To be an anthropologist today is to understand, as few in the secular modern university can, what it is to be marked by a consciousness of original sin. Contemporary ethnographies are full of passionate mea culpas from scholars concerned that they have inherited the guilt of their discipline’s founding fathers, men who inhabited a world of red-cheeked missionaries and pith-helmeted viceroys.

Lucy Moore is not the most natural candidate for a historian of the discipline. Her back-catalogue shows her to be a generalist and belletrist – a book on the Roaring Twenties, one on Indian princesses and another on Georgian rakes. Her prose is fluent and soothing, her narratives informative without being especially taxing, their outlook humane but never subversive.

‘I’m concerned with life stories,’ she writes in the introduction to In Search of Us, ‘not academic critique.’ The life stories in her book are those of 12 European and American anthropologists from the 1880s to the 1930s. Her chronicles begin with ‘The Pioneer’ Franz Boas on Baffin Island marvelling at how many words the Inuit had for snow and end with ‘The Trickster’ Claude Lévi-Strauss in Brazil, turning the ethnographic gaze back at the anthropologist himself. She wants to address what a previous historian of the subject termed ‘the central question of intellectual history’: ‘What was bugging them?’

The question helps her to bring under control what would otherwise be a surfeit of material. The results are certainly entertaining, the stories told with a novelistic eye for the character-revealing anecdote. But the book also has an air of frothiness, which might come of the fact that Moore never gets enough of an individual angle on the story to make this history distinctively hers.

Some of Moore’s writerly tics can be passed over easily enough. She tends to register a point of controversy with a sheepish ‘arguably’ rather than staying actually to argue the point. She can lapse into clichés (‘tropical paradise’), and muddles up ‘refute’, ‘rebut’ and ‘repudiate’. Her need to apologise or explain every time one of her dramatis personae speaks of ‘savages’, ‘barbarians’ or ‘primitives’ starts to wear a little. Surely no reader uncharitable enough to need these repeated reminders that the past is a foreign country will be much mollified by them.

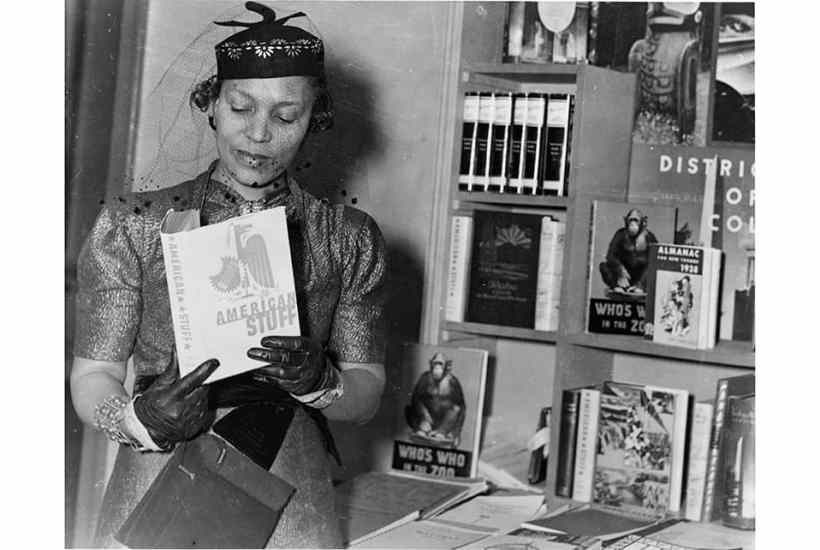

Against these lapses, one can bring up Moore’s judicious choice of personae. The dead white men (Franz Boas, William Rivers, Edvard Westermarck, Alfred Radcliffe-Brown) are painted in all their contradictions: rigorous and selfless as often as they are narcissistic and mercenary. Moore accommodates the discipline’s founding mothers too – Daisy Bates, Ruth Benedict, Audrey Richards and (of course) Margaret Mead all put in a showing, as does the unclassifiable, mercurial Zora Neale Hurston.

Her characters are all doughty fieldworkers, risking sunburn, malaria and ridicule to get their data. The field is where they make their careers, but its anonymity and distance from the norms of their own societies makes it also a place for them to undertake other sorts of (bisexual, adulterous) experiments in living. All this is told without judgment or moralism, just as her characters would have wanted.

Moore recognises rightly that the pioneering anthropologists saw their refusal to judge other cultures as part of an argument ‘for greater understanding and generosity of spirit’. But one wonders how much more interesting her book might have been if she had put that very argument under some pressure. What, for instance, of the old concern that the liberalism of toleration might itself be a cultural product?

The anthropologist Robert Lowie is paraphrased as saying: ‘The corollary of the idea that one must not impose moral evaluations on the subjects of an enquiry is that one must not impose moral evaluations on anyone.’ But of course, this is not a corollary at all, not unless we fallaciously confuse a methodological precept for a moral one; we are not all always doing fieldwork.

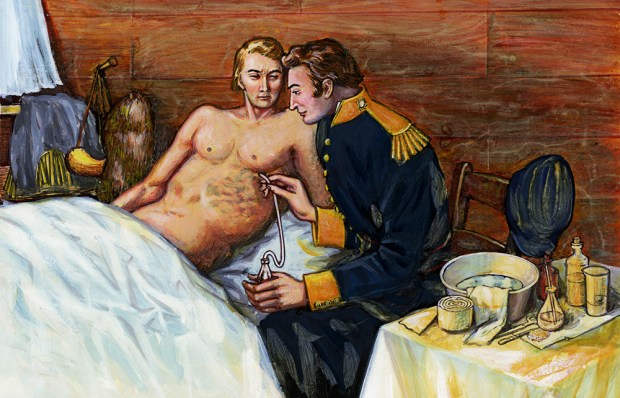

Lowie seems to have held that anthropology should no more denounce the practices of another culture (cannibalism, infanticide, clitoridectomy) than a zoologist should denounce ‘the wickedness of a rattlesnake’. The analogy is confused: taken at face value, it denies precisely what anthropologists in their liberal universalism were rightly anxious to show – that the ‘savages’ they met in the field were fellow human beings and not animals.

Some concern with such problems might have provided Moore with a source of friction, something ‘bugging’ her as she conceived her history. Ruth Benedict is quoted in these pages as describing the virtues of the anthropologist (‘a certain tough mindedness and a certain generosity’) in terms that serve equally well to describe the ideal historian. But the balance is all: I should like Moore to have shown her subjects and their discipline a little less generosity, a little more tough-mindedness.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in