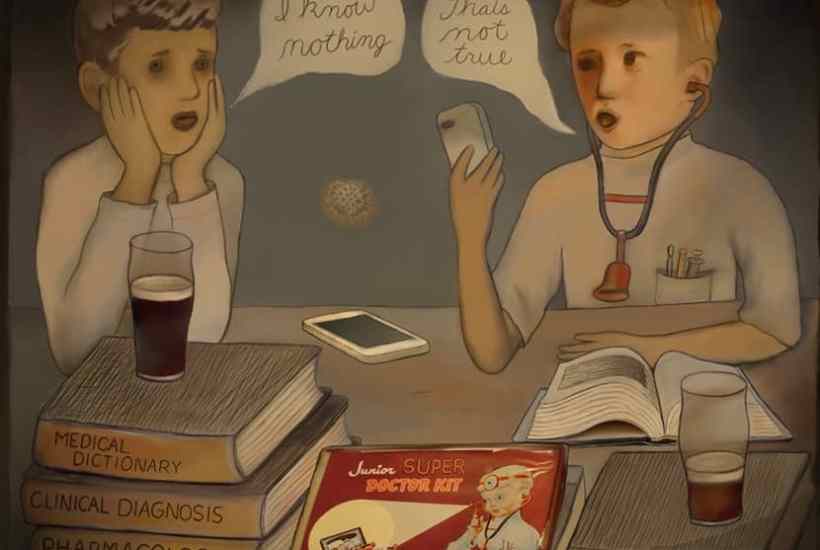

‘I’ve just seen a wen,’ said Gus, returning from the toilets.

‘A what?’

‘A wen. It’s a benign thing, I can’t remember the proper name for it. It looked like a button mushroom growing out of this bloke’s head. Really hard not to stare.’

‘A wen,’ repeated Mark, broodingly. ‘I’ve never even heard of it. How come you know about it and I don’t?’ He mentally added ‘wen’ to his personal 40-volume encyclopedia of medical ignorance.

‘I dunno, I heard it somewhere. Maybe you only know the clinical term.’

‘Unlikely. I’m going to look it up.’ Mark took out his phone and exited the snug; there wasn’t much of a signal in the pub, which was one of the reasons why they went there. Gus resumed reading the chapter on diastolic murmurs in his cardiology textbook. Although he had certainly read it before — after all, someone must have highlighted all those important bits — almost nothing had stayed with him. And yet once his memory had seemed limitless. At Cheadle sixth-form college, he’d been known as BrainMan — also as Total Recall, Deadly Facteria and (by the head teacher, reverently, to anyone visiting the college) ‘Gus, who has a place to study medicine’.

The local freesheet had published a photo of him grinning self-consciously in the college car park, accompanied by the headline ‘GUS SO YOU KNOW, HE’S GOING TO BE A DOCTOR!’ and his grandmother had framed the piece, having first blown it up to A3 on the library photocopier; the vast magnification had disintegrated the outline of his head, so that he looked like a Hubble photograph of one of Jupiter’s less symmetrical moons.

He’d thought, starting at medical school, that he might find London intimidatingly large and the other students patronising in their metropolitan sophistication, and both those things had turned out to be true. What he hadn’t expected was that his class-topping superpowers, the concentration and recall that he had always taken for granted, would evaporate like yesterday’s aftershave.

He’d achieved the thing that he’d set out to achieve, which was to leave Cheadle in triumph, and having achieved it, his will-power had folded its arms and put its feet up. At the end of the first year, he’d scraped a pass.

‘It’s a benign encysted skin tumour of the scalp,’ said Mark, returning to the snug. ‘In other words, a sebaceous cyst.’

He sat down again, and put his head in his hands. ‘I know nothing.’

‘That’s not true,’ said Gus. ‘It’s just not. Last week you spotted the new barman had a Dupeytren’s contracture. And you could spell it. And you knew the treatment options.’

‘Yes, but if he’d also had a wen I would’ve been stuffed. At least you knew a name for it. At least you knew it was benign. For me, it’s just a blank. You’d get just as much information if you asked my dog.’ Mark thought yearningly of his collie Asbo. He had revised for his A-levels sitting next to her on the rug, slowly accruing information, constructing a solid bridge of knowledge, one log at a time. The trouble with this method (and it was the only one he knew) was that, while it had worked well within the narrow syllabus of A-levels, it was now collapsing under the weight of what he was supposed to know, which was (it was becoming apparent) Every-thing. And since he could only ever remember facts that he had painstakingly revised, it meant that if, say, he had got as far as page 72 in Orthopaedic Practice, and his patient’s patellar injury was only described on page 73, then he might as well never have seen a knee before in his entire life. He was unable to extrapolate from existing knowledge — or, as Gus put it: ‘You just can’t bullshit, mate.’

They had met at the beginning of year two, paired on a patient interviewing exercise. Gus had been hoping to be teamed with Alice Trevarrick, whom he’d once snogged at a party, but instead found himself partnered by the small, worried-looking man who always sat in the middle of the front row during lectures. Mark was the same age as him — 20 — but had the air of someone who had been catapulted forward in time from the 1950s. He always carried a briefcase and a plastic box containing homemade sandwiches, and he held his phone to his ear as though it were something slightly dangerous: a small cactus, perhaps. They’d never spoken before, but Gus knew his surname, since it had been just above his on the printed list of students who’d been requested to speak to the sub-dean about consistently low marks.

The patients they were interviewing were all actors, charged with responding in a realistic way, and then reporting back afterwards on the students’ techniques. Gus had got eight out of ten for communication skills (‘very engaging’) and three for accuracy while Mark had been criticised both for his expression of unwavering anxiety (‘I kept expecting him to tell me I had terminal cancer’) and his reliance on the textbook Diagnosis for Medical Students, to which he’d kept referring during the examination.

‘I was concentrating,’ said Mark, afterwards, as they walked back to the lecture theatre. ‘That’s my expression when I’m concentrating.’

‘I haven’t been able to concentrate for about two years,’ said Gus. ‘I’ve tried every-thing — drugs, all-nighters, standing up to revise, going to the library.’

‘I never go to the library,’ said Mark.

‘So where do you revise?’

‘The pub.’

‘You’re kidding.’

Mark shook his head. He couldn’t bear the library because of the crushing weight of the information it contained. ‘You will never read me,’ the books seemed to be whispering. ‘You will never know the things I know.’ And if he tried to work in his room — he was living with his sister, in her house in Herne Hill — there was a kindly-meant but constant pressure, the shrieks and thuds of family life damped by her reiterated hiss: ‘Shut up. Uncle Mark is studying. He is going to be a doctor.’

He had discovered the Half Moon in the course of a long walk, during which he had been listening to a recording of himself reading out the signs and symptoms of liver disease. As a revision technique, it had failed — he would ever afterwards associate ‘Gilbert’s syndrome’ not with enzymatic insufficiency, but with the zebra crossing on Milkwood Road — but just at the point at which he had heard himself say ‘and it is the build-up of bilirubin in the body’s tissues which is the cause of jaundice’, a door had opened in the pub just ahead of him, and a man with jaundice had come out.

They had briefly locked eyes (the man’s sclerae were an extraordinary buttercup yellow) and then the sufferer from excess bilirubin had brushed past him and Mark had found himself walking — as if cosmically reeled — into an enormous bar-room, whose breadth and height and rows of tables were vaguely reminiscent of a library, but a library without books, or silence, or the slightest sign of anyone concentrating on anything at all. An anti-library, in fact.

‘No one takes any notice of you. You can stay for hours,’ he said to Gus.

‘And you can have a drink,’ said Gus. ‘Maybe I should give it a go.’

And so three times a week he would leave his chaotic party-flat in Shepherd’s Bush and take a train to south London. And at their table near the toilets, he and Mark would attempt to study.

They had nothing in common except desperation.

*

‘I’ve had an idea,’ said Gus, coming back from the bar with a Guinness and a lime-and-tonic. ‘Tell me again what a wen is.’

‘A sebaceous cyst of the scalp. Benign, smooth, hairless.’

‘That’s stuck with you, hasn’t it? I mean, that was like a fortnight ago.’

‘I suppose so.’

‘You didn’t have to read it 33 times to remember it, like you do with everything else.’

‘I don’t read things 33 times.’

‘All right, six times or whatever.’

‘12.’

‘12, then.’ Gus took a deep breath; conversations with Mark could be like shifting bags of cement. ‘The thing is, it’s stuck with me as well. It must be something to do with the fact that we saw it somewhere normal — I mean, not in a hospital. So I thought maybe we should do more of it.’

‘More of what?’

‘Diagnosing people in the pub. Every time one of us goes to the bar, we have to spot a pathology, research it, work out a differential diagnosis and then present it. This place is like an alcoholic A&E. In the five minutes I was waiting to be served just now, I saw a woman with a stye, another woman with a weird finger and a bloke with no lobes to his ears.’

‘Lobeless ears aren’t a pathology, they’re just a natural variation.’

‘See — I didn’t know that, I’ve just learned something. So what do you think?’

Mark looked down at the page of pharma-cology that he’d been trying to memorise; his brain felt as if someone had taken a rasp to it. ‘All right,’ he said.

It turned out that the more you looked for clinical signs and symptoms in the Half Moon, the more you saw. Aside from the various visible rashes and protrusions, there were limps and limb deformities, there were respiratory ailments requiring anything from inhalers to a portable oxygen cylinder, there was Bell’s palsy, there were clubbed nails, there was a scaphoid fracture cast worn by a man who also had a keratotic lesion on his ear (‘two for the price of one’ as Gus put it) and there was a wide and florid variety of psychiatric conditions most of which, they reluctantly decided, were beyond the scope of the experiment, since interviewing the patient was out of the question. ‘We can’t really do any of the subtle, empathetic stuff in here,’ Gus said. ‘This is end-of-the-bed diagnosis.’

Of course, the examination had to be fleeting and undetectable — a covert manoeuvre, carried out while purportedly checking change or pretending to look for someone. ‘Guerilla medicine,’ Gus dubbed it. Caught staring once by a man with a crusted mole on the back of his neck and an expression of barely suppressed violence, Mark staved off facial injury by actually stammering out a warning. ‘Because my mother had one like that,’ he lied. ‘They caught it just in time.’

Grudgingly, the man had thanked him, and Mark had returned to the snug not only with a meaty topic for presentation, but a vague recollection of why he had actually wanted to study medicine in the first place. And the extraordinary thing was that the scheme was beginning to work for him. The adrenaline of the exercise seemed to ginger everything up, to move the information about in his head, so that previously unlinked topics formed shaky bonds. ‘I didn’t even know I knew that,’ he said to Gus, one evening, after discussing the concave nails of a woman drinking Campari.

‘I should patent this idea,’ said Gus, who was also beginning to feel the benefits; in the midterm exam he had actually been able to draw upon some solid blocks of knowledge as opposed to a confetti of semi-guesswork. ‘I was talking to Cami about it.’

‘Who’s Cami?’

‘My girlfriend.’

‘Oh.’

‘I’ve only been seeing her a couple of weeks. She’s a first-year medic. Very clever.’

‘Oh.’

‘She wondered if she could come along one evening. I mean, literally one evening, just so she could see what this place is like, because I’ve told her so much about it. We needn’t even do our usual presentations.’

‘What would we do, then?’

‘Well we could — er…’ He’d been going to say ‘…just talk and have a drink’, but it was obvious from Mark’s expression that this wouldn’t go down well. ‘Well, what if we did something a bit different? I don’t know — a quiz or something. A pub diagnosis Christmas special.’

Mark looked at him unhappily. This was seismic.

‘I could ask Cami to bring a friend,’ said Gus, widening the fissure. It occurred to him that he had no idea what sort of friend Mark might prefer. ‘Or friends,’ he added. ‘It would just be a break. We could go back to the usual in January. I mean, everybody needs a change now and again, don’t they?’

Mark didn’t. This idea that ‘everybody needs a change now and again’ was one of those sayings you were supposed to automatically agree with, but which, in practice, seemed to operate on an unfairly sliding scale. So for someone like Gus the word ‘change’ translated as ‘carry on shagging and drugging and partying as usual but in a slightly different geographical location’, while for someone like himself it meant ‘why not completely alter the things that make your life tolerable?’. In the end, it was his sister who made up his mind for him: ‘Can you babysit on Friday?’ she asked. ‘Or are you meeting up with your friend as usual?’

*

At the Half Moon, he stood hesitating outside for five minutes. It was a cold, clear night, ice already beginning to form on a nearby pool of vomit. The roar from the bar seemed louder than usual.

‘Oh great, you’ve come,’ said Gus, cheerfully. ‘Didn’t know if you would. This is Cami, and Chloe and Petros.’

‘Yes, hello,’ said Mark, lifting his hand in a gesture reminiscent of an earthman greeting aliens. They were all Gus’s sort of people: laid-back and slightly drunk. Two of them had piercings.

‘Busy, isn’t it?’ said Gus. ‘I think it’s someone’s birthday. Anyway, perfect for tonight — we don’t have to move, the patients will come to us!’

People were shuttling in both directions past their table; some were wearing party hats.

‘This is an amazing place,’ said Cami, lowering her voice to a whisper. ‘We’ve already seen someone with Bell’s palsy.’

‘He’s a regular,’ said Mark, feeling suddenly proprietorial. ‘I presented him last week.’

‘OK,’ said Gus. ‘Let’s get started — here’s yours.’

He passed Mark a hand-drawn card divided into squares, some blank, some with writing. Mark stared at it suspiciously. ‘What’s this?’

‘It’s a genius-level idea I had yesterday — medical bingo. Instead of numbers, there are clinical categories. If you see someone with a diagnosis in one of the categories, stick your hand up. If you’re right, you cross it off. First one to get a line wins this’ — he waggled a grotesquely huge bar of chocolate — ‘and first one to finish their card wins this.’ He held up gold badge, with the word SUPERDOC printed on it.

‘It’s not really fair, though, Gus,’ said Chloe, who kept pushing her hair around, as if she couldn’t decide which ear to keep warm. ‘I mean, I’ve only done a term, I don’t know anything yet.’

‘Well why don’t you team up with Petros? He’s a third-year.’

‘And I can be with you,’ said Cami, nudging Gus. ‘And Mark, you can be a team of your own, because Gus says you’re a human hard drive.’

Mark had been getting a pen out of his briefcase, but he halted, one hand curled in mid-air, his expression fixed, as if he’d just been put on pause.

‘Compared to me,’ said Gus, realising that something was wrong and scrabbling for the right remark. ‘I meant, compared to me. I wasn’t — you know — comparing you to a — I just meant that when you learn stuff, it sticks. That’s what I meant. Didn’t I, Cami?’

‘Yes, that’s what he meant, I think,’ said Cami, confused.

Mark nodded, rather stiffly. So, they’d been laughing about him. That was, of course, something he was used to; at school, he’d lived with the constant knowledge that he was a topic of amused discussion — had achieved, in fact, a sort of local fame (‘Here comes briefcase man!’). Which was ironic since all he’d ever wanted to do was to get quietly on with things, unnoticed and unnoticeable. At university, on a crowded course in a crowded city, it had been easier to disappear. And when the Half Moon revision nights had started, he had somehow thought that the sessions existed in a sort of bubble, unconnected with the rest of the world: ‘The first rule of Blight Pub is that you do not talk about Blight Pub’, as Gus had put it one evening, but clearly that was not the case.

He clicked his four-colour biro to red, and placed it beside the bingo card.

‘Shall we start then?’ he asked.

Gus nodded, subdued. The party atmosphere round the table had collapsed, leaving a little pocket of silent discomfort in the midst of genial uproar. From the bar, a multi-keyed chorus of ‘Happy birthday, dear Lennnneeeeeee’ was audible.

‘All right,’ said Gus. ‘Eyes down. Or up, I suppose. Raise your hands as soon as you see a category on the card and — you know — keep your voices down.’

Mark raised his hand. ‘Orthopaedic, lower half.’

‘Where?’ asked Chloe.

‘The man with the denim jacket who just went into the gents. Foot drop.’

Chloe frowned. ‘I didn’t see anything wrong with him.’

‘It’s barely noticeable. You’d have to really look.’

Mark put a cross through ORTHOPAEDIC, LOWER HALF on his card, briefly scanned the passing crowd and then raised his hand again. ‘Dermatology, hands. Woman with the red hair had psoriasis on her knuckles.’

‘Hang on,’ said Gus, craning after her. ‘I don’t think it was even visible tonight.’

Mark was already crossing off DERMATOLOGY, HANDS.

‘You mean you already know what all these people have wrong with them?’ asked Chloe.

‘Yes. Most are in here every night.’

‘Well, the rest of us don’t stand a chance, do we?’

Mark raised his hand again. ‘Metabolic. Man with facial pigmentation indicative of haemochromatosis. Which means I’ve got a line.’ He held out his hand for chocolate.

‘This is ridiculous,’ said Chloe. She pushed back her chair. ‘I’m going out for a cigarette. You coming, Cami?’ Petros followed them.

Mark sat very upright, clicking and unclicking his biro, his eyes flicking across the passing crowd.

‘Why are you being such an arse?’ said Gus. ‘What’s wrong with you?’

‘I’m a human hard drive.’

‘Oh fuck.’ Gus rubbed his forehead. ‘It was just a remark. I wasn’t diagnosing you.’

‘I don’t like people talking about me.

I don’t like being made fun of.’

‘I wasn’t making fun of you. Christ! There’s a whole series of gradations between not talking about someone at all and taking the piss out of them. You need to get out more.’

‘I already get out three times a week, don’t I?’

‘What, here you mean? But this is work, it’s not… it’s not a social life, it’s not like going out with friends.’

Mark’s head snapped back as if he’d been slapped. No, thought Gus, I drove down the wrong road there, I shouldn’t have said that. And in any case, it wasn’t entirely true — over the weeks, their meetings had acquired an oddly comfortable rhythm. ‘I mean, it’s obviously sort of social,’ he said, attempting a reverse. ‘It’s just that it’s not…’

‘Can we finish this?’ Mark’s face was taut.

‘Finish what?’

‘The bingo game.’

‘What? No.’

‘Just the last four categories — I’ll waive the ones I’ve already done. I only came here because you said there’d be a quiz, I don’t want to waste the evening. I could be at home, now, studying.’ Babysitting.

Gus looked around. There was no sign of the others. From the table top, the SUPERDOC badge glinted temptingly.

A near-dormant competitiveness stirred in him — a throwback to his years at the top of the class.

‘Oh all right. Just till they come back. But we’re only allowed to nominate patients we’ve never seen before.’

They sat in strained silence, watching the human traffic. The man with the Bell’s palsy passed by them again, followed by the man with foot drop. A group of girls had an intense and whispered conversation before shrieking back to the bar.

Gus raised a hand. ‘Genetic anomaly. The girl in green had no earlobes.’

‘It’s a natural variant.’

‘Oh yes, I forgot… I didn’t press “save” obviously.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘That’s my own computer analogy. I’m just a screenful of temporary documents. Cami’s Wikipedia. Chloe’s a pop-up, always following Cami around — very annoying.’

Mark gave him a slight glance. ‘What about Petros?’

Gus shrugged. ‘I don’t know anything about him.’

There was a pause. ‘Zipped file,’ said Mark.

Gus actually laughed. ‘See,’ he said. ‘This is what people do. They talk about other people.’

‘Yes, but some people get talked about more than others.’

‘Well obviously. Obviously. There are always going to be natural variants.’

Mark blinked a couple of times, absorbing this. ‘I read that the absence of earlobes, wisdom teeth and appendices are becoming more common,’ he said, ‘because there’s no continuing evolutionary reason for their presence. The human body’s moved on.’

‘Right.’ Gus nodded. ‘So what you’re saying is, you’re actually more evolved than the rest of us.’

Mark didn’t meet his gaze, but the corners of his mouth moved slightly. ‘Possibly,’ he said.

They were silent for a bit longer, but it was an easier silence.

‘You know, we’ll never get all these,’ said Gus, waving his card, ‘I might as well go to the bar’ — and as he spoke, as he started to rise, there was a break in the crowd. ‘Make way for the birthday boy!’ called someone, and a wheelchair nosed into view, pushed by a large man in a short-sleeved shirt. Mark stiffened like a pointer, and grabbed his biro. The wheelchair occupant, an elderly man, was wearing a cardboard crown with the word ‘Lenny’ on the front, and was tremendously and happily drunk. He was also clinical gold dust.

‘Talipes. Congenital anomaly,’ said Mark, barely moving his lips.

‘Scoliosis,’ muttered Gus, putting a cross through ORTHOPAEDIC, SPINE.

‘Metabolic disease,’ said Mark. ‘Thy—’

‘—roidectomy scar,’ finished Gus.

They glanced down at their cards.

DERMATOLOGY, NECK AND ABOVE was still for the taking.

They looked up again. The wheelchair was almost past, only the back of the occupant’s head visible, but at the centre of it, framed by the cardboard crown, was something smooth, hairless and dome-like. A wen.

*

‘What the hell?’ asked Cami.

‘I’m okay, I’m okay.’ Gus straightened his jacket; the collar had almost been torn off by the larger of the two barmen. ‘Let’s just walk.’

‘You’ve been thrown out of the pub?’ She glanced back to the entrance, where an interested crowd was still standing.

‘Yes. Barred, in fact. You all right, Mark?’

‘I dropped the chocolate.’

‘Least of our problems. Is my ear bleeding?’

‘No. What about my neck?’

Gus inspected it. ‘You’ve got a scratch there, yes.’

‘We’ve only been away five minutes,’ said Chloe. ‘What the fuck did you do in there?’

‘Bit of a disaster. The landlord thought we were taking the piss out of his disabled uncle.’

‘What?’

‘We weren’t doing that, obviously we weren’t, but — you know — it looked bad. We drew attention to ourselves. We handled it badly. The whole bingo thing was a disaster.’

‘We shouldn’t have shouted “House”,’ said Mark.

‘Yes, the main thing is, we shouldn’t have shouted “House”.’ Gus let out a sudden, inadvertent neigh of laughter. ‘Sorry, post-traumatic,’ he said, rubbing his ear.

Mark was conducting a self-examination: pulse 160 a minute, respirations 20, mouth dry, hands shaking slightly, eyes feeling as if they were dancing around on stalks.

‘You sure you’re all right, Mark?’ asked Cami.

‘Adrenaline burst,’ he said.

‘We’re probably going to Willesden for a party. Do you want to come?’

He shook his head. ‘I’ll go back and put some antiseptic on this scratch.’

‘And on your way, keep a lookout for another pub,’ said Gus. ‘We’re going to need somewhere else to revise.’

*

Mark walked quickly, the freezing air already beginning to crisp the sweat on his neck. He had, he knew, behaved in a way which could deservedly have had him flung out of medical school. He had been threatened with both violence and the police. He had been hauled through a gaping crowd by a man with biceps like bolsters. He had shocked people who possessed multiple piercings. He felt absolutely and extraordinarily magnificent. Pausing at the foot of Denmark Hill, he took the SUPERDOC badge out of his pocket and pinned it on.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in