‘Our generation owes an apology to the shades of Harold Wilson,’ the polling guru Peter Kellner once told me. Had Wilson not firmly resisted pressure from President Lyndon Johnson to send troops to Vietnam, Kellner and I were both old enough to have fought there. But in 1968 we loftily despised Wilson for twisting and turning to stay out of Vietnam and keep his party together. ‘What are the two worst things about Harold Wilson?’, we asked. ‘His face,’ we replied smugly.

Britain has never quite forgiven Wilson for his cleverness. His reputation suffered a catastrophic decline in the immediate aftermath of his premiership. It was partially rescued by Ben Pimlott in his 1993 biography, though even he saw Wilson as a mere tactician, albeit a very good one.

Nick Thomas-Symonds’s new biography shows us a Wilson we do not know: a visionary, ‘a kind and generous man’, driven by his father’s long periods of unemployment to make a better world. He never forgave himself for asking his father during one such stretch for three shillings and sixpence to buy a scout knife. ‘I can’t just now – you know how things are,’ mumbled the embarrassed parent.

Then we get the Oxford undergraduate, quiet, studious and brilliant, who becomes an Oxford don at 21. He did very little politicking or socialising, and the Bullingdon Club would have called him a girly swot. After that comes the wartime technocrat of something like genius, with a grasp of detail and political reality which took him into politics in 1945 – an MP at 29 and president of the Board of Trade at 31, the youngest cabinet minister of the 20th century.

Finally, we are shown a great reforming prime minister: ‘Had Wilson achieved his ambition of introducing economic planning, he could have stood alongside Attlee.’ Wilson defined left-wing politics for a generation. The famous 1963 ‘white heat of technology’ speech and his scorn for the old boy network made him the voice of the future, not just for his party but for his country too.

Solid achievements included the ‘university of the air’, which became the Open University. This was Wilson’s personal vision, and without him it would not exist. His first government, as Thomas-Symonds puts it, ‘improved the status of women in the workplace, took away the need for backstreet abortions and allowed couples to escape unhappy relationships without an unfair penalty for the female spouse’.

His Health and Safety at Work Act of 1974 has probably saved hundreds, perhaps thousands, of lives. His 1975 Employment Protection Act brought in the UK’s first legally enforceable maternity leave and created the industrial relations conciliation body ACAS. Wilson’s governments made it illegal to advertise for ‘women’s appointments’ or for hotel managers to refuse to serve women unaccompanied by a man, and his Race Relations Act outlawed racial discrimination. ‘These changes, achieved in a House of Commons without a substantial majority, were a considerable achievement’, writes Thomas-Symonds.

A less determined or deft prime minster might have failed to keep us out of war in Vietnam or Rhodesia. His referendum (a constitutional innovation which has had a mixed press) made Britain’s presence in the European Economic Community (as it then was) as permanent as any political achievement ever is. Wilson told an adviser: ‘Pulling out of Europe would put the wrong people in power in Britain, like Tony Benn and Enoch Powell.’ Substitute Jeremy Corbyn and Boris Johnson for Benn and Powell and you see Wilson’s political brain at work.

Along the way, Thomas-Symonds demolishes a few myths put about by Wilson’s many enemies. He never claimed to have gone to school barefoot. He never had an affair with Marcia Williams – unlike his detractors, Wilson could value a woman for her brains. And he didn’t invent a plot by the security services to undermine him. It didn’t need inventing: it existed.

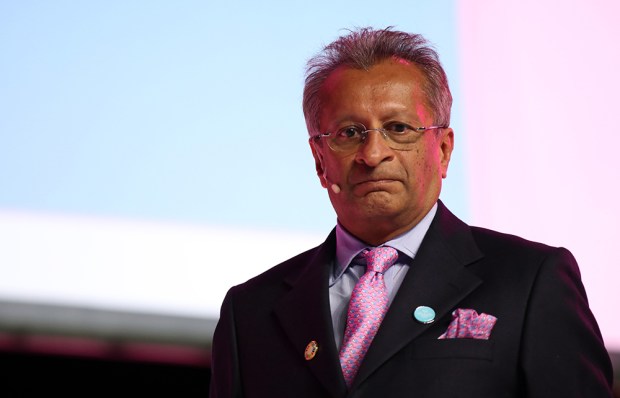

Wilson is Keir Starmer’s political hero, and Thomas-Symonds is a seriously clever young politician whom Starmer is preparing for high office in a Labour government. Still only 42, he has been a successful barrister, biographer and Oxford historian: he is a brainy polymath, just as Wilson was.

This comprehensive, carefully researched and very readable biography aims to establish Wilson’s place in history – not as the neurotic schemer often reported during his sad last years, which were blighted by dementia, nor even as the supreme political fixer portrayed by Pimlott, but as a decent, honourable man, as well as a very clever one, who was in politics to do something, not just to be someone. He was, Thomas-Symonds concludes, one of our greatest prime ministers, who, given the political circumstances, had a remarkable record of solid achievement.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in