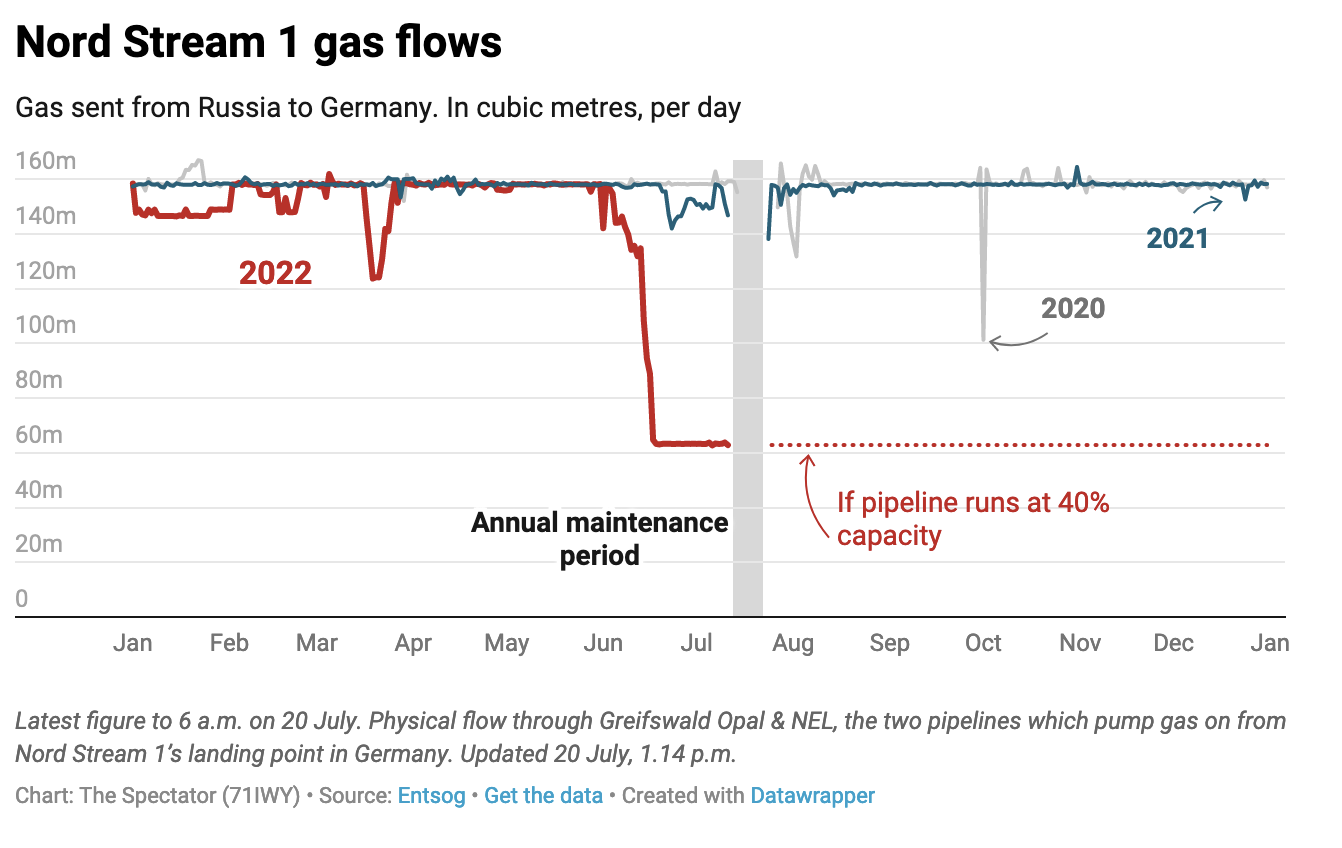

For now, Berlin can breathe a sigh of relief: after a ten-day shutdown for maintenance, the Nord Stream 1 pipeline is back online. Russia is once again heating German homes, fuelling German industry, and using German money to finance its war in Ukraine. But this happy exchange may not continue; the pipeline is still operating at just 40 per cent of its usual capacity, and Vladimir Putin is warning this could fall to 20 per cent next week.

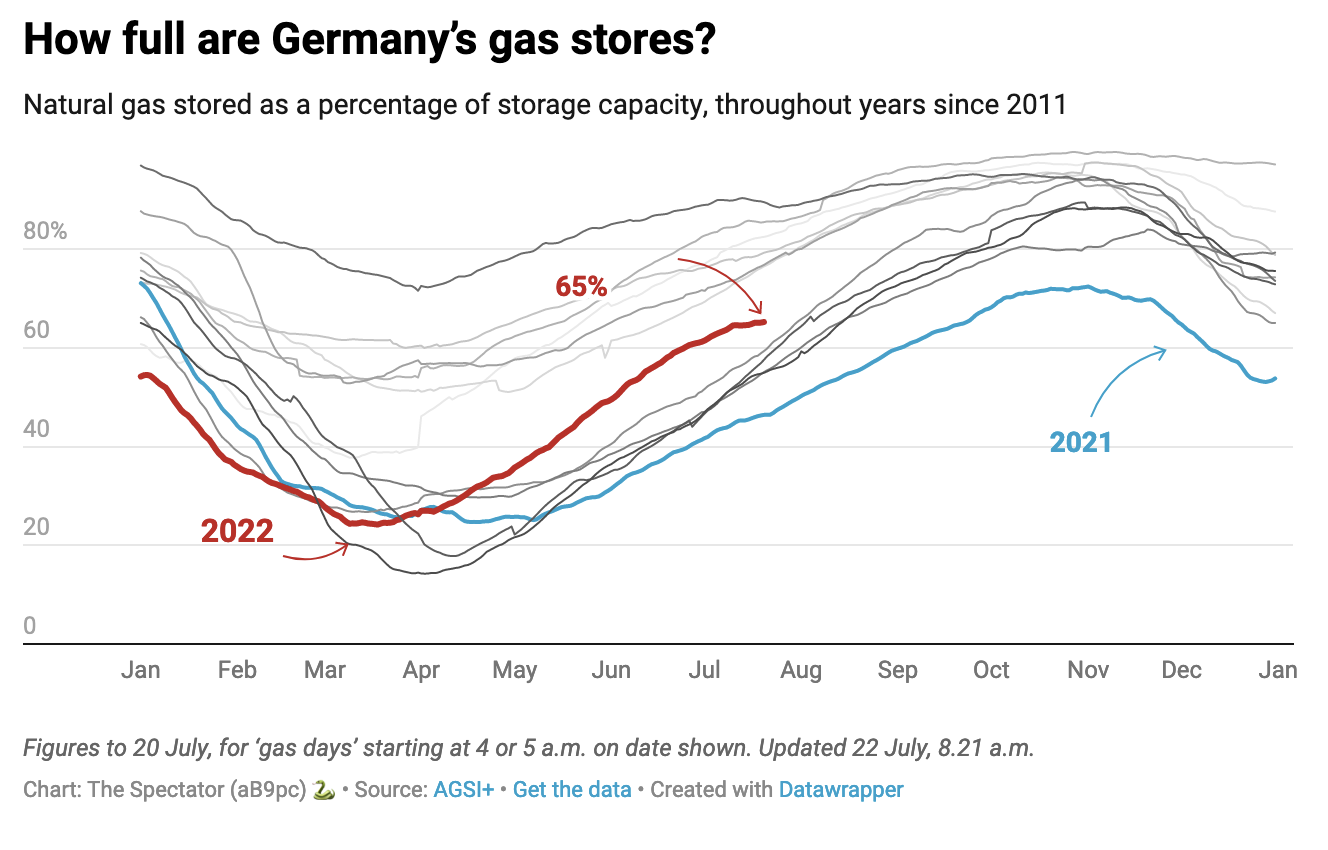

With Germany’s gas reserves just 65 per cent full – thanks in part to state-owned Russian energy company Gazprom’s curious oversight in maintaining them last year – and plans to refill it strained by Putin’s control of the gas flow, there is genuine concern that Germans could find themselves facing a brutal energy crunch this Christmas.

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen has warned that ‘full disruption of Russian gas’ is ‘a likely scenario’, so the EU is recommending a 15 per cent cut in gas consumption, which would become binding in the event of a significant reduction in flow.

Responses from the south of the continent to the proposal have been frosty, to say the least. After years of grinding their teeth while Teutonic politicians berated their fiscal profligacy, Spanish ministers are finding more than a little schadenfreude in Berlin’s misfortune. Teresa Ribera, minister for ecological transition, responded to demands for pan-European cuts in energy use by remarking that ‘unlike other countries, we Spaniards have not lived beyond our means from an energy point of view’.

Even if the EU’s mechanism does come through, it won’t be enough to prevent significant economic pain. A winter of low fuel will force the government into rationing, and industry is likely to lose out to residential consumption. The mechanical engineering association VDMA has described the current policy as ‘private households have priority and industry will just have to make do’, warning of significant drops in production if carried out. The chemical industry is particularly vulnerable; it uses 15 per cent of Germany’s gas consumption, and the association VCI has warned ‘there’s not much more we can save’.

Britain won’t be insulated from a crisis on the continent. There are three main channels through which a German fuel crunch would hurt the UK economy: energy prices, demand for exports, and disruption to supply chains.

While Britain doesn’t import gas from Russia, it’s still exposed to price swings in the marketplace. Norway is the single largest source of gas used in Britain, and also a major supplier to the continent. Prices are fundamentally a mechanism for allocating scarce resources; when demand from one group of users rises, others have to pay more to secure their supply. If Russia shuts down fuel supplies to Germany, prices in Britain will soar – driving up energy bills, and damaging heavy industrial users.

The second mechanism is also simple. Britain exports somewhere around £47 billion worth of goods and services to Germany every year. If Berlin is tipped into the ‘worst crisis since the second world war’, it’s safe to say demand for British cars and aircraft will suffer, and with it the fortunes of domestic manufacturers.

The third is more complicated. If Germany does find itself shutting down industries wholesale, it will send shockwaves through European supply chains. Here’s one example: Germany is the single largest supplier of imported parts and components for the UK’s automotive industry, supplying in the region of £4 billion a year. If this shuts down, then British manufacturers will have to scramble for new sources compatible with their current designs. Similarly, the Chemical Industries Association states there are 141 chemicals where Germany supplied 50 to 100 per cent of the UK’s total imports. It will be difficult to reshape supplies in time to avoid disruption.

This interconnectivity is what makes evaluating the effects of lockdown so difficult. This isn’t a standard recession driven by a lack of domestic demand: the supply simply isn’t there to maintain output. These effects ripple through complex supply chains that very few people understand within a given industry, let alone outside it. This complexity is why the UK manufacturing body Make UK believes it would be ‘impossible’ to estimate the extent of the disruption from Germany shutting down, although it does note there is some cause for optimism since the pandemic forced firms to decrease their reliance on single providers.

These effects would play out in supply chains across Europe, causing an extended period of disruption, with further knock-on effects for the UK. With Britain’s already spiralling inflation and soaring energy prices, a German recession and further supply chain disruption is the last thing our recovering economy needs.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in