The Belgian film Close, written and directed by Lukas Dhont, which won the Grand Prix at Cannes and is up for an Oscar, is a coming-of-age-story that’s exquisite and heart-breaking. Take tissues, and probably not just the one box.

Dhont’s starting point was psychologist Niobe Way’s book Deep Secrets: Boys’ Friendships and the Crisis of Connection, which is based on hundreds of interviews and showed that boys have deeply intimate, confiding friendships until adolescence when they are socialised to withdraw from one another. (Just to be on the safe side I asked my adult son if this was his experience. ‘Yes’, he said.)

Here, our boys are Rémi (Gustav De Waele) and Léo (Eden Dambrine), who live in rural Belgium and are about to start secondary school but for now it’s the summer holidays. They run through fields of shoulder-height flowers (Léo’s family are flower farmers). They race their bikes, play make-believe action games and are inseparable. They stay at each other’s homes, spooning sleepily, limbs entwined, amid shafts of early-morning sunlight. (Sit on that, Terrence Malik.) I was deeply touched, for some reason, by their little white vests, purchased, no doubt, from the Belgian equivalent of M&S. They are blissfully unselfconscious and maybe it’s homoerotic, maybe it isn’t. Are they gay? Is one gay but not the other? Or is neither? We never really know. We only know that this innocence, this childhood idyll, this uncomplicated love they have for each other, cannot last. But what will happen to the boys? The waiting is torture.

They start at their new school. Initially they remain joined at the hip. ‘Are you a couple?’ asks a girl, not cruelly, but out of curiosity. Léo becomes uneasy. A boy mutters a homophobic slur. Léo’s unease multiplies. When they lie in the sunshine and Rémi puts his head on Léo’s lap, Léo wriggles away. A play wrestle between the two turns into a horrible fight. On paper, it sounds clumsy, unsophisticated, but on screen Léo’s withdrawal is subtle and told incrementally via a series of observational vignettes.

The metaphors keep coming. Brutal industrial machines crop the flowers for market. Léo joins the ice-hockey team and, at his first practice, the camera shifts skywards to a flock of birds taking off. I’m not sure we sufficiently appreciate the amount of metaphor work birds put in at the cinema, by the way. They’re always at it. In this instance, Léo, we are being told, is prepared to go with the flock and be reshaped by it. Rémi, baffled at first, now feels painfully rejected.

I can’t say what does happen, and it’s possibly not realistic, but trust me when I say this: it’s devastating. The second half of the film focuses on the aftermath and all that can’t be expressed and I’d best not be more specific than that.

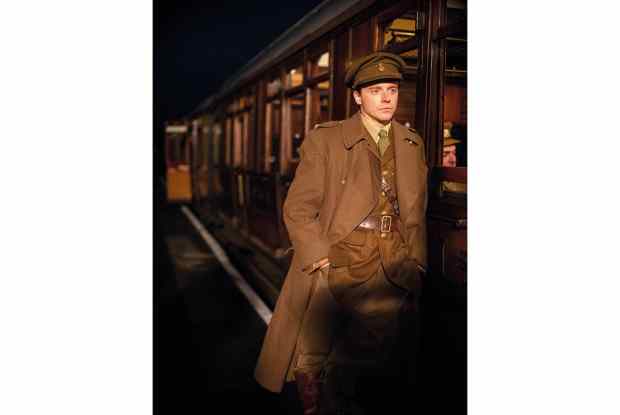

There are several gripping scenes, including one between Léo and his mother (Léa Drucker) on a school coach and one between Léo and Rémi’s mother (Émilie Dequenne) in a forest that’s also pierced by Malik-like sunlight. The performances are all wonderfully naturalistic. Dhont did not want child actors. He auditioned in schools and saw 580 boys before he cast De Waele and discovered Dambrine, a ballet student, when he spotted him on a train. They rehearsed for six months with cameras in the room before they even started filming. The result feels sensuously instinctive, rather than plot-driven, as if the story is simply telling itself. It put me in mind of Rob Reiner’s Stand by Me (1986) and the last line said by one of the characters: ‘I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was 12. Jesus, does anyone?’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in