for a time. She could be, and was, billed as a cubist, given her simple flattened planes. There’s a fine pencil portrait here of her friend, Blanche Caudwell, where the unmistakable outlines of the cheekbones and temple are rendered as geometric shapes.

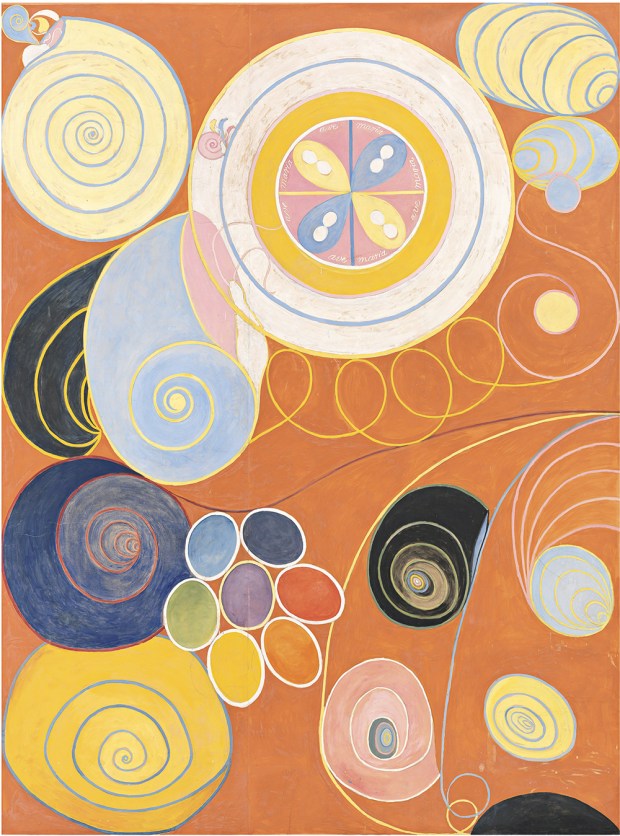

Her vorticist abstract works have real power: one in black and white shows jagged lines curving menacingly in on themselves; another seems to show imploring line figures imprisoned within triangular darkness. But she’s a colourist too, as in the screaming lines of ‘Black and Khaki’, where a stick man seems to shoot out of a rifle – painted in 1915.

Is there a feminine side to her work? ‘The Mother and Child with Elephant’, showing a mother breastfeeding a recumbent child, is intensely natural, notwithstanding the oddly angled nipple. Her female figure on a hammock, c.1913-14, is contorted, agonised and very Picasso.

This little exhibition is a small sample of her work, much of which has been lost, but there’s enough to make you want more – much more.

The post Mesmerising and eye-opening: Courtauld Gallery’s Fuseli and the Modern Woman reviewed appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in