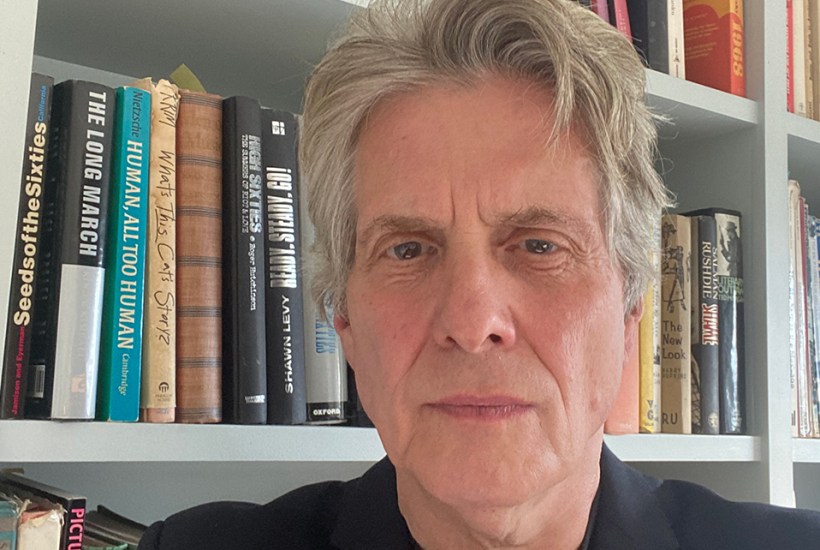

‘This is a book about how you don’t get over it,’ You Are Not Alone begins. If you’re new to bereavement, looking for a way through the death of a loved one, perhaps this doesn’t scream of optimism. But Cariad Lloyd’s warmth, generosity and gentle pragmatism makes her book one of the most reassuring I have read.

She is a member of ‘the club’ – the Dead Dad Club. Her father died 24 years ago of pancreatic cancer when she was 15. She is also the host of the award-winning podcast Griefcast, through which she has interviewed many bereaved individuals – comedians, writers, actors, chefs, artists – who have suffered the loss of children, parents, grandparents, siblings, friends and pets. You Are Not Alone is the distilled wisdom of her experiences and those of her guests. But this isn’t a self-help book – Lloyd isn’t a grief counsellor or a palliative doctor; she is a comedian who happened to lose her father at an early age – and it isn’t a memoir either. Itis an account of carrying grief and living alongside it, imperfectly.

The book is made up of personal narrative, digested grief theory and practical advice, while drawing on the experiences of those she has spoken to on Griefcast. The combination provides an insight into the nuts and bolts of grieving, the rights and wrongs. (There are no ‘wrongs’, Lloyd is at pains to point out, but it doesn’t always feel that way at the time.)

It is divided into practical chapters that explore the realities of how grief feels and mutates, what we can do to help ourselves and others and how we confront our own mortality. Interspersed are vignettes from Lloyd’s own journey. She is an old hand when it comes to grief, variously describing herself as a grief ‘elder’, ‘Captain Grief’, ‘Queen Grief’ and someone who, when it comes to mourning, ‘got there early and set out the nibbles’. She chronicles shock and anger, repression, aborted attempts at therapy and consequent self-recrimination. For many who have been bereaved, this will be an uncomfortably familiar story.

And that’s rather the point. As Lloyd observes: ‘What’s happened to us isn’t unusual. It’s normal to know death. Grief is normal.’ She goes on to describe her more successful therapy, the help she found in listening to others tell their stories and how her life has grown around her grief. It’s a remarkably enjoyable read considering the subject matter – and of course it helps that she’s funny.

But not all griefs are equal. Along the way Lloyd examines the different types of death she has been exposed to through the podcast. One example is that of Jayson Greene, whose two-year-old daughter was killed by falling masonry while sitting on a park bench with her grandmother. Lloyd dreads the prospect of speaking to him and wants to avoid the conversation. ‘It terrified me, the grief,’ she admits – ‘as if it was somehow dangerous to my children, as if it was catching. It was a reminder that the urge to run away from death is pretty universal.’

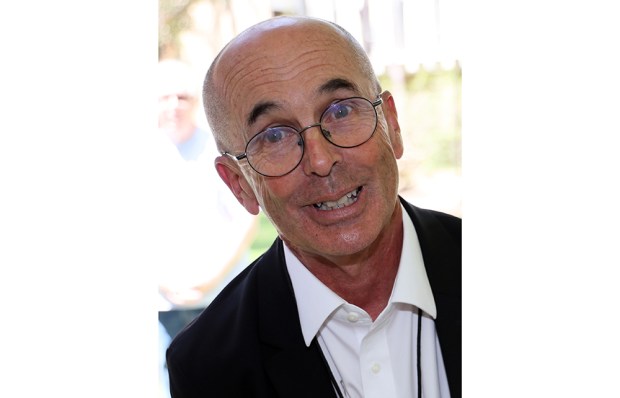

This is how I felt when reading Cosmo Landesman’s Jack and Me. I wanted to run away. Landesman’s son Jack died by suicide in 2015, aged 29, after a protracted battle with depression and drug addiction. His thoughts about suicide were so all-consuming that it became a regular topic of conversation: Jack ‘talked about it too much. Made jokes about it too much. And so did I. We did suicide banter together’, Landesman writes.

He began the book in 2015 as an antidote to neater, more upbeat grief memoirs he’d read that provided something approaching a happy ending. ‘This book is not one of those books – the kind that offers feel-good-grief, with their mawkish mix of misery and happy memories all wrapped up and resolved in a nice pink bow of comforting closure.’ But by the time he returns to writing it some years later his outlook has softened. He has overcome his aversion to saccharine life lessons. ‘Whether we fail or succeed in helping those with suicidal thoughts, at the end of the day we have to try and make a difference,’ he says, before embarking on this first of his self-proclaimed ‘banal’ life lessons.

Landesman is right that this is not feel-good-grief. Despite his change of outlook, he is a masochistic narrator, raking over every unkind word, every missed opportunity, every moment of exasperation, while examining his repeated unsuccessful attempts to pull his son out of his situation. He is almost unbearably honest, worried that the frustration he felt with Jack meant that by the time he died he no longer loved him.

The book is an investigation into parental love, its limits and its responsibilities. What it shows in high definition is the frustration of living with and loving someone who has debilitating depression. His portrait of Jack is unflinching, and their rows are re-examined often in the form of remembered or imagined dialogue or in their emails to one another. Landesman is torn between justifying the difficulties of their relationship and wishing for a do-over. It is profoundly sad.

I finished it feeling exhausted and confused. The suicide of a child is every parent’s worst nightmare. Like Landesman, I was, perhaps unconsciously, looking for what he did wrong with Jack. I found myself scouring his story for a what-not-to-do in parenting. I know this is profoundly unfair, but I wanted him to have made mistakes, to pinpoint an iron-clad reason why his son did what he did, a list that I could absorb and avoid. But of course that’s not how suicide works, and why it’s so frightening. ‘When you dig into the mystery of why, you rarely discover a conclusive answer that brings you the peace you crave,’ he realises.

In one way, Lloyd and Landesman’s books are diametrically opposed. You Are Not Alone is explicitly designed to reassure, to show the reader that while they won’t ‘get over’ their bereavement they will learn to live with it and feel happiness again. Jack and Me is deliberately provocative. It challenges the reader (and, arguably, the author) to find something positive in the mess of this very particular grief. But both books invite compassion for the dead and those they leave behind.<//>

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in