In the classic Hitchcock film The Birds, there is an early scene where the protagonist notices a raven standing on the metallic scaffolds of a children’s playground. Then a few other ebony harbingers float down to join the solitary raven to form a small but portentous murder.

Salman Rushdie, author of The Satanic Verses (for which he was given a fatwa in 1989 by ayatollah Khomeini of Iran, who publicly offered money for his murder), said with a wry smile in an interview about 9/11, ‘I was the first bird.’

More than three decades after the fatwa, Salman Rushdie was stabbed multiple times by a likely religious fanatic in Chautauqua, New York, just before he was about to give a lecture about freedom of expression.

And yet, after three decades of death threats and a trail of blood leading up to this latest attempt to use violence to subjugate speech, many in the West still haven’t realised the frontal assault on liberty posed by the spread of extreme Islamism.

When the fatwa was announced, the zeitgeist in Western political, literary, and religious circles was disappointingly dastardly. Overtures were simpered against the proposition of violence, but many sneering, jeering, and deriding remarks were made to the effect that Rushdie ‘knew what he was doing’ and ‘had it coming’ for insulting a great religion.

It is irrelevant that the primary intention of the novel was not to insult Islam. Most people in the Islamic world (and seemingly among the chatterati in the West) haven’t bothered to read the book.

Among those who failed to defend Salman Rushdie following the fatwa were many British politicians from both sides of the house along with Jimmy Carter, the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, writers Norman Podhoretz, John Berger, Roald Dahl, and John le Carré, and religious leaders such as the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, the Chief Sephardic Rabbi of Israel, and the Vatican.

This was in the light of the following: bookstores having been bombed, attempted murders on Rushdie carried out, who was forced into permanent hiding with police protection, the murder of his Japanese translator Hitoshi Igarashi, and the attempted murders of his Italian translator Ettore Capriolo, who was stabbed in his home in Milan, and his Norwegian publisher William Nygaard, who was shot in Oslo.

The Egyptian author and Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz was one of the very few voices supporting Rushdie from the Islamic world. As a result, he was stabbed in the back by a fundamentalist.

Luckily, some writers were brave enough to voice their support, including Christopher Hitchens, Martin Amis, Susan Sontag, and Arthur Miller. A heartening book, entitled For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech was also published in 1994 and contains pieces by luminaries such as the Syrian poet Adonis and the Syrian-Kurdish author Salim Barakat. Courageously, 127 Iranian writers, artists, and intellectuals signed their names in a letter denouncing the Iranian fatwa and defending artistic liberty and the freedom of speech. With their help, Rushdie kept writing. He told his friend and staunch defender Christopher Hitchens that his biggest fear was that living like a fugitive would kill his creativity, but it evidently did not.

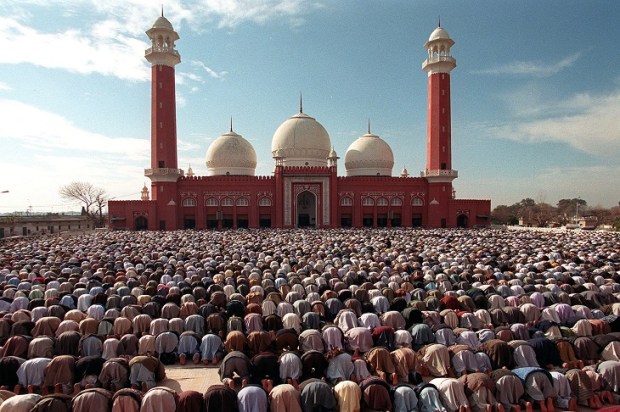

Since the Rushdie affair, countless examples of bloody attempts to curtail the freedom of speech have been made by Islamic fundamentalists in the West and, importantly, in the Muslim world. It is always worth underlining that the majority of victims at the hands of Islamic fundamentalists are those the West considers ‘minorities’. The crimes of the Islamic State, including the attempted genocide of the Yazidis in northern Iraq during the mid-2010s, are plain to see. Inhumane deeds, like the mass beheading of 150 women for refusing to marry IS militants, are too horrific to conceptualise for most. The Taliban shot 15-year-old Malala Yousafzai in the head for daring to speak up about education for girls. The Peshwar school massacre resulted in 132 dead school children. The Islamist group Boko Haram (meaning ‘education is forbidden’) has committed spates of kidnappings, slaughter, rapes, and tortures in Nigeria. Recent estimates put the toll at 300,000 dead children.

In the West, it is astonishing that so many intellectuals and institutions cannot bring themselves to stand whole-heartedly against this vicious extremism. A combination of misplaced and simplistic white-guilt and naked fear has meant that freedoms are ceded to Islamists inch by inch, through self-censorship.

If Rushdie was the first bird, the next birds will quickly join the melancholy flock.

In 1993, the Sivas massacre saw the death of 35 intellectuals in Turkey. Among them was Aziz Nesin, who had tried to publish The Satanic Verses.

The Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh was killed and ritually beheaded in 2004 for making a film with Ayaan Hirsi Ali that is critical of the way women are treated in Islam. Ali, a refugee from Somalia who became a parliamentarian in the Netherlands, was forced to seek asylum in the America as the Dutch government thought the continued threats and actual attempts on her life, as well as other politicians such as Geert Wilders, were causing too much trouble. As Rushdie pointed out, Ali may be the first refugee to have fled Western Europe since the Holocaust.

The Muhammad Cartoon Crisis in 2005 shook the world. The Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published 12 cartoons, most depicting Muhammad. Danish Imams fanned up hatred in the Middle East by presenting fake cartoons along with the real ones, including one fake where Muhammad was represented as a pig. This led to riots and attacks on Danish embassies and some 250 deaths. Ironically, the cartoons were commissioned to highlight the already strained relationship Danish society had with Islamic immigrants, triggered by the story of an author who wished to write a children’s book introducing Islam to Danish children in a gesture of multiculturalism, but who was unable to find an illustrator for fear of reprisals. Still, the intellectual set was largely unable to simply denounce the violent extremists.

Hitchens summed up the sentiment in Slate perfectly: ‘Let’s be sure we haven’t hurt the vandals’ feelings.’

In 2015, almost the entire editorial office of Charlie Hebdo was murdered by two al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula terrorists for publishing satires of Muhammad.

This is without mentioning recent large-scale attacks on the wider population, such as the massacres in Paris and Nice, or the Manchester bombing. In all these cases, the institutions and intellectuals, instead of showing outrage and courage, shrank further back. Instead of an ‘I am Spartacus’ moment, those like Rushdie, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and others have been left exposed, bearing the weight of defending freedom of expression.

Even worse, in recent years many institutions have actively started doing the censor’s work. For example, in 2016, the Southern Poverty Law Center labelled anti-extremism campaigner Maajid Nawaz and Ayaan Hirsi Ali as ‘anti-Muslim extremists’. This in spite of Ali being born a Muslim and Nawaz still being a practicing Muslim.

Obama was exactly wrong when he said in 2012 that the ‘future must not belong to those who slander the prophet of Islam’. The future must belong to those who are able to question any authority, deemed holy or satanic, and ignoring so-called ‘hurt feelings’. A free society is the only society worth having.

Luckily it seems that Rushdie will survive, although likely to lose an eye. Martin Amis once wrote brilliantly that Rushdie’s eyes reminded him of a hawk peering through Venetian blinds. The author, who has shown tremendous courage in the face of death and who has refused to live in fear, will hopefully carry on, casting his remaining eye defiantly at those who have failed to make him submit, and inspire more to find a little courage of their own.

In his words: ‘How do you defeat terrorism? Don’t be terrorised.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in