Friedrich Nietzsche may not be the most fashionable member of the conservative canon, but doubtless he wouldn’t care much. He knew that one of the main symptoms of a civilisation in decline is ‘herd thinking’. Regardless of the victor, this summer’s Conservative leadership contest has been a case in point for Freud’s narcissism of small differences. None of the candidates have dared deviate from the dogma of Thatcherism.

Grant Shapps said it loudest: like Thatcher, he would confront union ‘Luddites’ to save an ailing economy. Liz Truss wants to to ‘crack down’ on trade union ‘militants’ by making it harder for them to call strikes. Truss didn’t even need to name Thatcher as for some time she has been cosplaying as the Iron Lady. Not to be left out, Truss’s rival for the leadership Rishi Sunak held a campaign meeting in Thatcher’s hometown of Grantham, where now resides a statue dedicated to her memory.

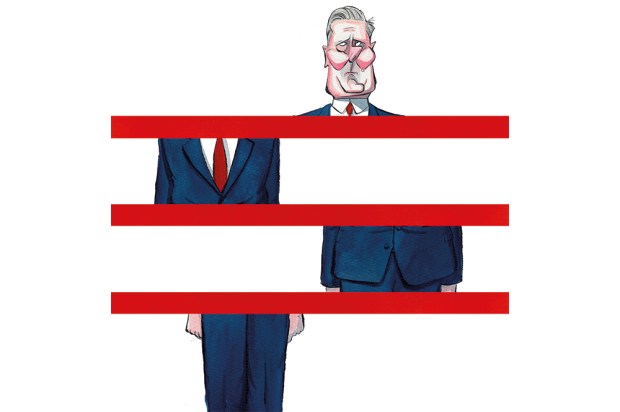

Sunak and Truss’s economic policies have not been judged by whether they are good, but by whether they can be deemed ‘Thatcherite’. Their differences are insignificant: they both agree that tax cuts, a smaller state and a more deregulated economy should be the party’s priority. Indeed, all candidates for the party leadership have sung this tune.

How healthy it this for a party facing the biggest economic crisis since the 1970s? Any anthropologist might point out however that invoking the departed in times of fear is historically never a good sign. Despite a diverse ethnic and cultural make-up, none of the Tory leadership candidates dared suggest that Thatcherism was anything other than perfect.

Truss was born the year Thatcher became leader and was still below the age of consent when she was deposed. In her mind, Thatcher has assumed a mythical status, one whose policies must be followed slavishly. This is despite the very different circumstances and challenges that Britain faces now compared to those which confronted Thatcher in 1979.

Just to take the example of the trade unions. In 1979, they accounted for almost half the workforce but today not much more than one-fifth. In the year before Thatcher became Prime Minister almost 30 million working days had been lost to strikes but the figure for 2018 was not much more than 250,000. While strikes could be called on a hand vote held on some spare ground in the pre-Thatcher period, now at least 50 per cent of all members have to vote in a strike ballot conducted by post before it can take place. This means that when a strike does occur it is has to be supported by the majority of members: the forthcoming postal strike led by the Communication Workers Union for example saw 99 per cent of its members vote in favour of taking action on a 72 per cent turnout.

Over the years, a few Conservatives have tried to reckon with the country they lead a little more honestly. In 2016 Theresa May reminded delegates at her first party conference as leader that:

Government can and should be a force for good; that the state exists to provide what individual people, communities and markets cannot; and that we should employ the power of government for the good of the people.

May’s agenda was blown off course by events, but she was not the first Conservative to see the state as an essential guarantor of security. In 1999 deputy leader Peter Lilley – someone most would see as a staunch Thatcherite – warned of the influence of ‘anarcho-capitalists’ in the party who ‘believe the model of autonomous individuals interacting by voluntary exchange without the intervention of the state can be applied to every aspect of human affairs’. There were great dangers of ‘equating Conservatism with free marketeering and nothing else’. Lilley was quickly consigned to the wilderness for such apostasy.

Despite Lilley, the ‘anarcho-capitalists’ now run the party and make up the majority of its membership. There is a deep irony that these herd thinkers invoke Thatcher to justify their by-now-hackneyed beliefs. For when she became – very unexpectedly – leader in 1975 it was partly because she stood against the mushy One Nation herd thinking of her day, one principally defined by Edward Heath’s attempt to make the post-war consensus work. Thatcher’s revolutionary zeal marked her as one of those exceptional individuals Nietzsche believed were vital to advancing civilisation and saving it from decadence. Such figures seem completely absent in today’s Conservative party, which for a party supposedly devoted to individualism, makes the irony all the more delicious.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in