When maverick ex-New York Times reporter Alex Berenson said that the Covid-19 jabs didn’t stop infection or transmission, and were best thought of as therapeutics, Twitter booted him. ‘Misleading,’ Twitter said. But if you follow the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s evolving definition of what a vaccination is, Berenson seems to be right in tune.

This month the CDC abandoned its definition of vaccination as providing ‘immunity’ to a disease and opted instead for the much weaker ‘protection’. It is hardly cynical to wonder at the timing of this change, since the first vaccine – still described as granting immunity – was against smallpox over 200 years ago.

Referring to the CDC as the ‘Ministry of Truth’, GOP congressman Thomas Massie highlighted on Twitter three different CDC vaccination definitions used over the past decade, outlining the gradual weakening of the terminology. Pre-2015 it was ‘an injection… to prevent the disease’; from 2015-2021 it was ‘to produce immunity to a specific disease’; and from September 2021 it is ‘to produce protection from a specific disease’.

This looks a lot like fitting the definition to the Covid jabs’ limitations. Highly-vaxxed Israel shows us the jabs prevent neither infection nor transmission of the disease, nor do they prevent death. They do however reduce Covid’s severity, at least for some months, boosters having now been prescribed. In the CDC’s defence a spokesman said previous definitions could have been understood to mean ‘100 per cent effective, which has never been the case for any vaccine’.

Lexicographers elsewhere, however, seem to be laboring under similar delusions to Berenson’s as to whether vaccines prevent disease. Google offers (as of 12 September) ‘treatment with a vaccine to produce immunity against a disease’; Wikipedia opts for ‘active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease’. Britannica: ‘primarily to prevent disease’. Collins: ‘to prevent getting that disease’. The result is that a respected word and concept, gilded with the lustre of historical success against smallpox, polio and many more, is now being used to promote pharmaceuticals that do not, so far, reach the same heights.

Like Orwell’s Newspeak in 1984 and Lewis Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty, for whom a word means ‘just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less’, this is language adapted not in the service of clarity or communication, but of ideology.

There is nothing new in that, unfortunately. Words are weapons, and have always been used by those in power to buttress their status and beat back dissent and challenges. Now with the pandemic, there is a full court press in the media to get the jabs into everyone as the sole route out of lockdowns and illness. Forget any public discussion of alternative treatments, be they vitamins/zinc/ivermectin/hydroxychloroquine/monoclonal antibodies, or anti-obesity measures or whatever else your doctor wants to prescribe for you. Forget any discussion of vaccine-adverse events, because it might boost ‘hesitancy’. Headlines scream the ages of Covid victims when they are young, to frighten you into thinking you are in danger and must get jabbed, although it is mostly the elderly who are dying.

Nor do we get the context of how many are dying of other diseases, many far above the Covid toll. And if a few words need to be changed to promote the good of the community, then apparently, that is what we must do.

Words transmit ideas and knowledge, and controlling ideas and knowledge has been the aim of elites of all eras. I have recently been schooled in the history and achievements of Judeo-Christian culture by a Hindu philosopher, Vishal Mangalwadi, whose work The Book That Made Your World, provides an eye-opening outsider’s view on why the West is as it is. He gives a potted history of the millennia-long battle by religious, military, political and aristocratic elites to withhold and monopolise knowledge of the Christian scriptures, then written in the Latin Vulgate. He writes: ‘One way to keep government of the rulers, for the rulers and by the rulers is to run it in a language not understood by the ruled’. In England in the late 14th century anyone found in unlicensed possession of scripture in English faced the death penalty.

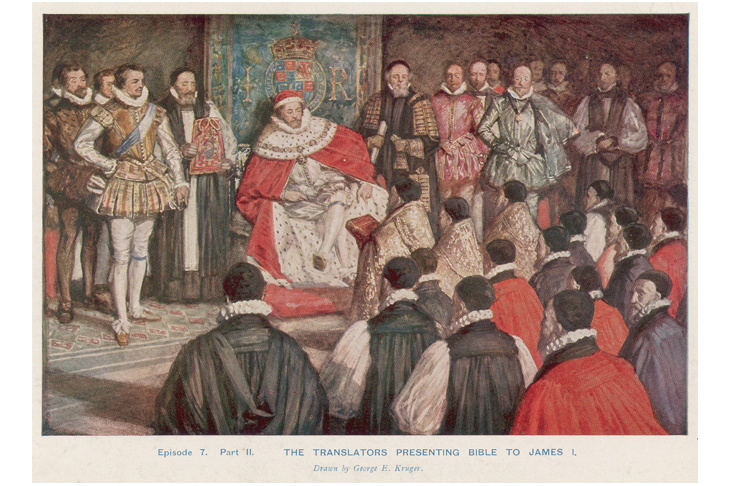

Keeping the sacred texts in Latin, Greek and Hebrew and forbidding translations into vernacular English made religious knowledge a virtual secret cult, entrenching church self-interest but also ignorance. In Gloucestershire in 1551, a reforming bishop noted of his ‘unsatisfactory clergy’ that nine did not know how many Commandments there were. Scholar William Tyndale fled England to translate the Bible into English, for which act of rebellion he was executed in 1536. Mangalwadi argues that the subsequent Geneva Bible, and then the King James Bible brought the truth of Christianity to all and propelled the subsequent blossoming and world-changing rise of European Judeo-Christian culture.

(An aside: Just as studying another language offers fresh insights into one’s mother tongue, so a cultural outsider notices differences hidden to cultural natives. Take education. Mangalwadi said he was surprised to discover that it was British clergy who had stitched together local dialects to create both Hindi and Urdu, now the national languages of India and Pakistan, because unlike Muslim and Hindu rulers, they valued education for all people, not just select groups.)

Here’s a final example of how words can act as cultural signifiers. For my sins I sat through a rugby league final on the Sunshine Coast recently, which included the obligatory Welcome to Country. I was offended to note that there was no corresponding National Anthem. If we are going to honour one culture and group of people, at least acknowledge the existence of the rest of us. Otherwise we risk elevating one group over the other. Words matter; use with care.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in