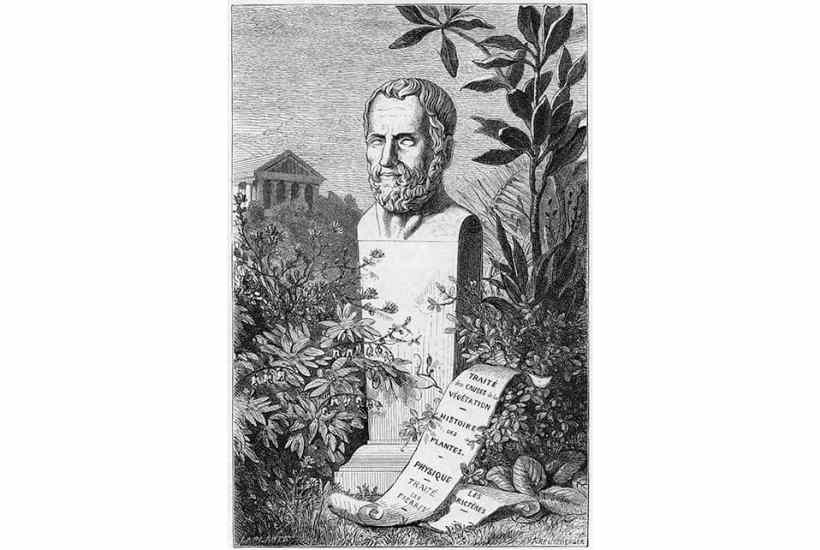

Publishers lately seem to have got the idea that otherwise uncommercial subjects might be rendered sexy if presented with a personal, often confessional, counterpoint. The ostensible subject of Laura Beatty’s book is the pioneering Greek botanist and philosopher Theophrastus. He was a friend of Aristotle’s, and was once thought his intellectual equal, but is now little known except to a few classicists and historians of science. But since no one wants to publish a straight book on Theophrastus, we get instead a book that is at least as much about Laura Beatty, her library researches, her travels in Greece and her kitchen garden.

Her publishers describe the book as ‘genre-defying’. But the genre lines can be blurred only so often before we have simply created a new genre, with all the clichés that come with it: how Middlemarch cured my midlife crisis, retracing Nietzsche’s morning walks, what Mrs Gaskell taught me about love… you know the sort of thing. Works in this genre have rarely managed to answer the basic sceptical question they raise: if I’m not already interested enough in Theophrastus to pick up a book about him, why would I be any likelier to pick up a book on him because it also features the sentimental journeys of a certain Laura Beatty?

Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage remains a model of how to do it, if you must. The memoir there really earned its keep, with D.H. Lawrence’s personality brought into sharp relief when evoked in the voice of its crotchety, distractible narrator. Dyer solved the problem of how to draw in the Lawrence sceptics by being provocative, perceptive and extremely funny. Would that his imitators had learnt that lesson.

To be clear, Beatty’s book is not by any means the worst entry in this genre. The passages of travelogue are relatively brief, the Paddy Leigh Fermor flourishes kept firmly under control. She is an earnest and persuasive champion of a minor Theophrastan work, The Characters, which she praises for its novelistic insight into human psychological types. She quotes intelligently and often at length from Theophrastus himself, allowing us to watch him grapple with the foundational problems of a science in its infancy. How to classify, without distorting, the bewildering variety of nature? Should we go by form or function, appearance or inner structure, behaviour or habitat? How to distinguish folk superstition from canny proto-scientific explanation?

‘Imagine a world,’ she instructs us, ‘where nothing yet has an explanation and where life is springing up everywhere and all the time, in dazzling variety and profusion, and through processes that are as yet undiscovered’. If her aim was to rescue Theophrastus’s work from the enormous condescension of post-Linnean botany, she has succeeded admirably. But that excerpt also indicates a weakness for purple prose, one all too frequently indulged.

Any reader wishing to look up a quoted passage will struggle to find a full reference – omitted, apparently, ‘for reasons of space, and because this isn’t an academic work’. The undisciplined historical speculation, the barely sourced excursions into psychobiography, are defended as part of an effort ‘to tell a story’. I could find no way to distinguish between the historical claims presented as straightforward truth and those hedged with a dainty ‘supposed to have’. Beatty engages in many a prolonged bout of handwringing about the old problems of biased sources, ambiguous texts and the limits of objectivity. But despite her passionate vocatives (‘What were you doing, Theophrastus?’), she appears to think that admitting effusively that those problems exist is enough to settle one’s accounts with them.

The philosopher Bernard Williams once prefaced a book on Greek tragedy – not his academic specialism – with the acknowledgement: ‘There is no reliable way of converting the disadvantages of amateurism into the rewards of heroism.’ Beatty’s book is self-confessedly the work of an amateur, with all the word suggests of bumbling and (as its Latin root indicates) of love. But love can shade easily into an unseemly familiarity: ‘So tell me’, ‘I share your love of plants’, ‘Look at my seedlings, Theophrastus’. In any case, the results are far from heroic.

Theophrastus revealed himself to us by showing an interest in people and plants and politics – that is, in things other than himself. Beatty rightly wants to treat him and his world ‘as something vitally connected to today’. But she tries to do this by telling us just how much that past means to her personally. Iris Murdoch, who shared that attitude to the Greeks, cautioned us that ‘bad writing is almost always full of the fumes of personality’. Beatty would do better by the man she affects to love if she’d get out of the way and let us take a good look at him.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in