The Japanese government has launched an initiative to encourage young people to drink more alcohol. Yes, really. The national tax agency’s ‘Sake Viva’ campaign is an appeal for ideas to get youngsters boozing after taxes on alcohol products, which accounted for 5 per cent of total revenue back in the hard-drinking 1980s, fell to just 1.7 per cent in 2020. So, at a time of economic hardship, Japan’s youth are being asked to do their patriotic duty and get hammered.

The falloff in social drinking is being attributed in part to the pandemic. Japan didn’t have a full-blown lockdown imposed from above, but the more subtle bottom-up lockdown that demonised anyone frequenting bars and restaurants worked pretty well. With the Japanese media still obsessive about case numbers, people live in morbid fear of bringing an infection into their office, or perhaps, university. If they do, and it were ascribed to an indulgent night on the town, they could find themselves ostracised: there are reports of the recovered returning to the office and being forced to work on their own. A night on the town just isn’t worth the perceived risk.

But Covid doesn’t quite cover it. The new abstinence has deeper roots. Ever since the early 1960s, when the crime-ridden neighbourhoods of Japanese cities were replaced by forests of high-rise towers, the Japanese have mirrored their newly pristine environments by steadily becoming comically law-abiding, obsessively health conscious and scrupulously risk averse.

The Yakuza mobsters are now virtually extinct, crime is negligible and Japanese police hang around with very little to do except keep watch (which helps ensure they continue to have very little to do). Japanese life expectancy remains the longest in the developed world, with a new record of 86,000 centenarians achieved recently. Safety messaging is a booming industry: everywhere you go, you are urged to take care, hold on to the handrail, mind the closing doors and put one foot in front of the other when you walk along the road (not really but perhaps not far off).

There is little place in modern Japan for boozing, smoking, or anything else that smacks of slightly risky self-indulgence. The young show no inclination to rebel. As a university lecturer, I work daily with Japanese teens and marvel and wonder at their glowing health, modest appetites and lack of obvious vices. No one is overweight and no one seems to drink. Neither tobacco nor the sickly-sweet aroma of cannabis is ever encountered on campus. Few seem even to have partners. The Adam Ant lyric ‘you don’t drink, don’t smoke, what do you do?’ comes to mind.

All of this selfless inactivity is not just threatening treasury revenues but, some believe, the very existence of the Japanese people. ‘Celibacy syndrome’ – the hypothesis that Japanese young people are having less and less sex gained a lot of media attention a few years ago. The ‘no sex please, we’re Japanese’ meme may or may not be true – it’s the kind of ‘weird Japan’ story that the media pounces on – but the Japanese are certainly not having children. The birth rate is the lowest in history, probably due to an excessive culture of caution meeting uncertain economic times. The numbers are frightening: Elon Musk has predicted that unless something changes, Japan will eventually ‘cease to exist’.

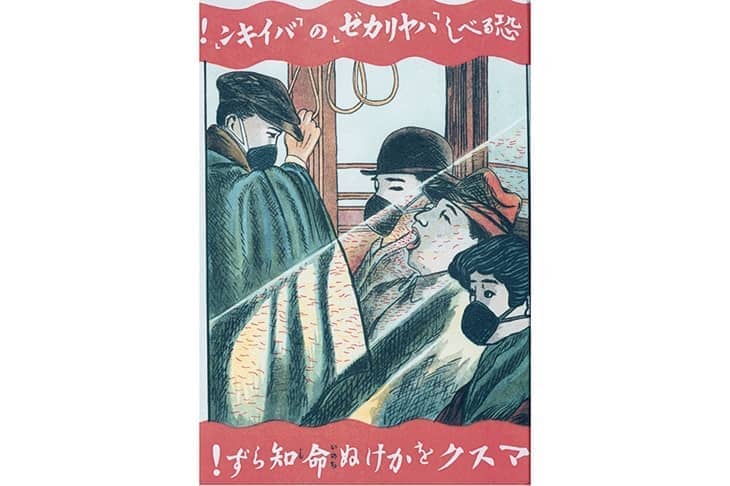

Extreme safetyism is also seen in the Japanese people’s stubborn refusal to give up their face masks, despite being urged to do so by the government earlier this year. The health ministry pointed out that however dangerous people think Covid might be, wearing cloth coverings in 40ºC heat in a country with a high percentage of geriatrics was undoubtedly worse. Nobody took any notice. A record 15,000 people were hospitalised from heat stroke in June.

Much has been made of the various odd cults that wield influence in Japanese society. None are as powerful as the faith in safetyism. Exacerbated by a hermit-like lingering fear of Covid, a return to the heady days of heavy drinking seems far off. The government’s campaign is doomed to failure.

The seriousness with which the Japanese take their health and the health of others is admirable. But it can be self-defeating, and is also, dare I say, a little boring. I am reminded of a conversation I had with a gloomy young kikokusei student (a Japanese native who has returned from living abroad). He told me how much he missed America and how he couldn’t adjust to life back in Japan. I tried to lift his spirits by pointing out some of Japan’s undoubted plusses, including, of course, the safety.

‘Yeah…’ he drawled, as if he’d heard that argument one too many times, ‘but it’s too damned safe.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in