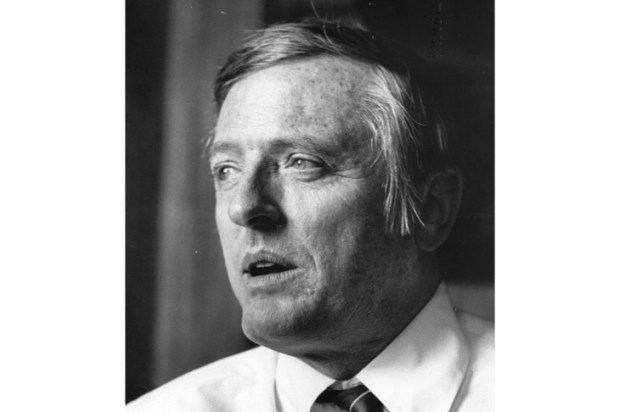

June 16 was Bloomsday, the day we celebrate James Joyce’s Ulysses, and it was a special Bloomsday because 2022 is the centenary of the publication of the book. During the time of the pandemic – or rather in the breaks from the lockdowns – Ronan McDonald the Professor of Irish Studies has been conducting a series of seminars at Melbourne University’s Newman College with the backing of the Rector there, Father Frank Brennan SJ. Frank himself had Covid last week and could not be there in person for the Sydney funeral of his father Sir Gerard Brennan, sometime Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia who wrote the Mabo judgment and changed forever this country’s relation to the Aboriginal people. But Frank was Zoomed into Saint Mary’s church in North Sydney where everyone from Pat Dodson, who spoke, to John Howard, was in attendance, everyone from Noel Pearson (who was thought of once as a potential indigenous prime minister) to that black-letter lawyer Ken Hayne. And among those there was Mick Crennan who had taken me to the Newman Ulysses seminar and who not only wrote a master’s thesis about Ulysses but at the age of 60 farewelled the Bar and proceeded to write one about the Roman historian Tacitus, as great a stylist, though a more uniform one, than Joyce. Cate McGregor likes to quote, ‘He created a desert and called it peace.’

Mick Crennan’s Ulysses thesis was written in the days when Sam Goldberg – privately known as the arsehole of God – ruled the Melbourne English department with a rod of iron. His very distinguished study of Ulysses, The Classical Temper, had as its epigraph D.H. Lawrence’s remark that some books were great even though the author laid it on thick.

Goldberg was a disciple of F.R. Leavis, the Cambridge critic people flocked from around the world to study under. Goldberg had written about Joyce at Oxford and refused to re-write but it was the poet-Professor Vincent Buckley who had been taught by Leavis and who supervised Mick Crennan.

The academic world is in danger of giving up even on Joyce, the English language world’s contender in the modernism stakes, as T.S. Eliot, the master critic of the day, whose The Waste Land was also published in 1922, realised was the writer who could hold a candle to Proust.

But this makes it all the more cheering that Bloomsday papers given on Joyce by the kids who are reading through Ulysses with Ronan McDonald were full of the intelligence and sensitivity that characterised the best critical traditions of Melbourne.

Manning Clark used to write in his old-fashioned essentialist way about how the Australian character came out of the tension between the English idea of uprightness and the Irish sense of humankind as part-larrikin, part-saint.

Certainly the pubs of Carlton and Fitzroy seem to chime with the Dublin Joyce evoked. I once found myself intoning about the glories of Ulysses for an ABC TV arts program shot at Percy Jones’ hotel on the corner of Lygon and Elgin Streets. I had just finished my speech when the six-foot-six former Carlton ruckman came out with a huge cry of ‘Hooray!’ Needless to say, it went to air.

Fortunately Joyce had a sense of the holiness of human foolishness. How a foolish gabbling gravedigger could hand Hamlet the skull of ‘Yorick, the king’s jester’ and provoke him to make that speech about ‘infinite jest’ which David Foster Wallace, one of Joyce’s heirs, would take as the title of his master work.

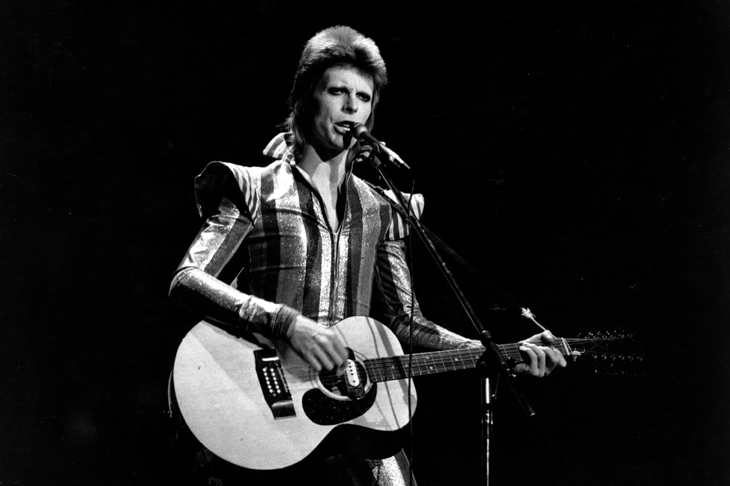

How strange the connections between things can be. 16 June 1972, fifty years ago, was when David Bowie released Ziggy Stardust, one of the most striking and spectacularly distinctive albums in the history of rock music. Remember the dash and dazzle of the way Bowie could create and confound those personas he paraded? He says of Ziggy, ‘He could lick ‘em by smiling’, and, at the height of his powers, he could turn these performative versions of himself into things of great poignancy. Remember on the Ziggy Stardust record that elegy, ‘Rock and roll suicide’? No one in the history of rock performance – not Dylan, not Mick Jagger or Lou Reed – had the electrifying command of the theatre of music that Bowie had. At the Myer Music Bowl half a century or so ago, 50 feet in the air, he could have been a god or a spaceman.

As the tragedy of the Ukraine continues, imagine the predicament of Alexei Ratmansky, the choreographer of the Australian Ballet’s Harlequinade. He is the former head of the Bolshoi and he is Ukrainian. He has asked for his ballets to be withdrawn from the Bolshoi and the Marlinsky, to no avail. He disagrees with Mikhail Baryshnikov who thinks the arts should not be used politically. Now he is doing Harlequinade in Melbourne and on 23 June and 25 June one of the greater dancers in the world Daniil Simkin will appear in the title role. Ratmansky is intent on capturing the sense of vulnerability within this choreographic reinvention of a commedia dell’arte bit of folderol. All that precision and comedy and pathos.

It’s easy to forget how deep the Ukrainians run in Russian culture. Gogol, one of the greatest of all ‘Russian’ masters – Dostoyevsky said, ‘I came out from under that overcoat too’– was from the Ukraine. So was Isaac Babel, the author of Red Cavalry, and so was that great inheritor of Gogol’s dreamscapes, Mikhail Bulgakov, the author of The Master and Margarita with its Jesus/Pilate story and its great sinister cat. The Ukrainians are the Russians’ Irish – not quite the same, not quite different. They have been forced into a separate nationality by atrocity but it’s a shared culture.

The Irish (or at least an American version of them) were a godsend the other night. The Fear Index adapted from Robert Harris’ cerebral thriller was a nightmare but after finishing it Wild Mountain Thyme (originally adapted from a play by John Patrick Shanley, the author of Doubt) was wonderfully soothing blarney and tosh, with Emily Blunt the most gorgeous of colleens, Jamie Dornan as a melancholic chap and the great Christopher Walken as an old mischief-maker.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in