The dead went unburied and the rubbish piled high in Leicester Square. Then a suntanned Jim Callaghan arrived back at Heathrow from a summit in Guadeloupe to tell reporters, in words fairly paraphrased in the Sun headline: ‘Crisis. What crisis?’ The Prime Minister said that he didn’t think the rest of the world, looking at Britain, would see a country going down the tube. The folklore of the Winter of Discontent in 1978-79 is ingrained in the nation’s collective memory. It was the final act of a miserable decade of three-day working weeks and power cuts.

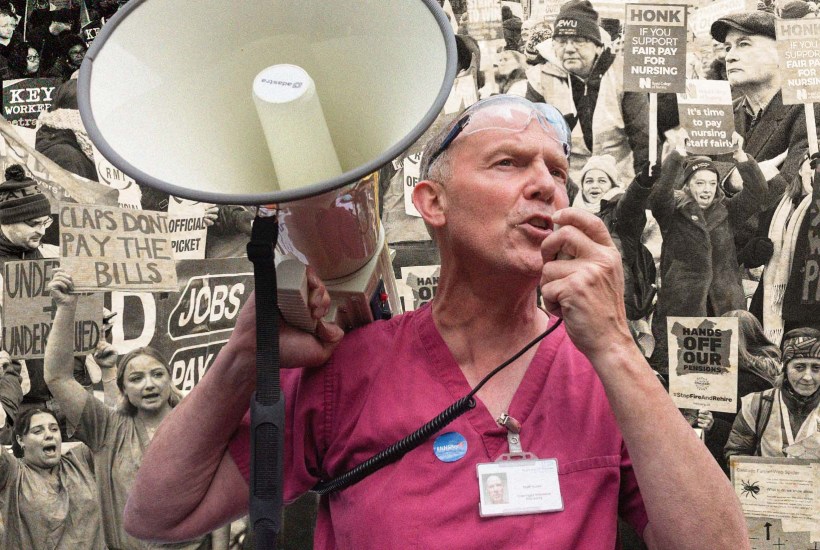

Some are suggesting that we are facing a second Winter of Discontent. Certainly, look at the strike calendar for January and there is something going on – or not going on – every day. This week was the turn of Abellio bus drivers in London, teachers in Scotland, nurses (again), ferry workers in Northern Ireland and environmental workers. Next week ambulance staff will take yet more days off. These strikes will presumably cause inconvenience for some. But does it really feel as if the unions are in control of the country’s destiny as it did 44 years ago?

In 1979, trade unionism in Britain was at its apogee. The number of union members had reached its peak at 13.2 million, higher than at any point before or since. The closed-shop rule of mandatory union membership in some industries meant that it really was a case of ‘one out, all out’.

The election of Margaret Thatcher in the wake of the Winter of Discontent reversed all that. Closed shops were made illegal; strike ballots became obligatory. Union membership plummeted as industry declined. The number of members fell to a low of 6.23 million in 2016, recovering only slightly to 6.44 million by 2019. From over half the workforce in 1979, union membership has slumped to 23 per cent, and even that is concentrated in a few industries.

While the image of trade unionism is still that of blue-collar workers gathered around the brazier, shouting ‘scab’ at their non-striking colleagues, the reality couldn’t be more different. Union membership is now highest in professional occupations, at 35 per cent. It is down to a quarter of workers for process, plant and machinery operators.

The railways (where 70 per cent are union members) and the NHS (where two-thirds of nurses are members of the Royal College of Nursing) are the exceptions. In most other occupations it would be difficult for a union to muster enough staff to close down a workplace. It is a case of ‘one out, a few more out, but as for the rest of us we’ll see you tomorrow as usual’.

In 1979, 29.5 million working days were lost to strikes – itself a small fraction of the 160 million days lost in the year of the general strike in 1926. The current winter will not compare. For all the union discontent, the question for most people going about their business in 2023 is: ‘Strikes? What strikes?’

True, it has been a horrible few months for rail passengers, but even there the unions have lost the power they wielded only a few years ago. Covid lockdowns have forced employers to devise ways of remote working which, while not always ideal, enable many businesses to carry on pretty well as normal. Moreover, working practices have never returned to what they were before the pandemic. Commuter traffic is earning just 59 per cent of the revenue it did in 2019, business travel a mere 40 per cent. Nearly a third of people work mostly from home.

It was a very different story four decades ago when rail unions had as much power to turn the lights off as the National Union of Mineworkers. In those days, most UK electricity was generated by British coal delivered to power stations by train. Rail workers have no power whatsoever to close down the gas plants and wind farms which generate most of the UK’s electricity now.

It is the same for postal workers. Although many Spectator readers have been messed around with the Christmas issue, which in some cases arrived in the new year, the unions are a long, long way from the power they wielded in the 1970s. The number of letters has collapsed since then as people switch to email and other electronic means. (The Spectator website was available throughout the period.) There are now far more companies delivering parcels and the whole industry has atomised into a miasma of communications services beyond the reach of the most militant unions.

In 1979, lorry drivers’ strikes were especially disruptive – the biggest impact on me personally was missing school because there was no one delivering heating oil. At that time, competition from overseas hauliers was unknown. Now, no union has any control over distribution – not even the GMB which, after years of fighting for union recognition at Amazon, has finally managed to call a one-day strike at the company’s warehouse in Coventry on 25 January, demanding wages of £15 an hour.

Customers will be hard-pressed to notice the difference, but you can be sure the strike will speed Amazon’s determination to bring full automation to its warehouses – something which it said in 2019 was at least ten years away.

Across the whole economy, people work in much smaller blocs, partly through privatisation, but also as a result of the switch to a service-based economy. The Winter of Discontent was sparked not by public sector workers but by Ford car makers at Dagenham, who managed to squeeze a 17 per cent rise out of their employers, smashing through the 5 per cent ceiling that Callaghan was trying to impose across the economy. But the days of having 40,000 workers under one roof – the number in Ford’s Dagenham plant at its 1950s peak – are gone for good. Dagenham, these days reduced to producing engines rather than complete cars, employs just 2,000 workers.

It is little surprise, then, that there is no beer and sandwiches at No. 10 this time around. There may be a political benefit in that. The longer the strikes go on, the more difficult it becomes for Keir Starmer, who has already attracted ill will in his party by dismissing Sam Tarry, his deputy leader’s boyfriend, from the shadow cabinet for defying an instruction not to go on a picket line.

There is still a crisis in public services. It is just that in many cases it doesn’t have much to do with industrial action – even if the unions might like us to think it does.

Think, for example, of the ambulance service, already the subject of three 24-hour walkouts, with another planned for Monday. Unite and Unison, the two unions involved, have taken an especially hard line: in their December strike, ambulance staff in some parts of the country refused even to attend category 2 emergencies, which can include strokes and heart attacks. Yet it would be hard to distinguish between the lack of workers that day and the lousy service we suffer day in, day out anyway.

In October, before the strikes, ambulances were already taking an average of an hour to respond to category 2 calls – more than twice as long as they did even at the height of the pandemic in January 2021. The target for all NHS trusts is 18 minutes.

It is the same on the railways. The strikes have caused misery, but when does the rail system run smoothly any more? It was long before the strikes that Avanti West Coast reduced the number of trains between London and Manchester from three to one per hour. An even greater paralysis has gripped Transpennine services.

Paradoxically, some passengers have noted that services seem to be more pleasant on strike days – while trains are fewer in number, many travellers stay away. Who knows, it may be a case of non-union personnel being more efficient and effective than their unionised brethren.

As for Border Force staff, their attempt at a strike between Christmas and new year has exposed the inadequacy of their normal working practices. Many passengers have commented that airports have been running more calmly with the army doing the Border Force role. As one Guardian reader described arriving at Heathrow on a strike day: ‘It was easily the most efficient and stress-free journey through immigration we’ve ever had.’

We can’t, of course, rely on the army to fill in for bolshie civilian workers. But there are surely lessons to be learned from how employers have been forced to reorganise services on strike days. They should be asking themselves: are there emergency working methods that can be adapted and used more generally, perhaps leading to a leaner and fitter workforce in the long-term?

The British disease now is not union militancy, as it was in the 1970s, but low productivity. The two, of course, are connected. When your train is cancelled due to the lack of a guard you should be asking: why does my train need a guard at all, given that 30 per cent of all British trains run with a driver only – a form of operation introduced 40 years ago and which has proved every bit as safe, in spite of what the RMT tries to argue?

Strikes, though still irritating to many, have lost their power as a political weapon. The government is likely to get away with standing back from labour disputes. What it won’t get away with is failing to reform our creaking public services. To do this, it will have to risk upsetting the unions further. But it doesn’t really have an option in tackling the widespread sclerosis.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in