In the summer of 1940, after almost 20 years in Paris, Man Ray fled the Nazis for the country of his birth. Disliking New York, where he’d spent his youth, he made for the West Coast. He hoped to get as far as Tahiti or Hawaii. But his trip came to an end when, braced by the space, lifted by the lack of skyscrapers (‘made me feel taller’) and swept off his feet by a dancing girl (the latest in a long line of hoofers for whom he’d have the hots), he settled in Los Angeles. Though he would live there for more than decade, he never really liked the place.

Nonetheless, he was far more productive in America than in Europe. In his brisk, almost pointillist biography for Yale’s ‘Jewish Lives’ series, Arthur Lubow estimates that Ray’s work rate tripled in America. Not that the work came easy. Ray disliked what everyone else loves about California: the light. He said it was too harsh and sharp. He liked fuzz and blur and spectral glow. He missed the grey shades of his Parisian garret and ordered that the windows of his studio should not be cleaned, the better for the dirt and grime to tone things down a little.

He never aimed for the hard-edged clarity of Dali and Magritte (fellow surrealists determined that their oneiric visions looked like studies of the empirical world). He was after a more feathery or flocculent feel. Both solarisation and Rayography, the two revolutionary darkroom techniques he accidentally invented, go against the grain of the history of photography in that they insist on less, not more, clarity in the finished image. To be sure, Ray’s most famous work, ‘The Gift’, a flatiron with a row of thumbtacks fixed to its soleplate, could be deadly in the wrong hands. Still, if this is a potential weapon, it is one made from something used to soften and smooth out the wrinkles of the world.

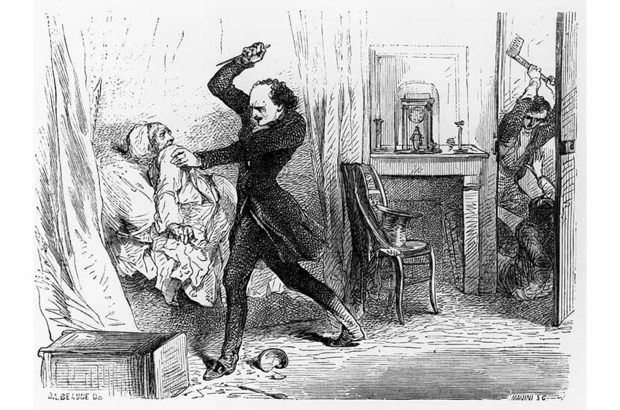

It’s also a near-perfect embodiment of Lautréamont’s famous definition of surrealist beauty as ‘the fortuitous encounter on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella’. Such images were two-a-penny in Rayland: an open valise shadowed by the cluster of coat hangers floating above it; a metronome with a photo of a human eye paper-clipped to its pendulum. Lubow is too literal-minded to make the connection, but what could be more bizarre than the thought of Ray, when he was finally back in Paris after 11 years in the sun, wrapping socks round a lavatory seat the better to warm the surrealist posterior?

What Lubow does keep track of are Ray’s non-stop peregrinations. Barely a page goes by without him upping sticks to another studio, another apartment, another country or another woman. If Lubow leaves you unclear about Ray’s sex life, that’s simply because there was so much of it. The teenage Ray took drawing classes, we are told, only in order to be able to look at ‘a woman in the altogether’. He seems to have spent every subsequent day watching women undress, and I soon lost count of the girls he went to bed with.

For all his jaunting about, he was loyal to the country of his birth. ‘If only America would realise that the art of Europe is finished — dead — and that America is the country of the art of the future,’ he told the New York Tribune in 1915, four decades before the rest of the world caught up. Then again, it was largely due to Ray’s example that American artists were up to speed. His self-portrait with door bells that don’t ring, and his plank that wouldn’t hang straight were first exhibited in 1916, long before Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns stunned the art world with their brollies and brooms and old truck tyres.

A few months earlier, Ray had written an essay in which he argued that ‘the essence of painting is preserved in the flat plane’. It would be 30 years before Clement Greenberg made his name as a critic — and his living as a recipient of gifts from those painters clued up enough to obey his diktats — by claiming that the days of perspectival illusionism were over, and that an artist’s duty was to the flatness of his canvas. Ray, says Lubow, was ‘at least half a century ahead of his time’. Half a century after his death, with an art world that has largely forsaken formal debates for ideological idiocy, he’s still ahead of the pack.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in