A dank Tuesday evening in a West End theatre. The auditorium is barely two thirds full. The play is nothing special – certainly not spectacular. Your neighbour is struggling to stay awake. The reception, however, is tumultuous. The audience is on its feet, squealing, whistling and whooping as though someone has just found the cure for cancer. The house lights come up and the rumpus stops as suddenly as it started. Everyone makes for the nearest exit.

This irritatingly mechanical ritual is a phenomenon – imported, I guess, from Broadway – that has recently become ubiquitous in London, never mind the quality of what’s on stage. It represents a significant departure from the custom of voiceless clapping, ranging in volume from warm forte to cool piano, that was customary during my youth 50 years ago. Nobody ever cheered or shrieked as Gielgud, Olivier or Guinness took their courtly bows; cries of ‘bravo’ or ‘brava’ were reserved for the curtain calls of the likes of Fonteyn and Nureyev at the Royal Opera House, and they were uttered in manly baritone rather than high-pitched squawk.

Why the inflation of response? Is the commotion caused by those who need to confirm to themselves that their time and money has been well spent? Does it indicate a need for physical release after a period imprisoned in darkness and silence? Or is it a genuine wish to honour the actors’ skills or celebrity? Whatever the explanation, there seems to be some primal urge at stake in this mode of signifying approval.

It is not, however, universal. There is no evidence, for instance, that the Greeks clapped at Epidaurus; Roman playgoers apparently only snapped their fingers or flapped their toga sleeves. We don’t know how spectators behaved at Shakespeare’s Globe, but there are hints that the audience’s response was continuous – ‘shouts and claps at ev’ry little pawse’ as the poet Michael Drayton put it – rather than held back for the conclusion. In Asia, it remains more common to applaud during a performance rather than after it – Indian kathakali is rhythmically clapped while the dancer is in motion, and in Noh theatre the rule is to shout a Japanese ‘well done!’ when an actor executes a gesture or speech with elegant artistry, but appreciation of the entire show is not usual. Wagner’s Parsifal trod such a thin line between grand opera and Christian sacrament that for many years it was greeted with reverent silence.

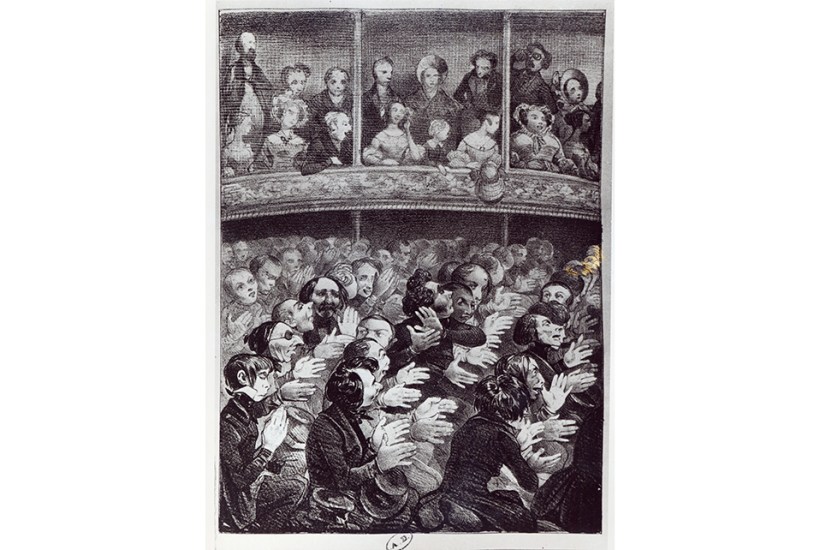

Putting your hands together, with occasional verbal interjections, has been the prevalent custom in Europe since the 18th century, though in Britain, the Theatres Regulation Act of 1843 curbed the uninhibited barracking and gallery catcalling that was the norm in the Georgian theatre. From the mid-19th century, play audiences gradually became more passive and polite, with numbered rows of seats and lowered house lights acting as further dampers. The older tendency to riot survives only in Christmas pantomime, which constantly breaks the fourth wall and licenses the audience to boo every appearance of the villain, warn the hero of perils if he looks behind him and even direct the course of action, as in the heartrending moment in Peter Pan when responsibility for the life or death of Tinker Bell hangs on children clapping.

Britain is largely free of a mafia-type menace that corrupts mainland Europe in the form of protection rackets that extort money from performers to vociferously cheer or boo at key moments in the show. Such claques are said to persist at La Scala, Milan, making the lives of several opera singers either an unmerited misery if they refuse to pay up or delivering them a factitious triumph if they do. But we are not guiltless either: if things look ‘slow’, theatre managements often plant staff members in the audience with the whispered instruction to make things go with a swing.

Applause is fed by the ceremony of the curtain-call parade, in which the actors file in one by one, abandoning their characters and resuming their real identities. That they should bow to their audience is a hangover from a time when actors were considered of servile social status, ‘craving the indulgence’ of their superiors and patrons. Today’s more democratic mores have led to a preference for a collective line-up in which the note of deference is replaced by one of celebration – weren’t we marvellous? Russian actors communistically think it proper to reciprocate the applause by clapping the audience.

But there is still some special excitement to be milked from a spotlit solo call for the star of the show – often accompanied by some feint of surprise and gratitude at the acclaim. Occasionally, if a role has been particularly demanding, such a performer will seem to remain shamanically possessed, not yet ‘returned’ to his or her self – I’ve seen this spookily happen in the opera house on occasion where a hyperventilating singer or dancer, still lost in their character’s tragic fate, genuinely doesn’t seem to know who or where they are.

Booing has become something of an issue in recent years, particularly in relation to the first nights of left-field productions of classic operas (it remains extremely rare in straight theatre). Directors bear the brunt of the onslaught, and many of them smugly relish the hostility. A new fashion for booing unpleasant characters such as Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly is merely infantile and insulting to the singer who appears at the curtain call as themself.

Things got even nastier the other month at Covent Garden. A 12-year-old boy was singing an aria in Handel’s Alcina when some lunatic yelled ‘Rubbish’ and started booing – at which the rest of the audience responded with supportive cheering. Horrible and disconcerting for the poor child, of course, but the sort of flashpoint that keeps the theatre electrically alive – there’s certainly something more authentic about it than those vacuous nightly West End standing ovations.

The post A short history of applause – and booing appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in