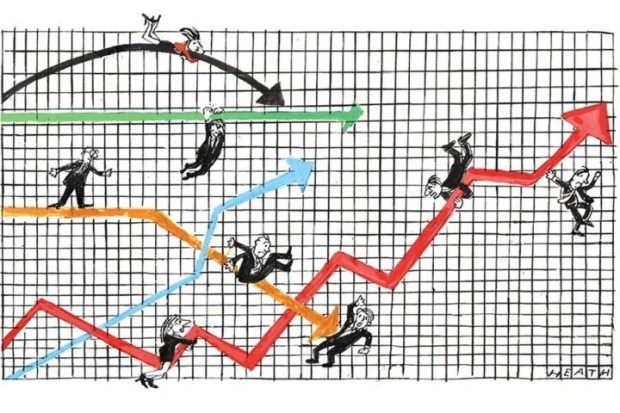

The big central banks have been insisting for months now that the rise in inflation is temporary, and will fade once the great awakening of the world economy starts to settle down. The Federal Reserve, Bank of England and the European Central Bank have looked on as inflation has overshot their forecasts. But when the opportunity to tame it with an interest rate hike approaches, the banks pass it up, reiterating instead that it is ‘transitory’ — the monetary equivalent of ‘it’ll be fine’.

With inflation now at a 30-year high in the United States — 6.2 per cent — it’s starting to look like a pretty big bump. But should we worry? Is this just a glitch of lockdown unwinding itself? As Ross Clark points out on Coffee House, inflation is being witnessed across all sectors of the economy in the US. It’s not just in hospitality, which is still waking up after 18 months in hibernation. Nor in energy prices, up 30 per cent over the year. Fewer flights mean less competition and higher airfares. We see it in food, housing costs and cars, too.

The BoE now isn’t even pretending this will soon be under control. Its own forecasts show inflation peaking at around 4.5 per cent next year (with the acceptance in recent weeks that it may climb to 5 per cent), which will be more than double the Bank’s 2 per cent target. Meanwhile, with the year nearing an end, tight labour markets and supply chains will be problems that expand well into 2022.

In the best case scenario, where the effects of shutting down the global economy and then kick-starting it again fade in the new year, ‘transitory’ will still have come to be defined as an 18-month period, during which the cost of living significantly rose and increases to pay packages were wiped out by higher price tags on goods and services. But under an increasingly likely scenario, the definition of ‘temporary’ loses all meaning, as rising inflation continues to take its toll — not just on the consumers, but on government finances as well.

If central banks do hike interest rates — even modestly compared with historical levels — it’s going to create difficult situations across the west for countries that have adopted borrowing policies on the idea that amenable conditions to print and spend huge amounts of money wouldn’t change. If inflation and rates rise, even by 1 per cent across the board, where might Rishi Sunak find the £20 billion plus to cover servicing the debt?

It’s not obvious he can rely on growth to cover the costs, despite positive forecasts that the UK is set to outpace the other G7 countries on the path to recovery. September’s growth figures, released this week, are good news on the face of it: the economy grew by 0.6 per cent, slightly better than market consensus. But figures for July and August were downgraded – to -0.2 percent and 0.2 per cent respectively – while overall growth in Q3 only reached 1.3 per cent. Not only does this mean the UK has still failed to return to pre-pandemic levels, but it suggests that the period of rapid recovery is long over. It’s now a process of inching upward, which does not bode especially well for all the other pressures the economy must withstand.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in