Thanks to the work of the caricaturists of the late 18th century, the mistresses of the future George IV – Mrs Fitzherbert, Mary ‘Perdita’ Robinson and Lady Jersey among them – are better known to us than his eventual wife, Caroline of Brunswick. The Prince of Wales’s decadent, spendthrift lifestyle (we see him emerging in 1788 from a lavish four-poster from which Mrs Fitzherbert arises en déshabillé), combined with his florid face and corpulent physique, were perfect fodder for this new genre of artistry, which used caricature (or visual exaggeration) to make political points. James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and Isaac Cruikshank were its chief proponents. Their high point was the 1790s, when their ingenuity was fuelled by the cost of the wars with France and the vulnerability of the monarchy created by George III’s illness and the perceived unsuitability of his son to take over as regent.

Alice Loxton’s UPROAR! celebrates these early satirists and printmakers in a book that seeks to evoke the explosive, gossipy atmosphere of that period, when print culture became affordable and the potential of mass communication was first understood. In his ‘A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion’ (1792), Gillray created a memorable image of the prince’s sulky, infantile arrogance and over-stuffed greed from which the royal family has never quite managed to escape. (Prince Harry’s discomfort with the media has deep roots.)

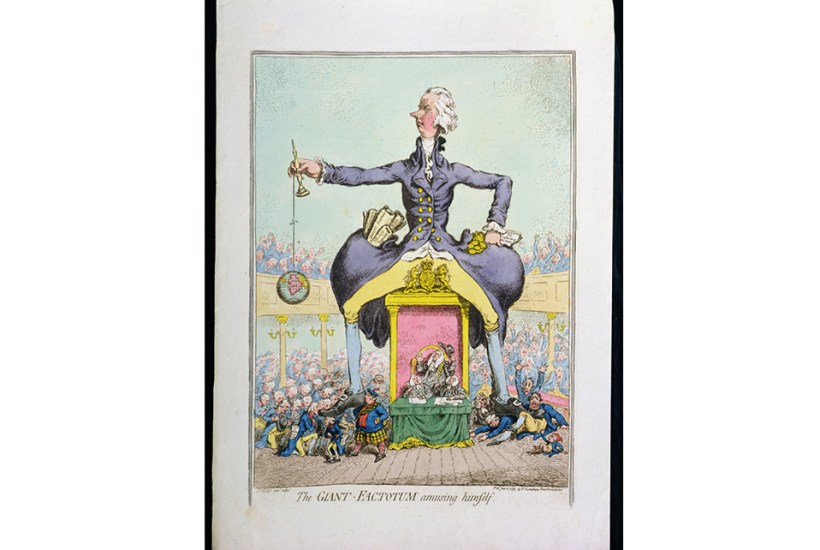

Gillray was equally robust in his attacks on William Pitt, the prime minister. ‘The Giant Factotum amusing himself’ of 1797 depicts Pitt as a monstrously tall figure astride the chair of the Speaker of the House of Commons and the royal coat of arms, crushing the opposition members of parliament, with his pockets bulging with guineas and lists of the ‘volunteers’ deployed in the war against France. There is, as with all successful satire, an ambiguity about this print. At the time, Gillray was secretly receiving a government pension.

Not that there is much opportunity for nuance in Loxton’sfast-flowing, highly seasoned narrative. The author, who has a formidable following on TikTok and plays a starring role on the YouTube channel History Hit TV, has a readable, engaging style, but her love of cliché often obscures her meaning. ‘Stood at the crossroads of life’, ‘an elephant in the room’ and ‘cut the mustard’ are deployed on a single page. ‘Teenage angst’, ‘trailblazer’, ‘tears up the rule book’ and ‘watershed moment’ describe Gillray’s transformation from the son of a strict Moravian family who delights in sketching British birds to the bibulous graphic artist we know, producing prints as gruesome as ‘Un petit souper à la Parisienne’ from 1792. The artist Joshua Reynolds is described as ‘a 49-year-old ear-trumpet-wielding vicar’s son from Devon’; all of which is true, but tells you nothing about why we should know about him.

The careers of Gillray (to whom Loxton dedicates her book), Rowlandson and Cruikshank were pivotal, making the most of the possibilities opened up by developments in the printing process. They understood how the speed of production and the power of the engraving burin could be used to comment on what was happening in the world of politics, much like the satirists Swift, Dryden, Addison and Steele had done with the printed word earlier in the century. Their influence lingers on in the work of today’s cartoonists, Michael Heath, Martin Rowson and Steve Bell among them.

The market for their prints was dominated by just three printshop owners, William Holland, Samuel Fores and Hannah Humphrey, who acted as agents. Humphrey in particular is an influential figure about whom we should know more. Gillray lodged with her for much of his career, and she continued to care for him after his descent into dementia. Her brother William was also a print-seller, but it was Hannah who secured the rights to publish Gillray’s works, and she succeeded in passing on her business as a going concern after her death in 1818. What part did she play? Did she suggest topics for illustration?

How and why are words that don’t often enter Loxton’s frame of reference. She fails to place the trade in prints at this time in the context of the publishing revolution. Who was buying them? Where were they displayed after purchase? We do hear about Hogarth (born 50 years earlier), but not enough about the influence of his satirical ‘Gin Lane’ or ‘The March to Finchley’. Loxton includes an illustration by Edward Francis Burney (not Burley as he is named in the caption) but does not discuss his work. And although she takes herself off on an etching course to understand how Gillray produced his prints, her explanation does not highlight the extreme skill required to etch in reverse.

In a footnote, tongue-in-cheek, Loxton (inspired by Thomas Paine’s success with his The Rights of Man in 1791) hopes for sales of 1.5 million. That would give Gillray, Rowlandson and Cruikshank the attention they most truly deserve. Yet such a breezy race through their achievements does little justice to their stiletto-like precision and desire to nail a point.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in