Contemplating a lost position is a bit like having sauce down your shirt. It is annoying in itself, but worse, it often comes with a sting of embarrassment. We chess players are a proud lot, and losing is an affront to our dignity.

And what do your dining companions make of it? You might jokily draw attention to the stain, to pre-empt the suspicion that you hadn’t noticed or didn’t care. It is one thing to be clumsy, but quite another to be thought dopey as well.

The chess player wrestles with a similar urge. A true poker-face is a rarity, and I suspect that is because most of us don’t even try. A vigorous shaking of the head, besides expressing genuine despair, is also an oblique way of saving face. It says ‘Touché! Yes, I am undone, but I know it now!’ Of course, the ultimate ‘mea culpa’ in chess is to resign the game. The act can seem like ripping off a plaster — best done quickly, to minimise the discomfort.

Nonsense! To be convinced of this, one need only see a few examples of games which were resigned when a draw (or even a win) could be achieved by force. Surely a little dour plodding in crummy positions is a price worth paying to avoid that tragedy?

Around 100 cautionary tales have been collected in a slim new book with a title that tickled me: Oops, I Resigned Again (Russell Enterprises, 2021), written by the Australian grandmaster Ian Rogers. This literal catalogue of errors is presented as a collection of puzzles, each recounted with an anecdote that frames the situation through the eyes of the victim.

Rogers cites, as one inspiration, my favourite tactics book from childhood: Blunders and Brilliancies by Ian Mullen and Moe Moss. Most examples were new to me, though a few were familiar, including one recent example in which the former US champion Sam Shankland, playing Black, conceded the game to Anish Giri, in a position that, viewed the right way, was a cast-iron draw. So it was a splendid coup to have Shankland contribute the foreword, rather like having Boris Johnson endorse a book about party planning.

Broadly, there are two types of cock-up here. In most, a player resigns due to a deficit of vision, oblivious to some startling tactical wizardry in the final position. Painful, but forgivable. Far more regrettable are those cases in which the resignation is brought on by an imminent disaster which turns out to be illusory. Sometimes you just have to keep the game going:

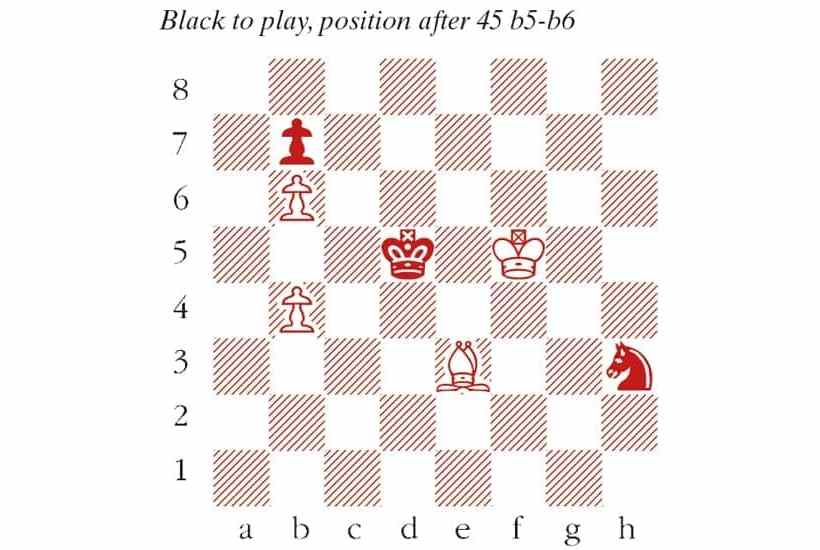

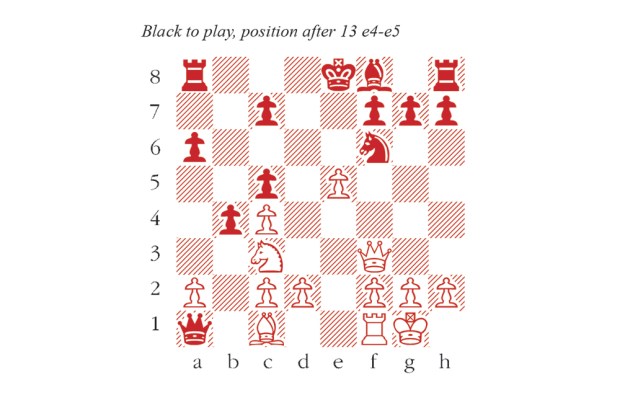

Anish Giri–Sam Shankland

Tata Steel Chess, Wijk aan Zee 2019

Giri has just played 45 b6. Shankland resigned because his knight is trapped, and can be collected soon; 45…Kc4 46 Kg4 Kd3 47 Bc5 offers no respite. But all he had to do was write it off: 45…Kd6, followed by a retreat to c8 achieves an unassailable fortress, quite often found in textbooks. If the Black king reaches a8, any encroachment from the White king produces a stalemate. White may place the bishop on f4 before Kc8-b8 is played, but then Black just plays Kc8-d7 (or d8). In that situation, bringing up the White king still results in a stalemate. Giri, wise to this, made sure to confirm that Shankland’s outstretched hand really was a resignation, rather than a tacit draw offer!

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in