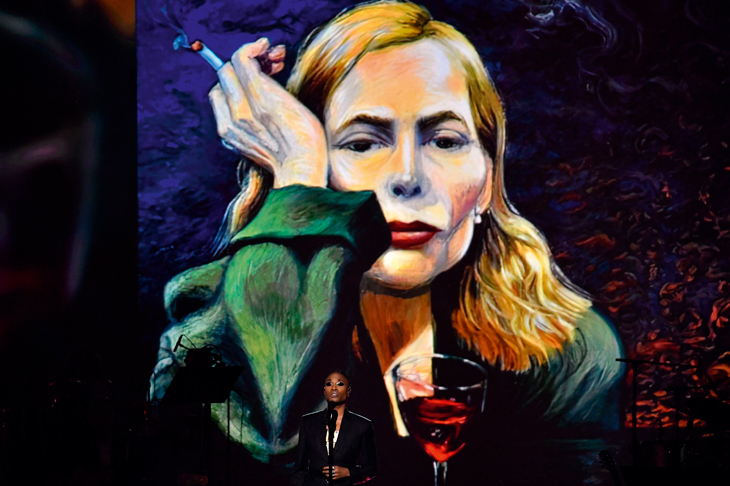

It’s a strange thing the way we keep interpreting and re-interpreting the different aspects of our culture that have become classics for us. The other day a notification that the award-winning chanteuse Queenie van de Zandt was about about to begin a national tour of Blue, a show in honour of the fiftieth anniversary of the Joni Mitchell album of that name. For a brief electrifying moment this was mistaken for the news that Joni Mitchell herself would be here but it figures that someone would want to interpret her as a classic in the way Girl from the North Country, the Lisa McCune musical, reconfigures a batch of the great Dylan songs. How many baby boomers remember the pure uncanniness of when they first heard Joni Mitchell sing? It was a kind of culture shock because the voice was so intensely feminine and at the same time it had a poetic quality that embodied a different worldview that feminism of the Germaine Greer variety only could talk about with great brilliance but which Joni Mitchell could embody with a haunted spectral quality. She was the opposite of the crash or crash through greatness of that powerhouse of a singer Janis Joplin. Joni Mitchell was more like a female version of her fellow Canadian Leonard Cohen but the way she used her womanliness – in the first naked instance her girlishness – was a revelation for some fraction of young men who had never heard desolation and heartbreak (but also female irony) expressed with quite this power of poetic self-possession and as such a challenge to the guy’s eye view of the world.

And what a series of masterpieces the great albums, especially the early ones, were: Ladies of the Canyon, Court and Spark, Blue itself. And they were the definitive expressions of a sensibility that was caressing in the midst of mockery and could see tryhard men coming. ‘You imitate the best / And the rest you memorize / You know the times you impress me most / Are the times when you don’t try / When you don’t even try.’

All this comes across now like the memory of a former life but the great Joni Mitchell songs remain part of the furniture of the mind. She claimed to have looked at both sides now and recalled only the illusions, a young person’s defiance of high hopes. But a line like ‘I could drink a case of you and still be on my feet’ stays in the mind as the definitive expression of a state of mind, a resolution and a moral deliberateness as well as a handy perspective down the decades. It was Aristotle who said the greatest of all gifts was the gift of metaphor.

If Joni Mitchell is one kind of great singer Jonas Kaufman, the great Wagnerian tenor, is a very different one. And it will be a fascination to see him sing the title role in Lohengrin for Opera Australia at Melbourne’s State Theatre on 14 May. Kaufman has a marvellous command of that all but inhuman quality the Wagner tenor roles represent and Lohengrin will be the first time he has appeared here in a full production and it’s good to see this tumultuous drama will have Warwick Fyfe, a notable Australian Wagnerian, as Herald. The production is set in the ruins of immediate post-World War II Germany and it will be amazing to see how this setting consorts with this Arthurian world of swan-drawn boats and heart-lifting wedding marches. Wagner was famously obsessed with the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art, and just as aspects of his musical experimentation made possible Mahler and Shostakovich so his actual drama is full of potential complexities that can accommodate perspectives he could never have been conscious of himself.

They talk of the influence of Schopenhauer on Wagner’s vision in Tristan und Isolde which also has the technical iconoclasm of its counterpoint and chromaticism which invented modern classical music at the stroke of a wand. And that’s a reminder that Stuart Maunder in Adelaide is doing Richard Meale’s Voss, the opera of the Patrick White novel about the Leichhardt-like explorer who has a telepathic relationship with his muse Laura Trevelyan and for which Meale used a very Wagnerian post-Romantic palette in order to dramatise musically a modern novel steeped in the intensities of nineteenth century German Romanticism.

The original production of Voss which comes with a libretto by David Malouf was directed by Jim Sharman – of Jesus Christ Superstar and Rocky Horror Picture Show fame– and was conducted by Stuart Challender with Geoffrey Chard as the agonised quester into the desert and with Marilyn Richardson as his muse. The new partially staged production in Adelaide has Samuel Dundas as Voss and Emma Pearson as Laura with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra and Richard Mills conducting.

Desolation and mystery are at the centre of the new streaming highlight from Binge with Colin Firth and Toni Colette –The Staircase. It in fact takes its bearings from one of the most extraordinary murder trials in American history which was in turn the subject of one of the greatest documentaries ever made and also called The Staircase by the French documentary maker Jean-Xavier de Lestrade. A novelist, Michael Peterson, was accused of killing his wife by pushing her down the stairs and to make things doubly suspicious there had been a comparable incident years before in Germany.

The way in which Jean-Xavier de Lestrade captured the rolling and bewildering toing and froing of a story that involved gay liaisons and the Lord knows what was a wonder in both its first part of the documentary in 2004 and its sequel in 2013. The doco is one of the most remarkable things ever shown on television with the riveting power of real life drama.

The new version of The Staircase is apparently different again because it presents this improbable yet somehow doomed story from the wife’s point of view and this will make for high drama with leads like Firth and Colette and with a story that staggers the mind with its strangeness.

Those who saw the French delineation of an American catastrophe difficult to credit or doubt, a true bewilderment, are unlikely to ever forget the man accused of murder who quotes Romeo and Juliet, ‘All are punishèd.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in