Live Nation Entertainment globally brings to life more than 40,000 shows, 100 or so festivals, and sells more than 500 million tickets a year. In 2016, the US-based company bought controlling stakes in Australia’s largest music festivals, Splendour in the Grass and Falls Festival.

Live Nation is one of a trio of US companies that in recent years has swooped on many of the companies that form Australia’s live-music industry. The threesome, which includes AEG and TEG, is estimated to control 85 per cent of an industry that comprises agencies, festivals, ticketing, and venues.

A small number of companies dominating an industry is a common structure in Australia. The ‘Big Four’ dominate banking. Just two companies hog supermarket sales. A pair corner hardware. Another duo controls the domestic airways. Telecommunication services, oil refining, payments, steelmaking, and utilities including electricity are other industries where market power channels to a few.

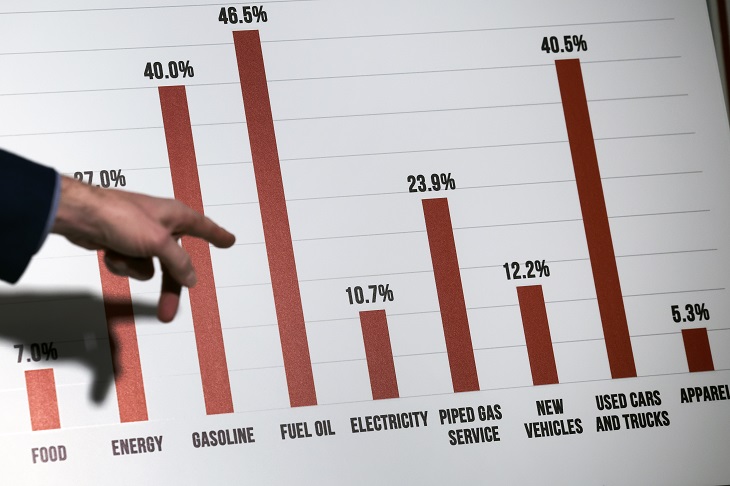

Concentrated industry structures are textbook examples of where a lack of competition leads to excessive profits at the expense of consumers. When input costs rise, these businesses can preserve their profit margins. As price makers, they can pass on these higher costs to their ‘price-taking’ customers.

Given the newfound concentration in entertainment, it’s probably no coincidence that when Australian inflation reached a 32-year high of 7.8 per cent in 2022, ‘recreation and culture’ (+9.0 per cent) was the third-most inflationary of the 11 subgroups that form the consumer-price index. (Housing and food and non-alcoholic drinks were the top two.) Studies show ‘markups’ – the gap between production costs and selling prices – have risen in recent decades as competition fell across advanced economies.

One economic consequence of market concentration? It makes it harder for central banks to reduce inflation to their targets, typically 2 per cent (2 per cent to 3 per cent for the RBA).

If only such inflation-prone industry structures were the sole challenge for central banks in their quest to quell inflation. Six other challenges (in no particular order) are making it harder for tighter monetary policy to rein in price increases.

A second challenge is that supply disruptions are fanning price increases. These supply woes include the Ukraine war, sanctions against Russia, the pandemic closing factories, global political rivalries (China versus the US) that are reversing globalisation, bad weather hampering farm production, even ransomware attacks. Included too is a shortage of rental housing that is boosting rents. The problem for central banks is that tighter monetary policy, which seeks to arrest inflation by curbing demand, can’t solve supply hiccups.

A third factor acting against slower inflation is that economies are running at full employment. This helps workers secure the higher wages that could spark the wages-price spiral that central banks dread. In Australia, unions, backed by Labor governments that have removed caps from public-service wage rises, are intent on spurring wage increases.

A fourth issue – a longer-term one stoking wages inflation in advanced countries – is that low birth rates and the consequential decline in working-age populations bolster the bargaining power of many workers.

A fifth reason why inflation will be hard to stomp out is that government fiscal settings are stimulatory, and thus are at cross-purposes to tighter monetary policy. Washington is running a budget deficit at 5.3 per cent of GDP. The eurozone fiscal shortfall is 3.3 per cent of output. Canberra, perhaps surprisingly, could record a budget surplus this fiscal year thanks to bracket creep, higher commodity prices, and a growing economy at full employment boosting profits and lowering welfare payments. But a surplus built on favourable terms of trade is not the brake on inflation that would be a surplus engineered by trimming spending and raising taxes.

The sixth problem is ‘greenflation’. The move from fossil fuels to renewables is inflationary because the supply of fossil fuels is falling before demand has dropped. The shift, for instance, is expected to boost electricity prices in Australian eastern states by more than 20 per cent from July 1, perhaps even 30 per cent in Victoria.

The last reason given here for why inflation is likely to persist is that central banks are yet to boost interest rates to levels whereby real interest rates are positive. Key benchmark rates are below inflation readings in major economies – in fact, many say the world is witnessing the longest stretch of negative interest rates in modern times. While record debt make economies more sensitive to each rate increase, it’s a stretch to see how negative real rates can reduce inflation to the 2 per cent to 3 per cent that central banks seek.

The dilemma for central bankers is thus. Their rate increases so far are hitting their economies but not so much inflation. Only positive real interest rates at heights that would trigger recessions can conquer inflation. Count on more rate increases until economic contractions are underway.

To be sure, higher interest rates are slowing inflation in major economies. Australia’s inflation, for instance, slowed to 6.8 per cent in the year to February and could cool more. But not by enough to stop more rate rises. Companies aren’t doing anything wrong when they pass on price increases – ignore the bleats about ‘greedflation’; these are the businesses with Warren Buffett ‘moats’ that investors prize. No signs of a wages-price spiral have emerged. Australian real wages, in fact, plunged by the most on record in 2022 (even if wages growth of 3.3 per cent over the 12 months was the fastest pace in 10 years). But that 4.5 per cent drop in real living standards is what spurs industrial action. Some supply-side shocks might ease. But only this month Opec unexpectedly cut oil production and many expect Brent Crude to jump from US$75 a barrel in March to above US$100. So more inflationary pressures.

The best indicator that central banks might need to lift interest rates to hurt their economies to tame inflation? Central banks in the eurozone, Switzerland, UK, and the US this month raised rates even after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank cast doubt on the stability of the global financial system.

A possible pointer to when central banks might be done? Perhaps when mortgage owners are so broken they can’t afford to attend concerts.