‘Graphic’ scenes of violence are now associated with film, but the word betrays an older ancestry. The first mass media images to shock the public were engravings documenting contemporary social ills pioneered by the Victorian magazine The Graphic, though the association goes a long way further back, to Jacques Callot’s etching series ‘Miseries of War’ (1633) recording atrocities perpetrated by both sides during the French invasion of his native Lorraine in the Thirty Years’ War.

The grisliest of those images, ‘The Hangman’s Tree’, is the earliest work in Bearing Witness? Violence and Trauma on Paper, at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. The prints and drawings on display are not all about war – social deprivation is the subject of Käthe Kollwitz’s 1922 sheet of drawings of German children, racial oppression the target of South African printmaker Ndabenhle William Zulu’s 1992 linocut ‘Peace Now!’ – but the role of the artist as witness is most neatly encapsulated in the title of Goya’s etching, ‘I Saw This’ (c.1810-11), from The Disasters of War.

Artist witnesses are thin on the ground these days. Where are the John Keanes and Peter Howsons of the Ukrainian conflict? Or the Don McCullins? No iconic images have come out of recent conflicts, only newsreel of reporters in bulletproof vests. Perhaps a Ukrainian or Russian artist-soldier will emerge to record his memories, like Otto Dix in Der Krieg after the first world war. Sometimes these things take a while to surface. Goya’s Disasters of War were only published in 1863, 35 years after his death – a howl of protest from beyond the grave by an artist who spent much of his career serving the court responsible for said disasters.

Unlike Goya – or Manet in his matter-of-fact close-up on a barricade strewn with bodies in ‘Guerre Civile’ (1871-73) – Marcelle Hanselaar wasn’t a witness to the events portrayed in her 2015-17 suite of etchings The Crying Game, 20 of which, recently acquired by the Fitzwilliam, dominate one wall. The impetus for the series, quite different from her previous work, sprang from her feeling of impotence under bombardment with constant news reports of violence and trauma from around the world; the feeling that as an artist her only response was to ‘draw, and in so doing, draw attention’.

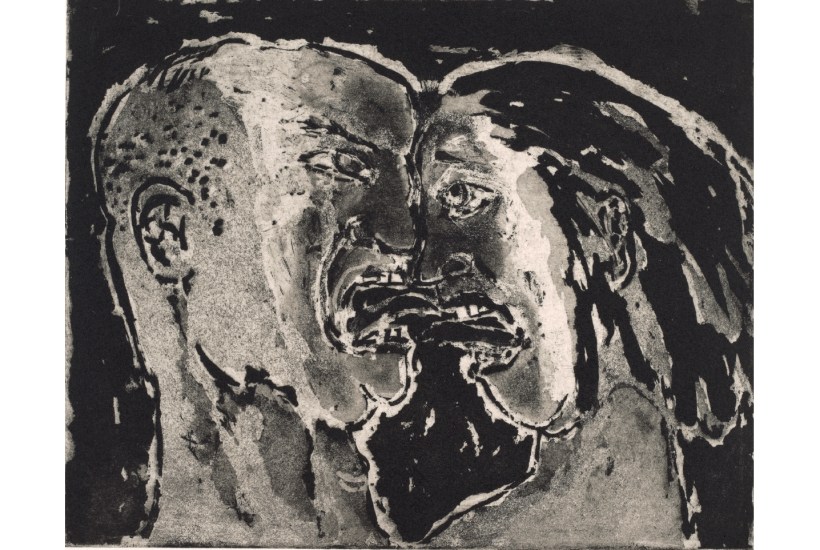

Among echoes of Dix and Goya – both inspirations – there are flashbacks to Hanselaar’s more familiar world, a petit guignol theatre of the absurd: the amputee in ‘She’ who collects limbs like firewood has lost his trousers and acquired Mickey Mouse ears, and the fleeing parent with the dying child in ‘Remnants of civilization II’ has a carnival mask perched on his head. The rage that consumes humanity in this world gone mad is not confined to the field of war; it invades a brutalist estate where a junkie shoots up and a teenage hoodie threatens another with a blade, and boils over into a shouting match between a ‘Warring couple’, their eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation reminiscent of the gurning heads of Dix’s ‘Dead men before a position at Tahure’.

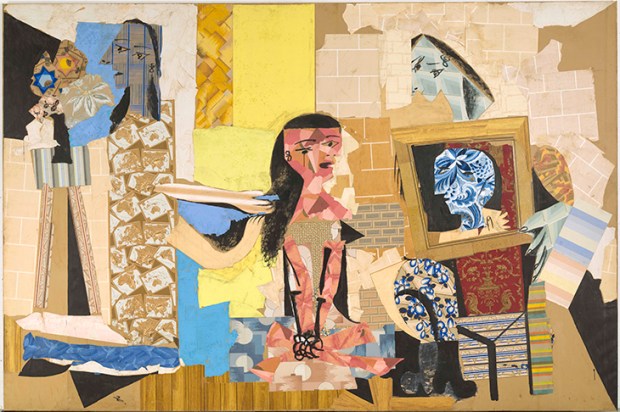

Dix is a notable omission from a show designed to put Hanselaar’s series in context; unfortunately the Fitzwilliam doesn’t own any prints from Der Krieg. Down the road at Kettle’s Yard, other works from its collection are on loan to a very different exhibition designed to inject a bit of Caribbean colour into an enclave of European modernism. In Paint Like the Swallow Sings Calypso, three British-Caribbean artists – Barbados-born Paul Dash, Jamaican-born Errol Lloyd and Trinidad-born John Lyons – have chosen images from both collections to hang alongside their own works on the theme of carnival. They kick off with some strangely decorous Italian Renaissance bacchanals – even the tipsy toddlers in Giulio Carpioni’s 16th-century ‘Bacchanal with Satyrs and Putti’ are behaving themselves (though the adult bacchante sleeping it off under a tree suggests that we may have missed the action) – and a courtly ‘Torch Dance at Augsburg’ by Dürer before the carnival spirit breaks out in earnest in Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s ‘Village Festival’ (1632), with concomitant vomiting, urinating, groping and fighting.

Caribbean carnival was born on the wrong side of the blanket as the mixed-race progeny of the masquerade ball and the Christian carnival – imported by colonisers from Europe – and bamboula dancing brought by slaves from Africa. Given its origins, it’s a more complex beast than conveyed by Errol Lloyd’s bright, cheerful paintings of ‘Notting Hill Carnival’ (1988). A darker undercurrent is felt in Paul Dash’s ‘Masked Stick-Lick Fighters Parade’ (2019), with its sinister Ku Klux Klannish hats, and in the shadowy figure of the horned Jab Molassie devil gyrating in John Lyons’s ‘Mama Look A Mas Passin’ (1990). ‘As an artist and poet,’ says Lyons, ‘I self-indulgently luxuriate in the idea that nothing is ever what it appears to be.’ Even in graphic images of war, there’s no black and white.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in